Over the past four decades, private equity has become a powerful, and malignant, force in our daily lives. In our May+June 2022 issue, Mother Jones investigates the vulture capitalists chewing up and spitting out American businesses, the politicians enabling them, and the everyday people fighting back. Find the full package here.

“How do we extract the most value from the patient we’re killing?”

We had maybe 25 to 30 people on the editorial staff when I started at the Mercury in ’97. Ten reporters. Lots of copy editors. Weekend editors. Features editors. It was a bustling place. I was very surprised at how much news there was in Pottstown, Pennsylvania, a town of 21,000 people. But when you cover everything, there’s a lot.

There’s no point on the timeline where you can say, “This was when it started shrinking.” There were always financial constraints. Whenever anyone left, there was always the question of, “Will they be replaced?” The benefit of being in a union was the longer you could hang on, the harder it was for them to get rid of you.

We got purchased in 2001 by a notoriously cheap chain called Journal Register Company. We had a union contract that spelled out the number of reporters we would keep in the newsroom. We had, I think, two more than the contract required. They immediately laid off those two people.

Under JRC, we went through, I want to say, two bankruptcies. During that time, we would give up concessions to keep the place going. Finally, JRC went under. Alden [Global Capital, a hedge fund that has partnered with PE firms in some of its biggest newspaper takeovers] bought the company. They appointed a new board of directors. To their credit, they got a guy named John Paton. He actually wanted to try to save newspapers. For about two years, it was an exciting time.

Finally, Alden got tired of the bleeding. Almost every quarter, or every other quarter, you would get an email that said, “We’re looking for volunteers to quit.” It wasn’t about, “How good is the paper?” It wasn’t about, “How do we raise revenues?” It was always just about, “How do we get to this profit percentage?” The answer was always cut, because you don’t have to spend money to do that. They had this brutal phrase they called rightsizing. But we never seemed to get to the right size.

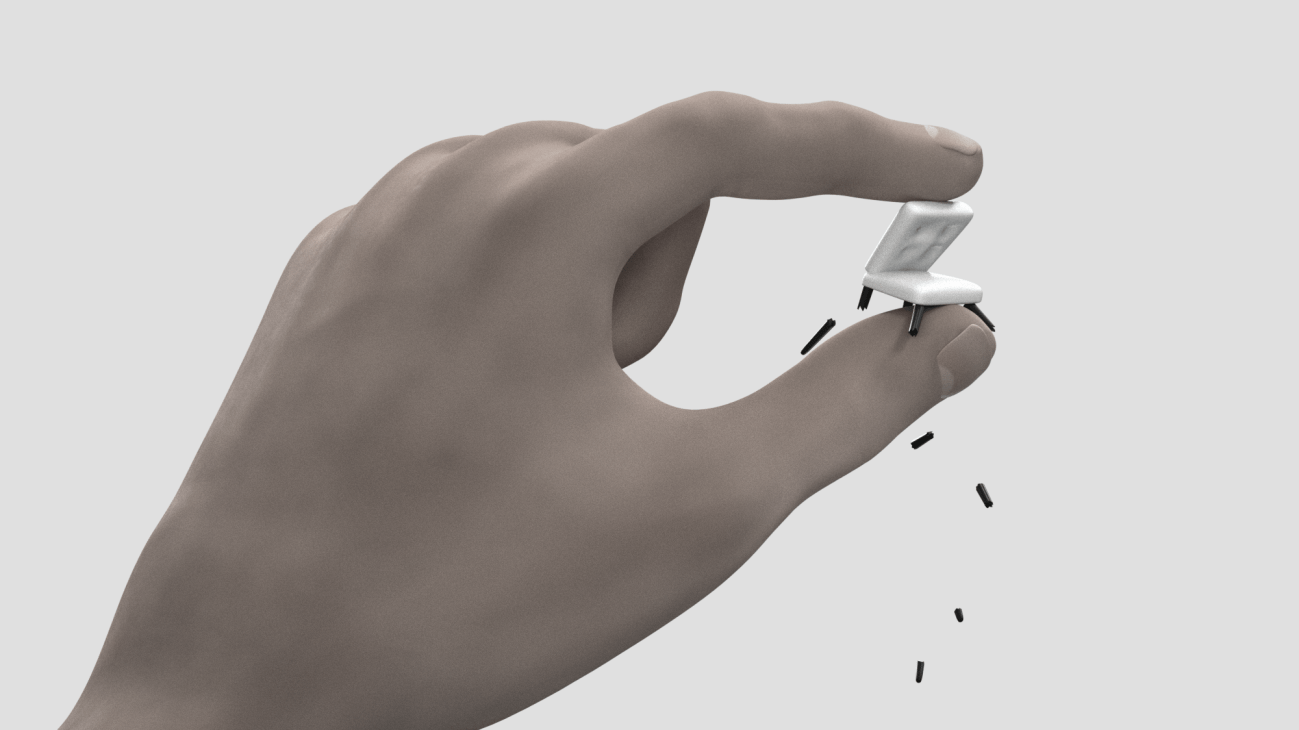

When I realized that the actual plan was to kill us and just to do it slowly, that’s when I really began to get my back up. This wasn’t just us suffering layoffs and cuts because of a dying business model. It was a managed decline. How do we extract the most value from the patient we’re killing? We were working harder and harder for people who didn’t care who you were, didn’t care what you were doing, didn’t care what you were trying to do for the community. They were only interested in the number next to your name: your salary. Finding out how much money Alden was making was kind of the break point for me. (Alden did not respond to requests for comment.)

I would say I’m the last guy at the paper devoted to Mercury coverage. Although stories about budgets, big expenses, local officials behaving badly are not always the most read stories, they’re what I call constitutional functions for the local press. We don’t have a First Amendment so I can cover a car crash.

Other people who work for the paper don’t work in Pottstown anymore. They work either at home or at the printing plant, which is where my official office is. I can’t ask the company to reimburse me for expenses for a home office because their answer is you got an office down here whenever you want. You could work at home, or you could drive 40 minutes south, clock in, drive 40 minutes back to cover things in Pottstown, then drive 40 minutes south, write it up on a computer in the office, then drive 40 minutes home.

I just laugh at it. I could get supplies there, but it’s such a pain in the ass. I just go to Staples. The first time I did that, I put in an expense. I got called by the deputy publisher, who said, “Don’t ever do that again. If you want supplies, you can come down here.” I’m like, do you have a great deal on notebooks? Because I used a coupon.

I ended up at Alden president Heath Freeman’s house after Julie Reynolds wrote a story about Alden that ran in the Nation. She used land records to report that Freeman had just purchased this house out in Montauk. She used the records to determine that not only had he bought the house and a pond next door, but he was expanding the size of the house by a third. Most frustratingly, she calculated how many reporters could have kept their jobs for another two years for what he spent on that mansion.

My wife, my son, and I were driving out to the end of Long Island, where my father and my stepmother live. I thought to myself, maybe I’ll go look. Maybe I’ll go out there and get a picture. Then I thought, maybe I’ll take a picture and put it on Twitter. Maybe I’ll be in the picture. Maybe I’ll hold a sign. My wife, who has way better penmanship, wrote me up a sign with the Newspaper Guild mantra of the day, “Invest in us or sell us.” I was wearing a shirt that said, “News Matters.” We stood in the driveway. My stepmother took my picture.

Then, a woman who I assumed to be Mr. Freeman’s wife drove out to the end of the driveway. She rolled the window down and asked if she could help me. I asked if Mr. Freeman was home. She looked at my shirt and my sign and said, “No, he isn’t.” Then I heard Dave Matthews blasting from the back porch. I thought, yeah, he’s home. So, what do you do? I’m not going to go yell at my boss and tell him you’re ruining my life and destroying journalism. Because he’d made it pretty obvious he didn’t care about that.

I decided I’ll interview him. I’m walking up to his door from the driveway thinking you’d be lucky to get one question. The question I came up with was “What value does local news have?” Not “How much can you sell it for? What’s its value?” I never got to ask that question. A housekeeper opened the door. He was at the top of the stairs. She said, “This man’s here to see you.” Like wife, like husband: He took a look at me and my shirt, and he just shook his head and walked away.

The real evidence of their disregard for the whole operation is they left everything when they sold the building. They left the desks. They left the filing cabinets. They left filing cabinets with people’s personal financial information, people’s Social Security numbers, people’s pay stubs. They left probably the most valuable asset we had, which was the clip files. Forty or 50 years of clips of everything that’s happened in the town.

They sold the building to a woman who runs an engineering firm across the street. She is in the midst of converting it into a boutique hotel and whiskey bar. I think the clientele she’s eyeing are the parents of Hill School students. They haven’t taken the sign down yet. My guess is they’ll leave it there for the cachet. I wouldn’t be surprised if the bar was called the Press Room or something like that. I think people whose kids go to the Hill School would love the charm and nostalgia of that. —Evan Brandt as told to Noah Lanard

“Bain is going to suck every penny out of it.”

I’ve been with Bob’s Discount Furniture for a little over 10 years. Originally, Bob’s felt like a smaller company. We had managers that would support us. There were cafes in the store. They’d serve fresh cookies. There was a pond with actual fish swimming around. It was a nice place to work.

After Bain bought us, things slowly started to change. There was a lot more of a workload. Management changed, too. We lost our regional manager, who was in furniture and knew sales. We started getting new regionals who were ignorant to the industry and just started micromanaging.

Another big thing that changed was HR. We used to have an HR person who would come to the store. Now, HR is a number that’s posted on our walls—sometimes. I have reached out to HR and never had my call returned.

It’s like you go from working for this small company that cares about you to working for this corporation where you’re just a number and totally replaceable—just used and tortured in a weird way. I’ve never met anybody who works for Bain.

There was a lot more of a workload put on us. Instead of just focusing on sales, we were also doing customer service work. So, if I sell something to you, and it’s not available or anything happens, I’m the one who reaches out to you. I’m taken off the sales floor to do that kind of thing.

Before Bain, I would say an average salesperson made maybe $60,000 a year after commission. Then, with all the changes, there was a year that I dropped by $20,000.

It was probably about three years after Bain took over before we all started realizing that this is just getting worse and worse. There were other stores close to us that had already unionized. We decided it was something we wanted to move forward with. We had strong opposition from Bob’s.

A few weeks out from the vote, they had everybody come in. We got to meet our HR representatives for the first time. We had the vice president of sales. We had regional managers come in and tell us why we shouldn’t unionize.

We started seeing delays in merchandise when the tariffs started with China. Then with Covid it got to a point where our company can’t even supply furniture. We spend hours with a customer. We set up delivery. Then four months down the road you cancel because you’re frustrated. I get paid $0 for it. We don’t get paid anything until we deliver it to a customer’s home.

At the beginning of this year, I was just breaking commission, so just making $400 a week. Not because I’m not performing but because I can’t deliver anything. There’s been a huge turnover. I think the fact that there’s no furniture to even deliver is the final straw for most people.

They’ve lost a lot of their customers, too. There’s a review that’s sent to you after your purchase. The review says, would you recommend Bob’s to a family member or friend? Management says that’s based on you, so you have to get the review. If we get a bunch of positive reviews, it’ll take away all the negative reviews that the company has because of not being able to deliver. (A Bob’s spokesperson told Mother Jones that the company was just one of many affected by global supply chain disruptions due to the pandemic, and that the problems were not related to its private equity ownership.)

We’ll walk into a room and there’ll be a big poster that says like, “We only had five reviews yesterday. Obviously, you people don’t care enough. You don’t try.” It’s all in angry red markers. They’ll say, “I don’t know when you guys stopped caring.” They’re insane. They’re screaming in your face. They have no problem saying these things on the floor in front of customers. It’s coming from above and trickling down.

We are hoping that the union negotiations go through soon and it goes back to a simpler thing. But I don’t know.

I think they’re a sinking ship. If you’ve been there long enough, you know what it was like before. Now there aren’t any fresh-baked cookies. There aren’t any ponds left in the stores. Bain is going to suck every penny out of it and then discard it once they’ve completely ruined it. All of us salespeople, that’s how we feel. Once the last penny is out of the jar, they’ll sell it. —Anonymous as told to Noah Lanard

“You’ve only got 30 minutes to take care of all these animals.”

One day I went into PetSmart with my dog, Bandit, and he did this really funny trick where you’d say, “Who’s the president?” and he would say, “Oh, bah, bah.” Everybody in the store was laughing and giving him treats. It was such a family feel. The assistant manager came up to me and said, “We’re looking for a dog trainer.”

That feeling played out the first six months. I loved the atmosphere. I loved the customers. I loved the people I worked with. I thought, “This is where I’m going to retire.” I worked retail jobs for a long time, and it just felt like something really special.

About two months in, I came to work and corporate was there, and they said, “You have a new manager.” I really liked the new manager, but the whole atmosphere of the store started to change slowly after BC Partners bought PetSmart. Within a year, it was really different.

Job positions started to disappear. They used to have a dedicated pet care person, and suddenly that person was eliminated. Everybody was having to do a whole lot more. It didn’t seem smart, especially when you’re working with live animals. It just leads to a lot of neglect. Not out of any kind of incompetence—there’s just not time to get the jobs done. If you don’t have enough staff in the groom salon to hold a dog that’s bitey or clawing or wiggling around, you risk nicking the dog, you risk being bitten, you risk the dog getting off its slip lead and attacking another dog.

The animals that the store sells, you don’t have time to properly take care of them. They also cut closing from two hours to 30 minutes, meaning you don’t close the animal sales until 30 minutes before the store closes, and then you’ve only got 30 minutes to take care of all these animals that are for sale in the store. That made people feel obligated to work so much harder for so much less money. They were just cutting corners. (In a statement, PetSmart said, “While we are unable to provide specific details related to an associate’s termination, we can confirm that Mr. Allen’s termination was unrelated to his Facebook activity.”)

Then, when the pandemic hit, we walked in one day and they said, “You’re gonna be furloughed. You may or may not be hired back. But during the time that you’re furloughed, you can’t do any animal-related work or you’re subject to not being rehired.”

During the furlough, I started a Facebook group that had about 700 members. It was all employees who were furloughed, laid off, or terminated due to Covid, and just helping them figure out what to do because we got no cooperation and no information from HR.

They called us back from furlough in, I think, the last week of June. The first day I was there, they wanted to know about this Facebook group I’d started. They said, “That amounts to working off the clock, and you weren’t supposed to be working during furlough.”

I ended up getting terminated, and I felt like it was because of the work I was doing with the Facebook group. I don’t know why that was so threatening, but that was a big deal. They told me I had to disband the Facebook group, and I did say, “No, I’m not gonna do that.”

Still, it felt terrible. It was embarrassing because I was very close with the clientele. This is a small town. All people know is they go in there and I don’t work there anymore.

I had a sense after the discussion about the Facebook group that I probably had a target on my back, so I stopped at a Petco. I said I’ve been dog training a long time, and the lady that managed that store said, “Well, we’re hiring a trainer right now.” The night I was fired, I called that Petco and talked to the manager, and I was upfront with her about what had happened at PetSmart. She said, “I checked out your reviews online. You have a lot of really happy, really loyal customers. PetSmart’s loss is gonna be our gain.” I was teaching class at Petco the day after I was fired. —Robert “Happy” Allen as told to Abigail Weinberg

This story has been updated with comment from PetSmart.