<a href="http://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/ppmsca.27897/">Library of Congress</a>

The farm bill—that vast, byzantine, twice-a-decade plan for federal food, ag, and hunger policy—expires on Sept. 30, just weeks before what promises to be an epically contested presidential election.

Under normal circumstances, getting Congress to agree on such complex and expensive legislation at a politically charged juncture would be daunting. This year, with both parties touting fiscal austerity and with the GOP-dominated House having recently approved a draconian budget proposal, getting a farm bill through the legislative process will be nearly impossible.

But none of that will likely stop Big Agribusiness from getting what it wants, which is programs that underwrite environmentally ruinous, nutritionally vapid corn/soy agriculture. Take Big Ag’s lobbying power and add a big pinch of fiscal hysteria and what you get is thin gruel for everything else in the farm bill, which could could choke off the USDA’s progressive-ag programs and even result in sharp cuts to hunger programs at a time of high un- and underemployment.

That’s the assessment I recently got from Ferd Hoefner, the policy director of the Washington-based National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition and a veteran of farm bill fights starting in the ’70s. Hoefner added that, despite the uncertainty on when the bill will actually be passed, we’ll likely see its broad outlines take shape in the near future.

The Senate Agriculture Committee is currently cobbling together its farm bill proposal, Hoefner says. “What happens in the next four weeks [in the Sentate Ag committee] will largely determine what’s going to happen in this farm bill, regardless of whether it finishes this year,” he said. That’s because the Senate version will represent what Hoefner calls the bill’s “high water mark” in terms of progressive policy. When the Senate bill goes to the the budget-slashing House for reconciliation—whenever that reconciliation actually takes place—it will likely be pushed in more regressive, Big Ag-friendly directions.

Hoefner broke down the key issues for me one by one.

• Progressive food and ag programs on the chopping block. For decades, groups like Hoefner’s have worked hard to create a set of programs designed to at least partially offset US farm policy’s tendency to bolster Big Ag. The programs, which the Obama Administration in 2009 grouped under the banner of Know Your Farmer, Know Your Food, include initiatives designed to assist new farmers to get loans help communities roll out farmers markets, and reduce costs for farms to transition to organic.

Taken as a whole, Hoefner says, the programs amount to about $175 million per year—less than 1 percent of the non-food stamps portion of the farm bill. “These programs make up an extremely modest portion of the farm bill’s budget, but they’ve had a large impact on communities nationwide,” Hoefner said. Hoefner pointed to a wide-ranging recent USDA study documenting positive impact of the programs.

And now they’re all on the block, Hoefner says. The issue is that these programs won mandatory funding in the 2008 farm bill, but will lose that status on Sept. 30. If Congress does manage to pass a new farm bill by the deadline, there will be strong push to kill the programs in the name of fiscal rectitude. (GOP stalwarts like ag committee member Sen. Pat Roberts (R-Kansas) are already taking aim at Know Your Farmer.) And if Congress fails to put together a new farm bill and instead temporarily extends the old one, the programs will likely languish unfunded, stripped of their “mandatory” status. And if that happens, it will be extremely difficult to revive fuding for them when Congress finally does get around to passing a new farm bill.

“The second half of April could determine whether or not we’ll have government support for sustainable farm and food programs for the next five years,” Hoefner said.

• Big Ag continues to get support for monster corn and soy crops. Large commodity growers will take a nominal hit in the next farm bill. For years, farmers in a few chosen crops—corn, soy, cotton, etc.—have received $5 billion per year in so-called “direct payments” based on the acreage under production. In order to receive direct payments, farmers had to sign so called “conservation-compliance” agreements, which obligated them to create conservation plans for highly erodible land and agree not to drain wetlands for planting. The conservation-compliance agreements were far from perfect, Hoefner says, but they did help slow soil erosion in the Corn Belt for years.

In the next farm bill, direct payments will almost certainly be scrapped, Hoefner says, and replaced by a revenue-insurance scheme that is projected to cost $3.5 billion per year, saving taxpayers $1.5 billion per year. Sounds like a step forward, right? Wrong. First of all, in current negotiations, there is no conservation-compliance requirement for revenue insurance—meaning that farmers will have incentive to drain wetlands to grow crops, as well as expand crops onto erosion-prone land. Moreover, the new scheme will likely insure prices at high levels—meaning that relatively small price dips could cost taxpayers serious money, potentially wiping out that promised $1.5 billion in savings.

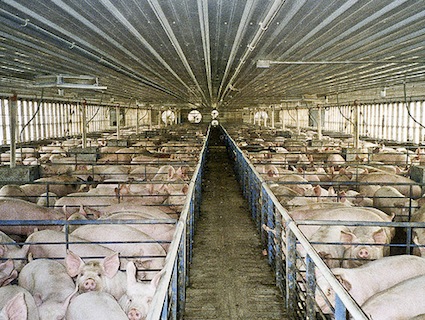

The switch to revenue insurance, Hoefner says, will “further reduce the risk of putting the pedal to the metal on commodity production, [with] no incentive whatsoever to diversify crops or leave any ground unplanted.” All of that, of course, is manna to the companies that supply inputs to industrial-scale farmers: seed and pesticide companies like Monsanto and Syngenta; and to the companies that buy corn and soy and transform them into a range of low-quality, profitable foods.

The picture Hoefner paints is grim. At a time when the public is increasingly demanding a more sustainable and healthy food production system, Congress is in the process of enshrining agribusiness as usual—pinching the pennies that go to sustainable food programs while propping up destructive agriculture tailored to the profit needs of agrichemical companies like Monsanto.