A week before the ninth anniversary of her son’s murder, Rep. Lucy McBath (D-Ga.) discovered that Republicans had radically redrawn her district to oust her from Congress.

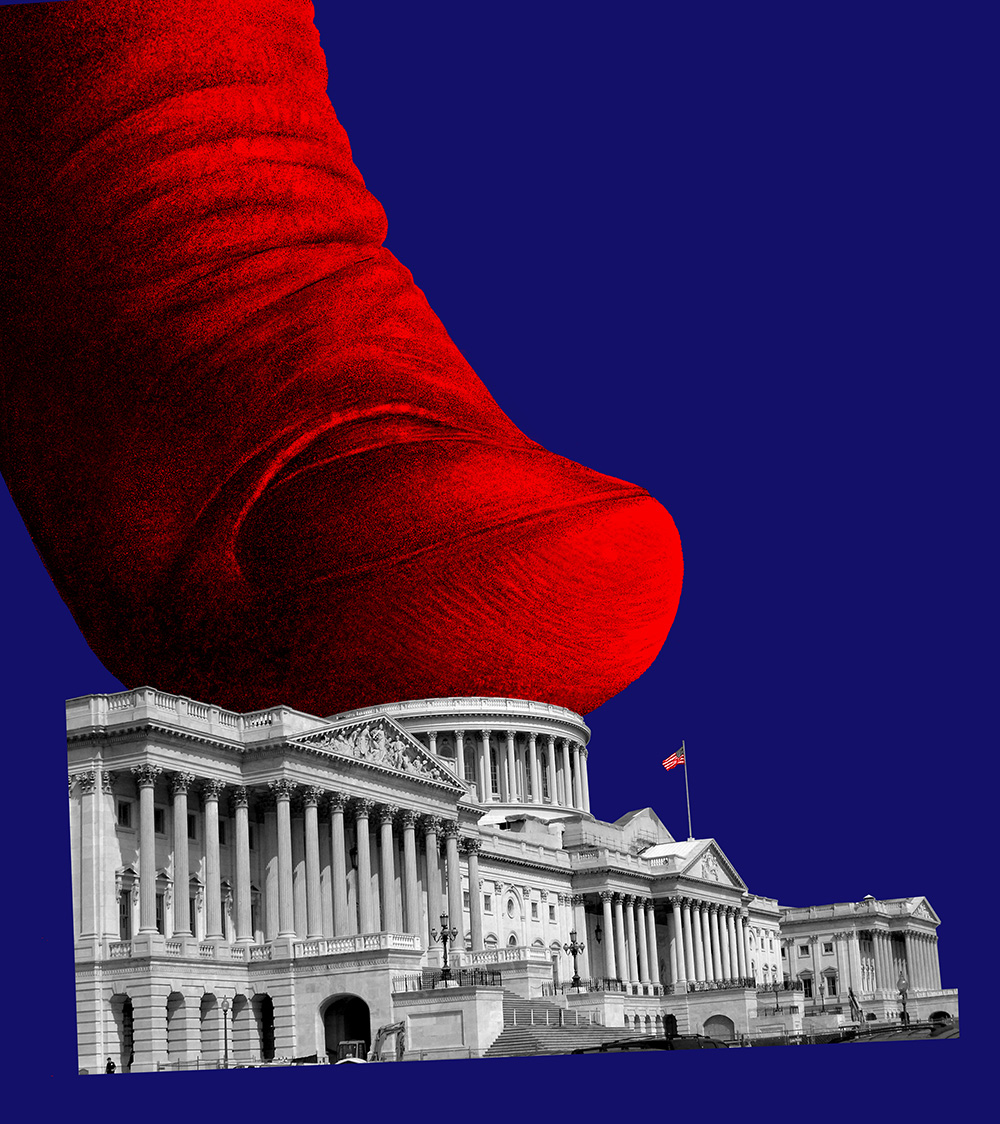

A political novice, McBath had become a leading gun control advocate after her 17-year-old son, Jordan Davis, was shot by a white man in 2012 in an altercation over the volume of rap music he was playing. She went on to stage one of the biggest electoral upsets in Georgia’s recent history when, in 2018, she became the first Black person to represent the state’s 6th District, Newt Gingrich’s home turf for 20 years. Her victory exemplified Democratic inroads in formerly red states like Georgia and the new power being exercised by communities of color in the rapidly diversifying South. But those gains are quickly being erased by the GOP through a toxic combination of gerrymandering, voter suppression, and election subversion that together pose a mortal threat to free and fair elections.

Georgia is a microcosm of the extreme tactics Republicans are using across the country to entrench power in advance of the midterms. What can appear as a series of seemingly disconnected state-level skirmishes is in fact part of an insidious national strategy that goes far beyond previous efforts to suppress and undermine Democratic influence. Fueled by the Big Lie, this effort picks up where last year’s insurrection left off by putting in place the pieces to steal future elections by systematically taking over every aspect of the voting process.

Over the course of 2021, 19 states passed 34 laws making it harder to vote—the greatest rollback of voting access since the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Those changes include more than a dozen GOP-controlled states passing new provisions to interfere with impartial election administration, while Trump and his allies aggressively recruit “Stop the Steal”–inspired candidates to take over key election positions like secretary of state offices and local election boards in major battleground states.

“What we’re seeing is a multifaceted, multilevel attack on American democracy,” says Colorado Secretary of State Jena Griswold, chair of the Democratic Association of Secretaries of State.

McBath’s district is a striking case in point: Under a new redistricting map crafted by Georgia Republicans, her diverse suburban Atlanta seat—where moderate white voters joined an influx of Black, Latino, and Asian American residents to elect her—would now stretch all the way to the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains, with Republicans adding three deeply red and predominantly white counties—Forsyth, Dawson, and Cherokee—where Donald Trump won 70 percent of the vote. (Forsyth is infamous for forcing its more than 1,000 Black residents to leave after a Black man was lynched in 1912.) Her district would go from one that favored Biden by 11 points to one that Trump would have won by 15, one of the most drastic transformations of any district in the country.

After the map passed the legislature on November 22, McBath decided to run in a neighboring district, held by Democratic Rep. Carolyn Bourdeaux, that absorbed some of the most Democratic parts of McBath’s old district. “I refuse to let [Georgia Gov.] Brian Kemp, the NRA, and the Republican Party keep me from fighting,” McBath told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution in announcing her candidacy. But even if she wins a messy primary against Bourdeaux, Democrats will have lost a House seat in 2022 in a state that is trending blue, and communities of color will have less political representation—even though they account for all of the state’s population growth over the past decade. Moreover, because of the new redistricting maps, Republicans are set to control nine of 14 congressional districts in a state where Democrats won the presidency and two Senate seats in 2020.

A similar outcome is being replicated in other key battlegrounds, like Ohio, North Carolina, and Texas, where Republican legislatures passed redistricting maps that will hand their party between 65 and 80 percent of US House seats in states where Biden narrowed the GOP’s 2016 advantage. Though Democrats are faring slightly better in the redistricting process overall compared with the last decade, these extreme maps in GOP-controlled swing states, combined with Biden’s sagging approval ratings, will likely help Republicans pick up enough seats to retake the US House in 2022 and lock in dominance of state legislatures for the next 10 years.

And make no mistake, if Republicans prevail in rigging the 2022 election, they’ll be even more emboldened in 2024, especially if Trump is on the ballot. The lies of a stolen election propagated by Trump—and exploited by Republican lawmakers who know better—are now being used to lay the groundwork to sabotage elections for real. “Their endgame?” President Joe Biden asked rhetorically during a major speech in Atlanta on January 11. “To turn the will of the voters into a mere suggestion—something states can respect or ignore.” This isn’t just about the normal ebb and flow of partisan politics; it’s a test of whether a party that is deadly serious about ending American democracy as we know it will regain control of ostensibly democratic institutions.

“The insurrection, the gerrymandering, the voter suppression, the attacks on professional election officials—all of this puts our democracy at risk to a degree we have not seen since the Civil War,” former Obama administration Attorney General Eric Holder told me recently. “That’s how serious this is.”

The targeting of McBath is not an isolated incident. It’s a stark illustration of the GOP’s nationwide playbook for undermining voting rights, with Georgia at ground zero of this battle. Georgia was an epicenter of the Trump campaign’s efforts to overturn the 2020 election, with the defeated president famously telling Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger to “find 11,780 votes” to nullify Biden’s victory. Raffensperger refused, despite threats against him and his family, but Trump’s Big Lie persuaded Georgia Republicans to pass a sweeping voter-suppression law last March that set the bar for restrictive voting legislation that proliferated across GOP-controlled states.

At the heart of Trumpism is the fear of a majority-minority future where white power no longer dominates. So it’s no coincidence that this battle is being fought hardest in the state where Black voters who vote overwhelmingly Democratic have the most to gain or lose. Along with McBath, Sen. Raphael Warnock is running for reelection in 2022 and Stacey Abrams is mounting a second bid for governor. But the voters supporting them first need to overcome more than a dozen provisions designed to reduce their access to the ballot, including a reduction in the number of drop boxes in metro Atlanta from 97 to 23, new voter-ID requirements for mail-in ballots, a far lower bar for rejecting ballots cast in the wrong precinct, less time to request and return mail ballots, a prohibition on election officials sending out mail-in ballot applications to all voters, and even a ban on giving voters food or water while they’re waiting in line.

These policies are already having an impact—during local elections in November, the number of rejected absentee-ballot applications rose from less than 1 percent in 2020 to 4 percent, according to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, a troubling indicator of how easy it would be to tilt the outcome in a state decided by just over 11,000 votes in 2020.

LaTosha Brown, co-founder of the Atlanta-based voting rights group Black Voters Matter Fund, calls the Georgia law a “death by a thousand cuts” that “has the potential to change the results of the election.” But “the scariest part of the process,” she says, is “what they’re doing with the election boards.”

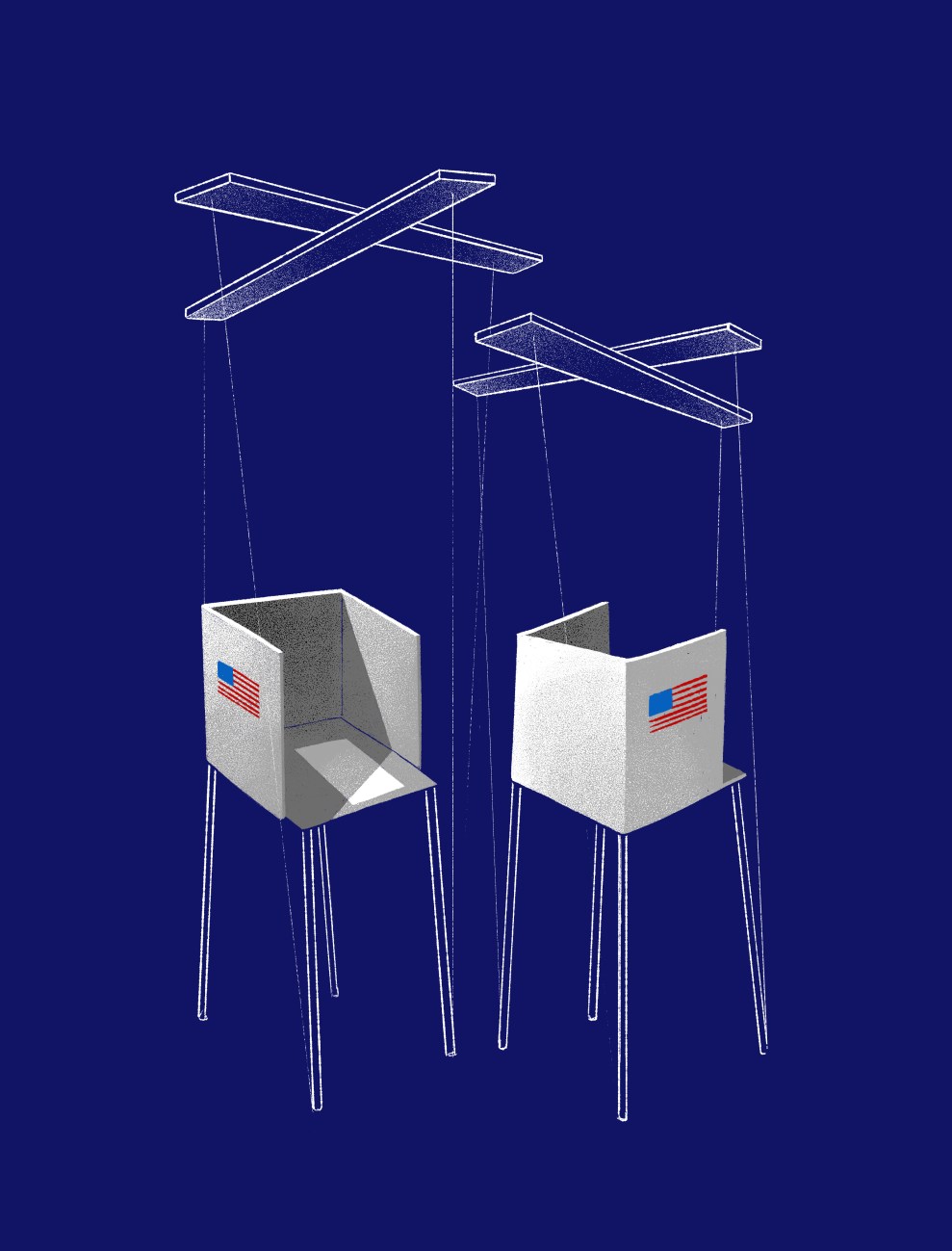

That’s right: The newest—and potentially most dangerous—anti-democratic threat are new laws designed to give Trump-backed election deniers unprecedented control over how elections are run and how votes are counted.

After Raffensperger defended the integrity of the 2020 election, Republicans removed him—and all his successors—as chair and voting member of the state election board, which oversees voting rules and election certification, and gave the GOP-controlled legislature the power to appoint the board’s chair, allowing them to control a majority of the members.

The reconstituted state board, in turn, has extraordinary power to take over up to four county election boards that it views as “underperforming” or where local officials (read: fellow Republicans) have lodged complaints. In other words, partisan election officials appointed by and beholden to the heavily gerrymandered Republican legislature could control election operations in Democratic strongholds like Atlanta’s Fulton County, where the Trump campaign spread lies about “suitcases” of ballots being counted on election night after GOP poll monitors left. The state board has already appointed a panel, led by Republicans, which immediately began a performance review of Fulton County requested by Republicans in the legislature—the first step toward a possible takeover.

Meanwhile, in at least eight Georgia counties, Republicans have already changed the composition of local election boards—which not only certify elections but determine things like the number of polling places and ballot drop boxes, as well as voting hours—by ousting Democratic members and replacing them with Republicans. Not just any Republicans, of course, but those who claim the election was stolen. (In Lincoln County, the recently reconfigured election board recently proposed closing six of the county’s seven polling sites.)

This radicalization of previously evenhanded bodies will affect not just who oversees elections, but whose votes are counted. During the January 2021 Senate runoffs, the right-wing group True the Vote challenged the eligibility of hundreds of thousands of voters who it claimed had moved. Only a few dozen votes were ultimately thrown out, but now Georgia’s new law explicitly allows an unlimited number of voters to be challenged and requires local election boards to hear these challenges within 10 days or face sanctions from the state election board. Based on these challenges, local boards could then decline to certify election results or disqualify enough voters to swing a close election—exactly the gambit Trump tried to pull off in 2020.

“More than just reducing turnout, they’re stacking the deck to actually manipulate the results,” Brown says. “That’s very scary to me.”

That’s not all. Precisely because they certified the 2020 election results, Raffensperger and Gov. Kemp are now facing Trump-endorsed primary challengers, raising the prospect that Georgia’s top executive and top election official heading into 2024 could be Big Lie champions predisposed to helping steal a future election for Trump or another Republican candidate.

Former GOP Sen. David Perdue (who lost a January 2021 runoff election to Democrat Jon Ossoff) announced in December he’d challenge Kemp. Perdue has insisted he would not have certified the 2020 election; instead, he would have called a special session of the legislature to enable Republicans to appoint pro-Trump presidential electors to nullify the will of Georgia voters. Just days after announcing his candidacy, Perdue filed a Trump-like lawsuit falsely claiming that thousands of “unlawfully marked” absentee ballots were counted in Fulton County in November 2020.

Raffensperger, meanwhile, is being challenged by GOP Rep. Jody Hice, who voted to reject presidential electors from Pennsylvania and Arizona after the insurrection, signed on to a lawsuit by the state of Texas asking the Supreme Court to throw out election results in Georgia, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin, and has said he was not “convinced at all, not for one second, that Joe Biden won the state of Georgia.”

Hice is not an outlier. More than 160 Republican candidates who’ve amplified the Big Lie are running for statewide positions with authority over how elections are run. “That’s akin to giving a robber a key to the bank,” says Colorado’s Griswold. Many more election deniers are running for local positions like poll worker and election judge. And Republicans are not coy about their intentions. “We are going to take over the election apparatus,” former Trump chief strategist Steve Bannon, an architect of this strategy, said on his podcast in late December, calling for the “overthrow” of county election clerks.

If hijacking election administration fails, extreme gerrymandering makes it more likely that Republican legislators in increasingly safe districts, insulated from public accountability, will decide to overturn the will of their states’ voters in presidential contests.

After new redistricting maps were passed in states like Georgia and Texas last year, the number of competitive congressional and state legislative seats plunged. In Texas, the number of safe GOP House districts will increase from 17 to 23, according to the Cook Political Report, while the number of competitive districts will fall from 12 to just one. Despite being one of the most competitive states in 2020, Georgia will have almost no swing districts in the state legislature and no competitive congressional districts—the closest GOP-held House seat has an 8-point Republican advantage. (Democrats and voting rights groups have filed suit against these maps.)

That means that GOP legislators not only can ignore the views of a majority of voters, but in deep-red districts they’ll be chiefly concerned with primary challenges, accelerating the party’s radicalization against democracy. “They’re going to have more Marjorie Taylor Greenes in their caucus,” says Michael Li, an expert on redistricting at the Brennan Center for Justice.

This is how Trump’s end goal for January 6 becomes far more likely in 2024: If Republicans take back the House through aggressive gerrymandering, they’ll not only derail Biden’s agenda, but they’ll be much more inclined to reject the results of a contested presidential election if a Democrat wins. Sixty-five percent of House Republicans refused to certify the election results in 2020 just hours after the insurrection, and that caucus will become even more radical after 2022.

“The people who don’t want to certify free and fair elections,” predicts Rep. Mondaire Jones (D-N.Y.), “will regain control of the federal government. They will make it harder for representative government to ever exist moving forward.”

While Republicans have been hellbent on subverting American democracy, Democrats have been slow to properly defend it.

Biden didn’t give a major speech about voting rights until July in Philadelphia. By then, 18 states had already passed laws making it harder to vote and Texas Democrats had fled to DC in a Hail Mary effort to block a sweeping voter-suppression law. Though Biden deemed “the assault on free and fair elections” to be “the most significant test of our democracy since the Civil War,” for the better part of a year his administration did not treat this threat to democracy as an existential emergency. Biden called passage of voting rights legislation “a national imperative,” but never mentioned the filibuster that was blocking such legislation or laid out a plan to overcome it.

Indeed, a remarkable asymmetry in tactics has defined this fight. While Republicans have made the hostile takeover of the country’s election system their central organizing principle, the Biden administration prioritized economic legislation over voting rights, going so far as to list the passage of the infrastructure bill as the first item in a fact sheet touting the steps it had taken to “restore and strengthen American democracy” ahead of a global democracy summit in December. Biden believed that passing popular pieces of legislation would “prove democracy works” and restore the public’s faith in the democratic process, but the administration’s focus on economic policy—and its pursuit of bipartisanship—failed to blunt the growing radicalization of the GOP.

GOP-controlled states have passed new voter-suppression laws, gerrymandered maps, and election-subversion bills through simple majority, party-line votes. Yet recalcitrant centrist Democratic Sens. Joe Manchin (W.Va.) and Kyrsten Sinema (Ariz.) have insisted that any federal legislation stopping such measures requires a bipartisan supermajority, portraying the filibuster not as an impediment to protecting democracy, but as integral to its functioning.

It’s a situation that evokes the end of Reconstruction. Back then, insurrectionist Democrats (then the party of white supremacy) used every means necessary—including violence and vote-rigging—to retake control of the state and federal governments, while accommodationist Republicans (then the party of civil rights) appealed to bipartisan unity, touted economic legislation, and supported the filibuster to block voting rights legislation, leading to nearly a century of Jim Crow.

Finally, in the past couple of weeks, Democrats have made a last-ditch push to protect voting rights, with Biden saying he supports exempting voting rights bills from the filibuster, and Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (N.Y.) pressing hard to change the Senate rules to overcome GOP obstruction, setting up a showdown on the filibuster by Martin Luther King Jr. Day. “Today I’m making it clear: to protect our democracy, I support changing the Senate rules, whichever way they need to be changed, to prevent a minority of senators from blocking action on voting rights,” Biden said during his speech in Atlanta this week. “When it comes to protecting majority rule in America, the majority should rule in the United States Senate.” If Democrats do manage to persuade Manchin and Sinema—pretty unlikely—to quickly approve approve new bills banning partisan gerrymandering and expanding voting access, such as the Freedom to Vote Act and John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, it will go a long way toward stopping GOP efforts to undermine democracy. But time is running out for it to have much impact on the midterms.

Most key battleground states have already passed new redistricting maps that courts could be reluctant to alter in the thick of an election year—and, though many states quickly expanded voting options during the pandemic in 2020, it takes time to properly implement pro-voter policies like online and automatic registration. As Li notes, “Congress is in danger of losing the 2022 election cycle” to anti-democratic forces.

Republicans who falsely maintain that the election was stolen say they are extremely motivated to vote in 2022, with the Big Lie functioning as a new Lost Cause movement, similar to how embittered Southerners used the death of the Confederacy as a rallying cry to fuel the backlash to Reconstruction. At the same time, the blockage of voting rights legislation is demoralizing the Democratic base—which views democracy protection as a pressing priority—and threatening to depress turnout, making it easier for Republicans to prevail in the midterms and advance their assault on democracy.

For months, voting rights advocates and scholars of democracy have issued hair-on-fire warnings about the danger that the GOP’s death-by-a-thousand-cuts strategy poses to the very foundation of representative democracy. “The American experiment is at risk,” Holder says. This is not hyperbole. And by 2024 the damage may have already been done. The members of Congress, governors, secretaries of state, attorneys general, state legislators, and local officials elected this November will determine to a large extent whether there will be fair elections for years to come.