Mother Jones illustration; Jacquelyn Martin/AP; Getty

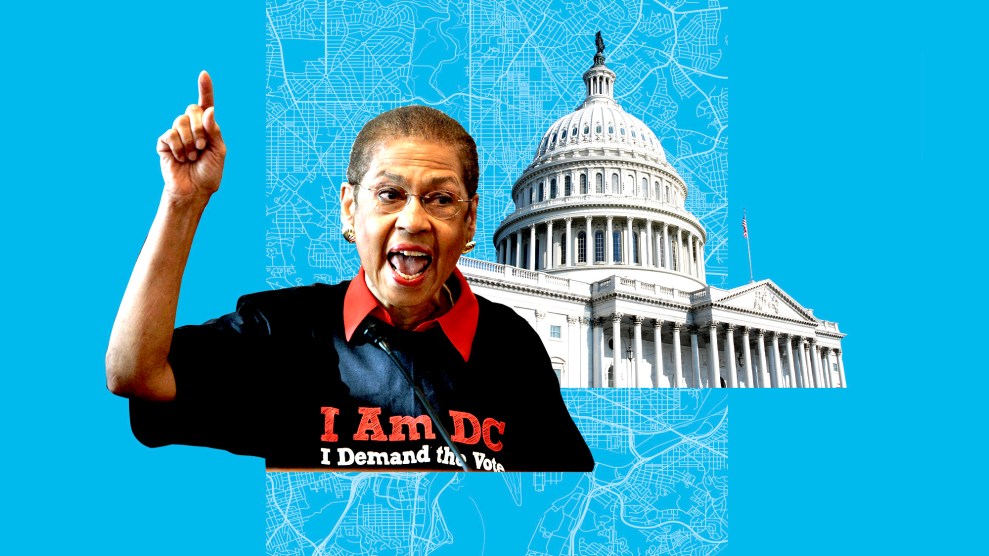

There’s a rectangular patchwork quilt that hangs above the doorway leading into US Del. Eleanor Holmes Norton’s office that’s easy to miss. It overlooks the doorway into the busy walls in the waiting room of her congressional office—walls littered with various framed mementos from her long career as the lone, non-voting delegate representing Washington, DC. The “non-voting” descriptor is obvious throughout her office: nearly every memento is a not-so-subtle reminder of the District of Columbia’s 231-year struggle for equal rights and representation. A framed Washington Post poll from 2007 on support for statehood sits above a 2011 mailer from the DC statehood advocacy group DC Vote warning Congress not to tread on District affairs. Even the patchwork quilt, frayed at the edges and showing its age, dons Norton’s de facto office mantra: “STATEHOOD 4 DC NOW.”

The quilt, each square its own funky pattern of loud textures and cool earth tones, is so old Norton, 83-years-old herself, can’t remember when she got it. “It’s been years,” she says with a chuckle. “Someone just made that for me, and I said, ‘I gotta find someplace to hang that.’” The sentimentality and the bold but worn patterns reflect the tenacity and, sometimes, tedium of her career: For three decades, she’s haunted the halls of Congress as the District’s sole delegate, only the third person to ever hold the position. She’s spent those years not just as a tireless advocate for the District but often a thorn in the side of any member of Congress who dared to meddle in DC’s affairs, like when Maryland’s Republican Rep. Andy Harris waged a war to challenge DC’s marijuana decriminalization law. “If he wants a free ride—a free propaganda ride, a free messaging ride—on the backs of African American youth in my city, well, he’s going to hear from me,” she fired back at Harris in 2014. She’s the national face of DC statehood, partially thanks to her frequent appearances on The Colbert Report as the faux nemesis of Stephen Colbert’s smarmy Conservative idiot character, where he once joked that her position in Congress has “less power than a student body president.”

Her decades-long work may finally be paying off. In early January, she yet again introduced her bill to grant statehood to the District of Columbia—something she has done for each of the past 14 sessions of Congress—except this time it came with 202 cosponsors and a Democrat in the White House who would sign the bill. After several sessions of spirited debate on the House floor, it passed in late April with universal support from House Democrats. It’s expected to eventually get a full hearing and floor vote in the Senate—the farthest a DC statehood bill has ever gotten. Whether it will actually pass that floor vote, though, is a different question altogether, as not even all 50 Democrats in the Senate have said they’d support it—let alone the additional 10 Republicans that would be required to overcome a filibuster.

Still, for Norton to have gotten this far—despite decades of bad-faith opposition from Republicans and hollow gestures of support from fellow Democrats—is no small feat. Fifty-four percent of American voters support DC statehood according to a recent poll, and Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) and President Joe Biden have both issued full-throated support. “The kind of support we have now is unparalleled,” Norton says with the utmost confidence.

Which is why I found her comments to the Atlantic earlier this winter so surprising, as she urged Joe Biden to not push statehood for the District. “If he jumps DC statehood ahead of the two or three issues that have priority, people will think he’s crazy,” she said. “We’re not ready to have him jump the issue on DC statehood yet. We have to do more homework in the Senate.” After reaching a pinnacle moment, Norton is playing a careful game that might backfire: championing the progress made, but cautioning her constituents to be patient until 2022, when she’s certain Democrats will gain a larger majority and finally have the will to act. But it’s the Democratic Party’s inability to forcefully fight to boost representation—while Republicans use their power in state houses to roll back voting rights—that just might doom Norton’s cause for at least a decade or more.

Born Eleanor K. Holmes in Washington, DC in 1937, her mother was a school teacher and her father a civil servant. While attending Antioch College and grad and law school at Yale University, Norton was active in the civil rights movement and worked as an organizer for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. She was an integral part of Mississippi Freedom Summer and worked closely with Medgar Evers, the renowned civil rights activist. After graduating from law school in 1964, she briefly clerked for Federal District Court Judge A. Leon Higginbotham, Jr before going to work at the American Civil Liberties Union as an assistant legal director.

Norton’s first big legal win came in 1970, when she represented 60 women who worked at Newsweek who spoke out against the magazine’s policy of only allowing men to be reporters. She won the case and the magazine changed its policy. Shortly after that case, New York City Mayor John Lindsay appointed her as the head of the NYC Human Rights Commission in 1970, where she held the country’s first hearings on discrimination against women. In 1977, President Jimmy Carter appointed her to chair the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, where she wrote the commission’s first guidelines on sexual harassment in the work place that declared that harassment was a form of sexual discrimination and violated federal civil rights laws.

Del. Eleanor Holmes Norton in February, 1993.

Laura Patterson/CQ Roll Call / AP

After she left her White House job, Norton stuck around her DC as a professor at Georgetown University Law Center. During that time she was a vocal anti-apartheid in South Africa activist and co-founded the Free South African movement with a 1984 sit-in at the South Afican Embassy. But the suppression of rights in her hometown was always at the front of her mind. “We’re in 220 years of trying to get equality with the rest of America,” Norton says. “I’m a third generation Washingtonian. That means nobody on my father’s side of my family has ever experienced equality living here in the District of Columbia.”

When she first came to Congress in 1991 she immediately got to work on a DC statehood bill in the House. But even with a Democrat-controlled House, in 1993 her bill was overwhelmingly voted down 277 to 153, with 40 percent of House Democrats voting against the measure, along with all but one Republican. “That vote did not prevail because Democrats then were divided between Southern Democrats, who eventually became Republicans, and the rest of us,” Norton says. At the time, statehood was such an unrealistic possibility that to merely get a floor vote, even if it was soundly rejected, was nonetheless spun as a win, a necessary first step before eventual success. “I’m ready to declare victory right now,” Norton said at the time. “This vote has surpassed my greatest expectations.”

But any forward momentum disappeared as Democrats lost control of Congress in 1994 and wouldn’t regain the chamber until the last two years of the Bush administration, in 2007. For more than 20 years following the 1993 floor vote, there wasn’t even a congressional hearing on DC statehood, despite the fact that Norton continued to introduce her bill in every new Congress. In September 2014, a few months after then-President Barack Obama officially endorsed statehood for DC, the Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs held a hearing about creating a new state out of DC—the first since the 1993 vote. But it never got further than that since it stood no chance in the Republican-controlled House. “Unfortunately, for most of my time in the Congress, I have been in the minority,” Norton says.

The case for DC statehood is not hard to parse. More than 700,000 people live in the District—a population larger than Vermont and Wyoming—but it doesn’t have the same representation in Congress. And that disenfranchisement predominantly affects people of color—DC has historically been a majority Black city. Beyond congressional representation, the city lacks the same authority as other local governments across the country. The federal government has control over some of DC’s municipal affairs thanks to the Home Rule Act of 1973, which gives Congress the authority to block any laws passed by the DC council. That issue has only come up a handful of times—most notably in 1988 and 2011 when Congress voted to block the District from using local funds to cover abortion services, and again in 2014 when DC voters overwhelmingly voted in favor of a ballot initiative to legalize marijuana.

“The years of work done by Congresswoman Norton, on the inside of the Congress, as well as the work done by us and other organizations on the outside have brought us to where we are now,” says Bo Shuff, the executive director of the statehood advocacy nonprofit DC Vote.

While Norton has worked to keep the issue alive in Congress, statehood has gotten a bigger national boost in recent years thanks to a new generation of young activists. Groups like Shuff’s DC Vote have long run campaigns to make people outside of the Beltway more aware of Washingtonian’s plights. But 51 for 51—another statehood advocacy group founded in 2019 with the backing of national policy groups like Indivisible and Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence—helped push the issue further into the national sphere through a grassroots campaigning effort that had members traveling all over the country to speak with voters who were ignorant to the District’s plight. Of course, the city’s changing demographics over the past decade—what was once Chocolate City has become more vanilla as white transplants have flocked to the District over the past decade, at the cost of its once majority Black population—has also helped the statehood movement gain momentum. As more transplants move into DC, they become aware of the District’s unique, disempowered status as a city whose residents pay the same in federal taxes yet don’t get a vote in Congress.

But like most moral and legal issues these days, partisan politics have completely swallowed the debate. For the Republican Party, statehood is a line in the sand. The District’s registered voters are mostly Democrats—more than 92 percent of DC voters chose Joe Biden last year—meaning that statehood for DC would likely equal two extra Senate seats for Democrats. Of course, no Republican will admit that that’s the reason for the opposition. Instead, they have spent countless hours of debate in a pair of House hearings arguing that DC shouldn’t be a state for a variety of silly reasons, like its lack of car dealerships or surplus of political yard signs, though chief among them that it is unconstitutional—an argument that holds little weight, especially after dozens of constitutional scholars sent a letter to Congress saying that it is, in essence, a nonsense excuse.

These arguments, at least on the House floor, have provoked the otherwise collected and even-keeled Norton to sometimes lose her cool. In one of the recent House debates on statehood, Norton had to scream at Rep. Guy Reschenthaler (R-Penn.) to shut up for continuously interrupting her with illogical arguments. But she admits what happens on the House floor, stays there. “Well we don’t have a good-faith conversation in those hearings,” she says. “Off the floor, we’re quite friendly. But, you know, don’t mess with me during debate here.”

There is currently one thing standing in the way of DC statehood, and it’s not just Mitch McConnell and the 60-vote threshold of the filibuster. West Virginia Sen. Joe Manchin, who Norton likens to the Southern Democrats in 1993 who opposed statehood in that first House vote, has firmly planted his feet against it, while a few other Democratic senators have been conspicuously silent on the issue. Still, the Senate bill has a record number of co-sponsors and the Biden administration has enthusiastically endorsed the movement—something that his predecessor, Obama, only tepidly supported, to Norton’s disappointment. “It wasn’t enough,” she says with an exasperated sigh. “He supported statehood, but we didn’t get the kind of support for statehood that we’ve gotten from President Biden.”

If you ask Norton how, exactly, the Democrats plan on abolishing the filibuster, she explains it with a confidence as if it has already happened: First, the Democrats are going to expand their majority in the House and Senate in the 2022 midterms. Then they’re going to vote to abolish the filibuster. And then the DC statehood bill will promptly pass and be signed by the president. “That’s why the Senate was given to the Democrats,” in the last election, she says. “Let’s see what they can do with it. If they manage to move anything ahead, they’ll have to get rid of the filibuster. And if they get rid of the filibuster, we’re on our way to statehood.” She adds that, given that the Republican Party continues to endorse Donald Trump’s Big Lie—that the 2020 election was stolen through unparalleled and completely unproven voter fraud—there’s no way they’re going to win any seats in 2022 and will, in fact, lose some competitive races.

But all that is riding on Senate Democrats and their ability to use their slight majority to their benefit—especially when it comes to voting rights, including statehood. The filibuster’s 60-vote threshold is preventing Democrats from passing many of their big-ticket items—including the For the People Act, an omnibus voting rights bill that would protect states from the myriad voter suppression laws that state Republicans are currently pushing through in places like Georgia, Pennsylvania, and Arizona. With redistricting on the horizon, there’s a lot riding on the 2022 midterms, especially considering that these voter restriction laws passed on the state level, along with gerrymandering, are teeing Republicans up to possibly regain control of Congress. “Congress has the power—and the responsibility—to ensure every American can participate in our democracy without jumping through ridiculous hoops intended to block their votes,” Michael Waldmen, the president of the public policy think tank the Brennan Center, recently wrote.

Right now, what’s standing in the way of Congress protecting voting rights for millions of people across the country is the same obstacle standing in the way of statehood: Manchin, the West Virginia Senator, and a handful of other Democrats unready to ditch the filibuster. Unless Manchin can be flipped on both the filibuster and statehood, the future of DC rests squarely on the unforeseeable outcome of the 2022 midterms—which might not go the way Norton thinks it will.

But she refuses to accept that alternative. She believes that country has had big shift in the past few years—in spite of, or perhaps because of, Trump, a shift that has set it on a crash course for DC statehood. “This is a country now that’s had Black Lives Matter, we’ve had people to take down Confederate monuments,” she explains. “There’s a real pro-democracy movement that’s been going on in this country now for at least four or five years. And DC is swept up in that.”