<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/unitedsoybean/9621039035/sizes/z/in/photolist-fEbkHn-gjXoFZ-fEacJe-fEhApK-fEbkaV-fEtaFw-fE9o5g-fErMdd-fEb9xr-fErMh5-fEsVN1-fEzaVs-fEhABH-fEzbCW-gjXppx-gjXCfU-fEhAfx-gjYFYn-fEb9i6-gjYz87-fEzaMf-ayW5R7-at3YXQ-8SiCsR-ceGBB3-8fcFCA-8fcFCE-aYHpMT-8SyFAw-8SmBgs-gs3UB8-gs3r2C-gs3sKs-gs364b-gs4gjb-gs4dw4-gs4f5z-gs4xfg-gs3Yuu-gs4d5T-gs3ZWr-gs4uJK-gs3X2u-gs4bxV-gs3ZKL-gs49by-gs3Hgn-gs41GA-gs3RpB-gs3Gex-gs35Nb/">United Soybean Board</a>/Flickr

Argentina’s agricultural transformation over the past 20 years—from prime producer of grass-finished beef to one of the globe’s genetically modified crop-producing powerhouses—is often hailed as a triumph of high-tech ag. Starting in the 1970s and accelerating recently, high crop prices and various government policies inspired ranchers in the fertile Pampas and Chaco regions to plow up pasture—releasing large amounts to carbon in the process—to plant soybeans, mainly for export markets. In the mid-1990s, when Monsanto rolled out its soybean seeds engineered to resist herbicide, Argentina’s new crop farmers were early adapters (see chart to the right).

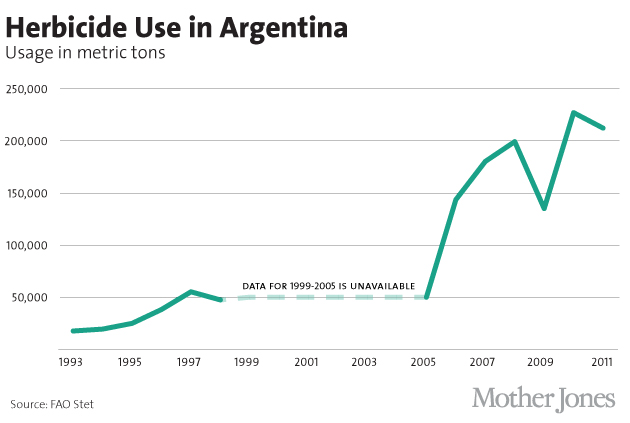

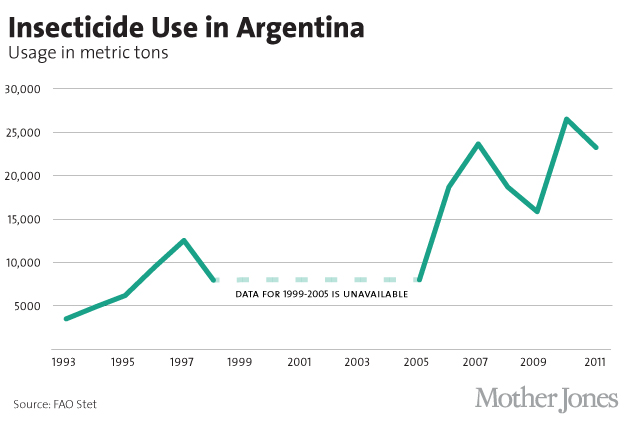

Today, Argentina is the globe’s third-largest soy producer—and nearly 100 percent of its soy crop is genetically altered. The trend has certainly benefited the GMO seed and agrichemical industry—as the below charts show, herbicide, pesticide, and fertilizer use has soared over the past 15 years.

But what about the people who live in the country’s agricultural regions? A recent article by Associated Press reporters Michael Warren and Natacha Pisarenko paints a grim picture of life in the farm belt in the age of industrial corn and soy:

In Santa Fe, cancer rates are two times to four times higher than the national average. In Chaco, birth defects quadrupled in the decade after biotechnology dramatically expanded farming in Argentina.

The story quotes a pediatrician and neonatologist names Medardo Avila Vazquez, who has been moved to found a group called Doctors of Fumigated Towns. “We’ve gone from a pretty healthy population to one with a high rate of cancer, birth defects, and illnesses seldom seen before,” he tells Warren and Pisarenko.

GMO seed giant Monsanto—whose soybean and corn seeds engineered to withstand its own herbicide, Roundup (glyphosate), blanket the nation’s farmland—denies responsibility for the possible link between agrichemicals and rising rates of health disorders, the AP writers report. The company “does not condone the misuse of pesticides or the violation of any pesticide law, regulation, or court ruling,” A Monsanto spokesperson told Warren and Pisarenko.

Even so, Warren and Pisarenko found pesticide use to be at best lightly regulated. “With soybeans selling for about $500 a ton, growers plant wherever they can, often disregarding Monsanto’s guidelines and provincial law by spraying with no advance warning, and even in windy conditions,” they write.

Meanwhile, provincial restrictions against spraying too close to residential areas are often honored in the breach. The AP story features multiple accounts of people coming into direct contact with agrichemical sprays—just because they lived near farm fields. In one town, teachers reported students getting doused by chemical sprayers during class. In another, a government study found pesticide traces in the blood of 80 percent of children.

The authors make clear that one major driver of Argentina’s surging herbicide use is that weeds there have developed resistance to Monsanto’s flagship herbicide, Roundup. Just as they’ve done in the US, farmers there have responded by jacking up their doses of Roundup and adding “much more toxic poisons, such as 2,4,D, which the US military used in ‘Agent Orange’ to defoliate jungles during the Vietnam War.”

Even Roundup’s reputation as a relatively benign agrichemical has come under fire from Argentine researchers alarmed at the effect this chemical deluge might be having on people. In a 2010 paper, a research team led by the University of Buenos Aires professor Andrés E. Carrasco found that “injecting a very low dose of glyphosate [Roundup’s active ingredient] into embryos can change levels of retinoic acid, causing the same sort of spinal defects in frogs and chickens that doctors increasingly are registering in communities where farm chemicals are ubiquitous,” Warren and Pisarenko report. Monsanto disputes the study’s findings, claiming they were undermined by flawed methodology and “unrealistic exposure scenarios.”

Meanwhile, the epidemiological evidence—health assessments of people living near chemical-intensive farms—is unsettling. In the Chaco region, a study of 2,051 people in six towns found “significantly more diseases and defects in villages surrounded by industrial agriculture than in those surrounded by cattle ranches,” the AP reports. “In Avia Terai, 31 percent said a family member had cancer in the past 10 years, compared with 3 percent in the ranching village of Charadai.”

It’s worth noting that that Argentina’s Pampas region—another place where both chemical use and rates of cancer and birth defects have risen—is widely known for its highly productive form of traditional agriculture, which produces top-quality grass-finished meat and a surplus of grain as well. Michael Pollan described it in his famous 2009 essay “Farmer-in-Chief”:

There, in a geography roughly comparable to that of the American farm belt, farmers have traditionally employed an ingenious eight-year rotation of perennial pasture and annual crops: after five years grazing cattle on pasture (and producing the world’s best beef), farmers can then grow three years of grain without applying any fossil-fuel fertilizer. Or, for that matter, many pesticides: the weeds that afflict pasture can’t survive the years of tillage, and the weeds of row crops don’t survive the years of grazing, making herbicides all but unnecessary.

Pollan even held up the Pampas system as a model for reforming our own chemically ravenous agriculture: “There is no reason—save current policy and custom—that American farmers couldn’t grow both high-quality grain and grass-fed beef under such a regime through much of the Midwest.”

But he added, presciently, that “today’s sky-high grain prices are causing many Argentine farmers to abandon their rotation to grow grain and soybeans exclusively, an environmental disaster in the making.”