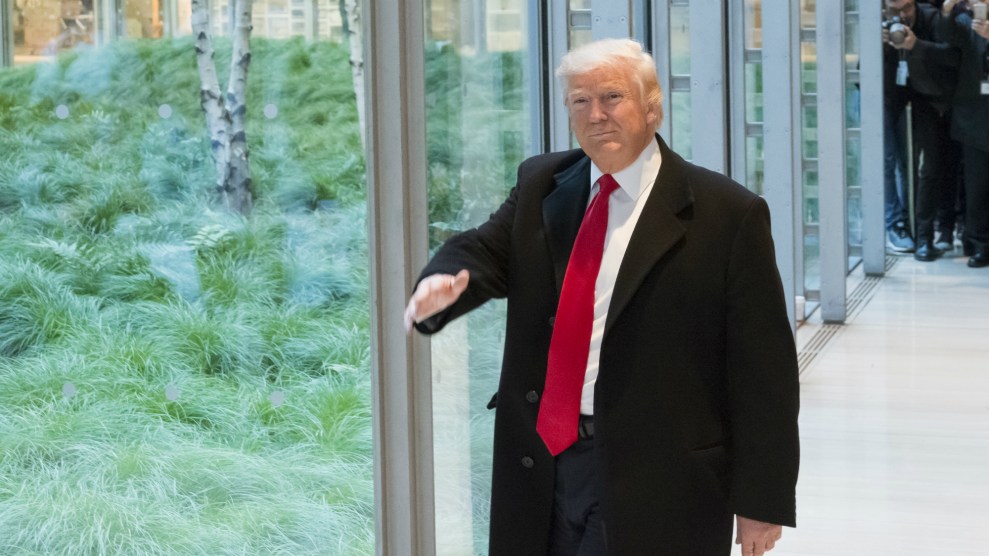

Pablo Martinez Monsivais/AP

Unless something drastic changes, Donald Trump, the self-proclaimed “King of Debt,” will enter the White House on January 20 with about $713 million in debt. He carries mortgages for all his prized properties—including Trump Tower, the Doral golf course in Miami, and his swanky new Washington, DC, hotel—and this does not count another $2 billion in debt (including massive loans from the state-owned Bank of China) that finances partnerships in which he participates.

These loans create significant conflicts of interest. For instance, his biggest lender, Deutsche Bank, is in the middle of negotiations with the Justice Department over how many billions of dollars in civil penalties it should pay for its role in the 2008 financial crisis. Yet as Trump has recently tweeted, the celebrity mogul has no plans to sell his mortgaged assets. Instead, he says, he will let his adult children manage his business and deal with these properties. (Trump postponed a press conference scheduled for this week in which he was supposed to unveil the details of his plan for separating himself from his business empire.) But according to ethics experts, divestiture is the only way Trump can truly address the conflicts.

As Trump has pointed out, there is no law that requires him to sell these assets. But since the 1970s, presidents have taken steps to minimize their conflicts of interest—even if only to avoid the appearance of a conflict. One good example for Trump: President Barack Obama. In 2013, as home mortgage interest rates plummeted, Obama publicly urged Americans to take advantage of the falling rates and save themselves a bundle of money. Alas, Obama told a town hall audience in 2013, he couldn’t follow his own good advice.

“Well, not to get too personal, but our home back in Chicago—not the White House, which, as I said, that’s a rental—our home back in Chicago, my mortgage interest rate, I would probably benefit from refinancing right now, I would save some money,” Obama said. “When you’re President, you have to be a little careful about these transactions, so we haven’t refinanced.”

Be careful—by that, Obama meant he did not want to get close to a conflict of interest by negotiating a deal with any bank. And that entailed a personal sacrifice.

Obama’s mortgage, which he took out in 2005, carries a 5.62 percent interest rate—significantly higher than the current rates that are around 4 percent for a 30-year mortgage. In 2015, USA Today estimated that Obama could save almost $2,100 a month by refinancing. But though he was not prevented from taking advantage of the lower rates, he chose not to do so. He had learned his lesson. Years earlier, when he first entered office, his 5.62 percent mortgage was heavily scrutinized, with the question being whether he had received a below-market rate as an act of favoritism. A Federal Election Commission investigation determined that Obama had obtained a discounted rate but that it was legal because it was within the range offered by Obama’s bank to customers who may provide the bank with additional business.

Before entering the White House, Obama sold his stock portfolio and invested all his personal assets in Treasury notes with some smaller investments in broadly held mutual funds. Once again, he was not compelled to do this by any law—federal conflict-of-interest laws and rules do not apply to the president—but he took this step to remove any taint of possible conflict.

So far, Trump is taking a different approach. He says he has sold off his stocks—without offering any documents to confirm this. But he has not publicly addressed the conflicts posed by his massive borrowing or by his connections to his family business. His transition team now says he will hold a press conference in January to present his plan to deal with potential business conflicts. Yet he certainly has not yet met the standard followed by the man he is succeeding.