Over the past four decades, private equity has become a powerful, and malignant, force in our daily lives. In our May/June 2022 issue, Mother Jones investigates the vulture capitalists chewing up and spitting out American businesses, the politicians enabling them, and the everyday people fighting back. Find the full package here.

If you were to sit down with a focus group and a whiteboard, you would have a hard time coming up with a policy with less populist appeal than the nearly three-decades-old loophole that cuts private equity billionaires’ tax rate almost in half.

The carried-interest loophole, Barack Obama said, upset “the balance between work and wealth.” Donald Trump claimed the fund managers who availed themselves of this tax break were “getting away with murder.” Joe Biden, like both of his predecessors, ran for president on a pledge to end it.

For more articles read aloud: download the Audm iPhone app.

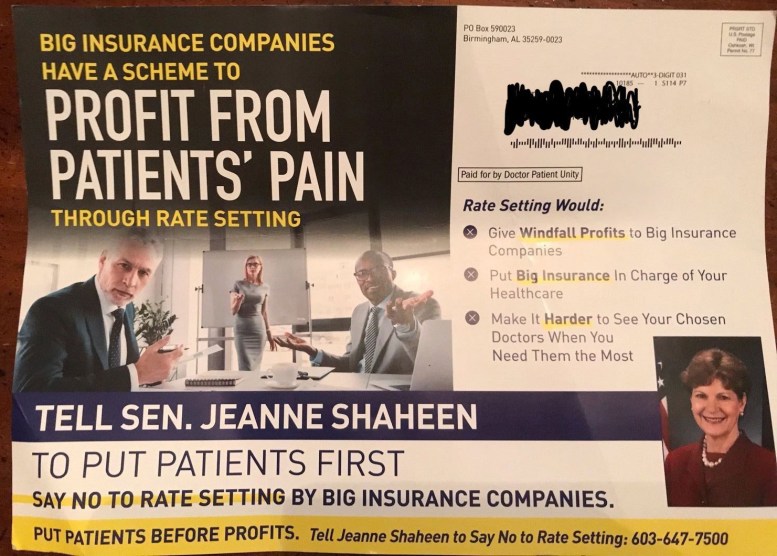

“People get this really easily—we’re giving a whole lot of rich people more money for no reason other than them being rich,” says Mandla Deskins, advocacy manager at Take on Wall Street, an organization pressuring members of Congress to jettison this tax break.

On paper, it’s an idea that almost nobody says they want. Polls show the public is overwhelmingly against it. Mitt Romney lost his bid for the presidency in part because of it. Tax experts think it’s unfair. Carried interest has no real constituency outside certain corners of Nantucket. But for a decade and a half, private equity’s favorite tax break, which delivers hundreds of millions of dollars annually to the guys in blue button-downs and matching fleeces who bought your company and laid you off, has been the most unkillable bad idea in a town with no shortage of them, a testament to the unstoppable combination of money and inertia.

Well, money mostly.

“It’s not necessarily dead,” Deskins says of the most recent effort to close the loophole, “but it is definitely on pause.”

The concept of carried interest is quite old, and in the right circumstances, makes a good deal of sense. By the 13th century, Venetian investors were offering seafaring merchants a quarter of the overall profits in exchange for selling their goods in foreign markets. That percentage was the carry—it was a return on what we’d call the merchants’ sweat equity. Private equity firms, which pool money from investors such as pension funds and use it to buy and restructure (euphemism alert!) existing companies, borrowed the concept, but not the risk. They typically take a 2 percent annual cut of the assets they manage as a fee, and then a 20 percent share of the profits when those assets are sold. There’s no sweat equity—the only time private equity titans brave the high seas is on a yacht—but there also isn’t much regular equity, either. The firms’ final take is vastly disproportionate to whatever small sum they might have contributed.

On paper, this payment system—dubbed “2 and 20”—shouldn’t represent much of a taxation quandary. By the time boutique private investment shops began popping up in the 1980s, the IRS had long distinguished between investment income (such as capital gains) and regular income (such as a salary). If a firm wanted to be paid with a percentage of future profits like the Venetians of yore, that percentage would still be taxed as regular income. It was understood to be a form of compensation: A firm was not cashing in on its own investment; it was taking a very large chunk of its clients’ investments as a reward for managing them. Workers in other sectors who receive performance bonuses or commissions treat that extra money as regular income. But investment firms challenged this classification, and in 1993 the IRS quietly tweaked its rules. Private equity firms could consider their precious “20” to be capital gains.

At first, this distinction didn’t mean much. In the 1990s, the tax rates for investment and ordinary income were roughly even. But President George W. Bush’s 2003 tax cut slashed the capital gains rate. Suddenly financial managers had a huge incentive to take advantage of the discrepancy—and private equity, by paying far less to Uncle Sam, picked up an enormous competitive advantage over other forms of investment. In 1980, PE was a $5 billion niche industry; by the 2000s, firms managed more than $1 trillion in assets.

Private equity’s vertical growth didn’t go unnoticed—nor did its unusual tax bill. In early 2007, then-Rep. Sander Levin, a Michigan Democrat (and brother of the late Sen. Carl Levin), was having dinner with an old classmate in Boston when the friend, a tax attorney, told him about 2 and 20.

“He had clients who used it, and he thought it was a loophole that was inadvisable,” Levin told me.

Levin started looking into it and agreed. That summer, on the day the private equity giant Blackstone Group went public with a $4.1 billion IPO, he introduced a bill to make carried interest subject to regular income tax rates. Investment managers paying a lower tax rate “than teachers and firefighters” was a rhetorical device anyone could understand. Obama, locked in a tough Democratic presidential primary, took aim at the loophole. Hillary Clinton, otherwise a Wall Street ally, joined the pile-on. Even the Senate Finance Committee, a magnet for industry cash, held hearings on the subject and considered a bipartisan proposal to raise the effective tax rate on private equity and hedge funds.

Closing a corporate tax break was a nonstarter in the Bush era, but when Democrats assumed full control of Washington in 2009, amid the Great Recession and a popular backlash against Big Finance, it appeared that private equity would have to start paying its fair share.

How much revenue closing the loophole would generate was (and is) a matter of debate. Victor Fleischer, a law professor at the University of California, Irvine, and former counsel for the Senate Finance Committee, has calculated that it could amount to as much as $180 billion over 10 years. Projections from congressional analysts put the figure much lower—from $14 billion to $18 billion over the same period. It all depends on just how successful private equity managers are at finding a workaround. (Historically, they are very good at this.) Whatever the actual number is, though, there’s an underlying imbalance to the fight; the price tag of ending carried interest is small enough that lawmakers can afford to triage it and large enough that the industry can’t.

“Once I introduced it, I found I was kind of tackling a whirlwind,” Levin, who retired from Congress in 2019, says of his bill.

In 2006, before the carried-interest fight began, private equity and investment firms spent about $3.6 million on DC lobbyists; over the next four years they spent a combined $75 million. And they pumped tens of millions into Democratic and Republican campaigns—still a pittance compared to what they stood to lose if the rules were changed. In the runup to the 2010 midterms, Blackstone CEO Stephen Schwarzman told a nonprofit board that Obama was at “war” with his industry. It’s “like when Hitler invaded Poland in 1939,” he said. But Schwarzman, who pocketed $78.4 million in carried interest in 2020, needn’t have been so worried about a blitzkrieg. Obama had asked Congress to end special treatment for “investment fund managers” in his first State of the Union address, and publicly the administration expressed confidence that the tax break was on the outs. But the White House never leaned on senators to include carried interest in a tax reform push, according to the New Yorker. And with the Republican minority filibustering every bill that passed to the floor, the industry had math—and time—on its side.

The finance committee chair, Montana Democrat Max Baucus, was a longtime industry ally, and Democrats argued over proposals that would slow the implementation of the rule change and allow managers to still keep a large percentage of the carry as capital gains. When the Senate finally considered a bill that would have fixed the loophole, Evan Bayh was one of 11 Democrats (plus the independent Joe Lieberman) to vote against a procedural motion to advance it. An aide told the press that the Indianan was opposed to a provision in the legislation concerning low-income housing; seven months later, Bayh took a job at the private equity giant Apollo Global Management. Another version of the repeal came up for a vote in June 2010, and this time Democrats had 57 votes for passage—but Nebraska’s Ben Nelson helped Republicans block it.

The House passed a version of Levin’s legislation four times, but after the 2010 tea party wave, carried interest mostly went from a legislative fight to a campaign issue. Obama, who couldn’t fix the problem with a Senate supermajority, tarred his 2012 challenger Mitt Romney for taking advantage of it as CEO of Bain Capital. When Clinton launched her second presidential campaign, carried interest was one of the first things she brought up.

Hammering home the discrepancy between the average person’s tax bill and a vulture capitalist’s is the kind of economic story Democrats want to tell. But the fact that they’re still hammering it home hints at something else. There’s an obvious tension between the party’s rhetoric and its Rolodex. Large private equity firms and hedge funds have filled Democrats’ coffers for years and served as a comfy landing pad for ex-politicos such as Bayh and Lieberman. Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner—who once urged Congress to tax private equity “the same way we tax the income of teachers and firefighters”—left the Obama administration for a job in PE. Bill Clinton’s first post–White House job was with a PE firm run by a billionaire donor. In 2014, Joe Biden spent Thanksgiving at a 13-acre Nantucket estate belonging to the co-chair of the Carlyle Group, David Rubenstein—himself a former Jimmy Carter staffer. (Bayh stayed there in 2010.) Ex-staffers for Nancy Pelosi and Chuck Schumer lobby Congress on behalf of the industry today. Asked in 2015 about the possibility of the next Democratic administration closing the loophole, the anti-tax crusader Grover Norquist likened the situation to the old adage about a dog chasing a bus it never intended to overtake. “You didn’t mean to catch the bus,” Norquist said. “You meant to whine about the bus.”

Instead, it was Donald Trump’s turn to whine. Attacking a legal form of tax avoidance was an easy message for a candidate whose whole shtick was accusing other people of the things he was already doing. “They’re paying nothing, and it’s ridiculous,” Trump, who really did pay nothing in taxes for multiple years, said of private equity managers. “These are guys that shift paper around and they get lucky.”

But when Trump rewrote the tax code in his first year in office, the loophole survived largely intact. “We probably tried 25 times,” said his then-adviser Gary Cohn, pointing the finger at Capitol Hill. But congressional Republicans had a natural ally in Trump’s treasury secretary, Steve Mnuchin, who prior to joining the administration operated a hedge fund named for his Hamptons estate. Mnuchin brokered a compromise—the law would slightly lengthen the period investment managers would be required to hold onto an asset before selling it, but the tax break would survive. An industry lobbyist told the New York Times he’d feared Trump would blow the deal up with an “errant tweet.” But for once, none came. It was “not that much money,” Trump explained afterward; he’d traded it for a “much better deal.” Mnuchin, for his part, rejoined the private sector last year—and promptly raised $2.5 billion for a new venture in private equity.

Closing the loophole remains popular. A 2019 survey from Lake Research showed 77 percent support for ending policies “that let private equity executives avoid paying their fair share of taxes.” And tax experts are even more united in their opposition. Last summer, Jonathan Choi, a law professor at the University of Minnesota, surveyed 167 of his fellow tax-law professor colleagues and found that just 10 supported the loophole as it currently stands. Of the 17 tax-reform ideas surveyed—including a wealth tax and an expansion of the child tax credit—eliminating the carried-interest tax break was by a considerable margin the one that came closest to consensus.

“The reality is that these industries are extraordinarily lucrative,” Choi says. “We can look at comparable investors and see that they’re not stopping and closing up shop just because they have to pay ordinary rates of tax. Most hedge fund managers now pay ordinary rates of tax, but that hasn’t stopped them from operating in the United States, or from doing what they would ordinarily do.”

It’s the nature of carried interest that senators don’t spend a lot of time giving speeches in its defense. Instead, lobbyists play up the effect that changing the rules would have on, for instance, real estate developers who form partnerships to construct housing and commercial space. The American Investment Council, the private equity industry’s main lobbying group, likewise suggests that closing the loophole would hurt not Schwarzman, but the “schoolteachers and first responders” whose tax rate his is so often compared to—because public employee pension funds are heavily invested in private equity. In this line of thinking, the capital gains discount incentivizes investors to take risks; lessen that incentive and you’ll lower the investment returns. But that supposes that pension funds were getting an unbeatable deal to begin with; studies have found that retirement programs would do just as well investing in ordinary index funds (which do not, after all, take 20 percent of your profits).

What the private equity industry understands about Washington is that power is expressed in the rules not made and the votes not taken—in making yourself cumbersome enough to move that legislators eventually get tired and move on. Since the loophole was originally created through the IRS’s rulemaking process, it could theoretically be reversed the same way. But Biden, like his predecessors, punted to Congress. Once again, Democratic lawmakers pushed legislative language in 2021 that would end the tax break, this time as part of the proposed Build Back Better bill, an omnibus package that included paid family leave and huge investments to combat climate change. And once again, the industry found an ally who could muck everything up.

“Kyrsten Sinema said she would do nothing at all on carried interest, so we’re just stuck on that,” one Democratic staffer told me.

The Arizona senator, who took a paid internship during the pandemic at a winery owned by a private equity mogul and Democratic donor, drew a hard line on ending the tax break in negotiations with the White House and Senate colleagues. In the face of Sinema’s opposition, language that would close the loophole was quietly removed. Biden decamped to Nantucket for Thanksgiving as a guest, once again, at the $30 million house that private equity built. But it wasn’t long before he was back to chasing a familiar bus.

“I’ve proposed closing loopholes so the very wealthy don’t pay a lower tax rate than a teacher or a firefighter,” Biden said in his State of the Union address in March.

“What are we waiting for?” he asked.