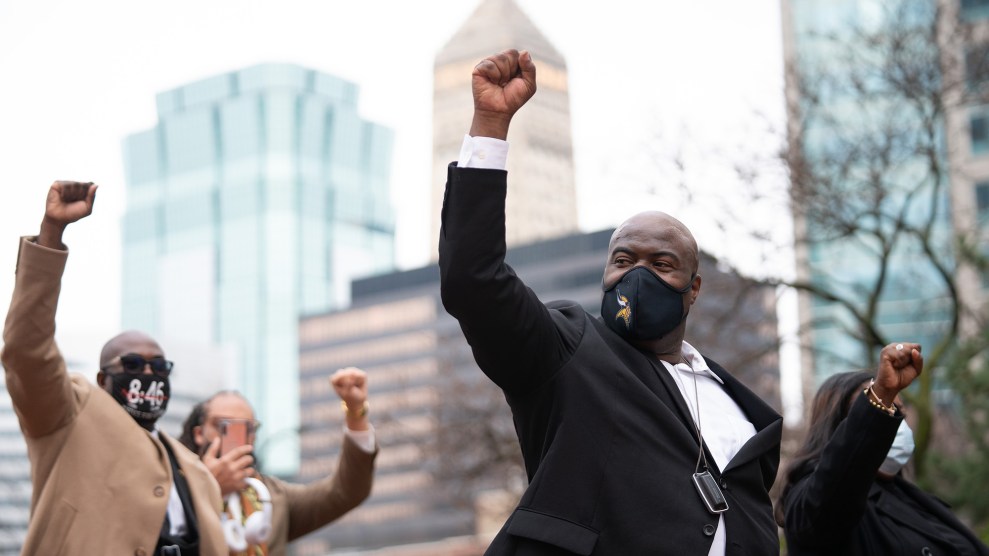

Jim Vondruska/AP

In the wake of the widespread George Floyd protests last year, Republican lawmakers across the country flooded the zone with so-called anti-riot bills. Last month, Florida’s Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis signed into law the draconian “Combating Public Disorder” measure that expands the definition of riot to mean a “violent public disturbance involving 3 or more people,” increases the penalty for participating in a riot, and gives police the discretion to decide what a riot is—and isn’t.

“The criminal aspects of this bill are already illegal,” Florida Agriculture Commissioner Nikki Fried said. “[It] protects no one, makes no one safer, and does nothing to make people’s lives better. It’s simply to appease the Governor’s delusion of widespread lawlessness.”

Despite being criticized for extremism, dozens of Republican-dominated states like Ohio and Arizona have similar measures succeeding in state legislatures and on their ways to become laws. “I think you’re going to see other states sort of picking up the ideas as well, so yeah, this is a real victory for him,” Florida State University Professor Carol Weissert told an NBC affiliate.

According to the International Center for Not-For-Profit Law, there are 69 anti-protest bills pending across the nation. These proposals vary, but many of them expand the definition of rioting in such a way that it can potentially entrap peaceful protesters, while increasing penalties for unlawful assemblies, and offering civil protection for people who injure protesters like, say, individuals who ram their cars into demonstrators on the street.

This wave of extreme anti-protest bills signals a new era in the post-Trump Republican Party. The GOP has not only criminalized protests, they have also made it harder to vote and restricted abortion rights, all the while riling up and pandering to their largely white and fearful base. The party offers little in terms of substantive policy, instead choosing to focus on suppressing civil rights and engaging in dumb but still-dangerous culture wars. Not long ago, these types of bills may have been considered too extreme to become law, but now the flood gates have opened, and the anti-protest bills are rocketing through state legislatures, undermining both constitutional rights and efforts for police reform.

After Derek Chauvin murdered George Floyd in Minneapolis last year, protests in every state erupted in response to the viral video of his death. The unrest sparked a national reckoning on race, policing, and justice, with a commitment from liberal politicians to reform police. But while advocates and activists pushed for change, conservative politicians have attempted to double down on the very conditions that triggered the demonstrations in the first place. By criminalizing an increasing number of what should be constitutionally protected activities, these bills only sanction more police interactions with the public.

One of the major obstacles to police reform has been entrenched approaches by law enforcement officials. Many departments or agencies are reluctant to change and are backed by powerful unions, who see reform efforts as a direct attack on the people they represent. But these bills offer seemingly unlimited opportunities to come into contact with police officers because of our obsession with criminalizing actions, like walking in public, which in most other circumstances would be just a part of daily life. If one of the goals of police reform is to end police brutality, that won’t happen as long as Republicans continue to introduce bills that add to the long list of criminalized activities—including exercising the right to protest.

In Florida the broad definition of what counts as a riot is what has advocates worried. For instance, the new Florida law makes it a crime to use what they refer to as “mob intimidation,” which they define as when three or more people “gather to threaten to force another person from taking a viewpoint against their will.” Hypothetically speaking, if three people are wearing Black Lives Matter t-shirts and are trying to engage a passerby, what happens if that person decides they’re all secretly Antifa? Is that mob intimidation? Who decides how to interpret that?

“[The legislation] is racist, unconstitutional, and anti-democratic, plain and simple,” Micah Kubic, the executive director of the ACLU of Florida, said in a statement after it became law. “The bill was purposely designed to embolden the disparate police treatment we have seen over and over again directed towards Black and brown people who are exercising their constitutional right to protest.”

The dynamic implicit in the dozens and dozens of laws currently in state legislatures is that of a political party deeply invested in paring down civil rights. In Iowa, both chambers of the state legislature introduced similar anti-protest bills that would increase the penalties for a “riot” from an aggravated misdemeanor, to a felony punishable by up to five years in prison. The bills also enhances the punishment for “unlawful assembly” by those who block streets or sidewalks during protests, and provides immunity for drivers who happen to injure protesters who are unlawfully assembled.

In South Carolina, a bill introduced in December 2020 criminalizes blocking a street or sidewalk during a protest, a crime punishable by three years behind bars. The legislation also changes the state’s rioting laws to require anyone convicted of rioting—including “by being personally present [at], or by instigating, promoting, or aiding” a riot—to pay restitution “for any property damage or loss incurred as a result.” Lastly, the bill provides civil immunity for a person who uses deadly force or points a firearm when “confronted by a mob,” a callback to the Missouri couple that pointed guns at protesters last year and were subsequently charged with unlawful use of a weapon and tampering with evidence.

And in Wisconsin, lawmakers introduced a bill that expands the definition of a riot. Under the proposed legislation, an “unlawful assembly” during which at least one person commits an act of violence or threatens to constitutes a riot. In practice, according to the ICNL, a large street protest can become a riot if just a single person commits violence or threatens it.

After hundreds of Trump supporters stormed the US Capitol building on January 6 during the routine count of electoral college votes, assaulting police officers and chanting “Hang Mike Pence,” the Republican party went on the defensive. They conflated the insurrection, which left six dead, including a police officer, and scores more injured, with the George Floyd protests during the summer of 2020. “The left in America has incited far more political violence than the right,” Rep. Matt Gaetz (R-Fla.) falsely implied in the aftermath of the insurrection. “For months, our cities burned, police stations burned, our businesses shattered.”

But as much as the GOP wants to draw parallels between the two events in order to deflect from their own culpability in the attack, there is no better indication of just how deeply corrupt they are than their behavior during the aftermath. The GOP has largely resisted an investigation into the January 6 attack, voted to acquit former president Donald Trump, and created dozens of bills intended to suppress any future racial justice protesters.

When Gov. DeSantis signed the new anti-protest bill into law shortly after Derek Chauvin was convicted of murder, the Trump protegé expressed disappointment at the police officer’s guilty verdict. In so doing, he signaled that the bill just might be less about so-called rioting and more about interfering with police reform attempts. “I can tell you that case was bungled by the attorney general there in Minnesota,” he said. The message he appeared to be sending was clear: Floridians could be assured that no such unsavory verdicts would occur in the Sunshine State. Why? Because this new law was, according to the governor, the “strongest anti-rioting, pro-law enforcement piece of legislation in the country.” As far as he was concerned, that’s the only reform that was necessary.