Over the past four decades, private equity has become a powerful, and malignant, force in our daily lives. In our May+June 2022 issue, Mother Jones investigates the vulture capitalists chewing up and spitting out American businesses, the politicians enabling them, and the everyday people fighting back. Find the full package here.

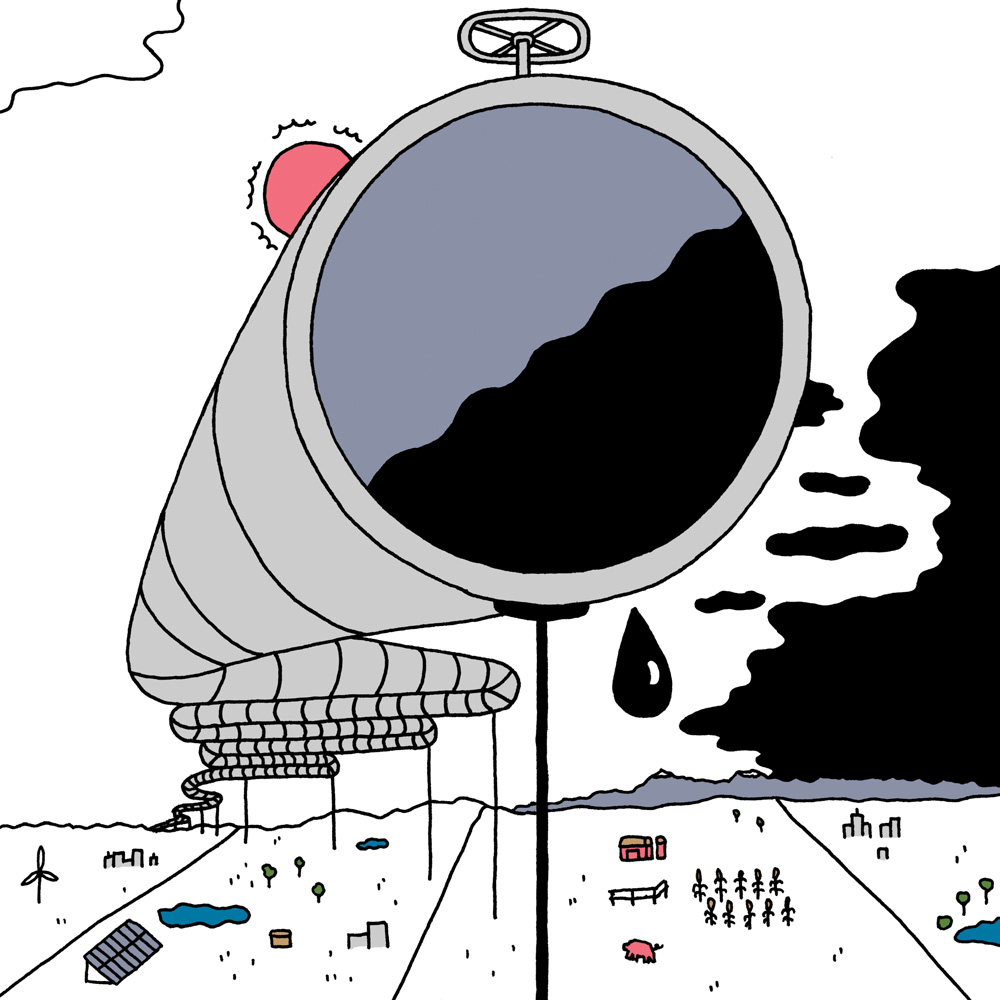

For most of his 30-year career, Iowa farmer Dan Wahl never knocked heads with his state’s agribusiness goliaths. He was too busy tending his crops and cattle on 640 acres of land. But then, in September 2021, a subsidiary of a private equity firm called Summit Agricultural Group started mailing packets to farmers in his area, pitching its plan to build a 2,000-mile pipeline through 30 Iowa counties as a way of breathing new life into the state’s troubled ethanol industry. The pipeline, dubbed the Midwest Carbon Express, would slash across Wahl’s farm on its way to grab carbon dioxide generated by 31 corn ethanol plants in five states. It would carry the CO2 to North Dakota, where the gas would be buried underground. By burying ethanol’s carbon waste, the project would make the fuel more climate-friendly, and by bolstering the ethanol trade, it would boost the price of corn, benefiting the state’s farmers, the pitch goes.

Wahl didn’t take the idea seriously at first. But then he heard from some neighbors that Summit was prepared to appeal to the Iowa Utilities Board to seize any land not ceded through voluntary easement. That suddenly sounded to Wahl like a credible threat. After all, Summit’s founder and CEO, Bruce Rastetter, is a heavyweight in Iowa politics with close ties to the state’s past and current governors who have appointed members of that very board.

An agribusiness magnate, Rastetter has deftly leveraged his wealth to gain political influence. His generous campaign donations to and chummy relations with his home state’s GOP power structure inspired Politico to deem him the “real Iowa kingmaker.” Now he’s making what could be his biggest play yet. Summit’s Midwest Carbon Express project would take advantage of federal tax credits meant to mitigate climate change—and it is poised to net him and his investors a massive windfall.

Rastetter frames the Midwest Carbon Express as the key to establishing ethanol as a green fuel for the carbon-constrained future. But many environmentalists and academic researchers are appalled by the idea, insisting that the pipeline system would further entrench an industry that has promoted unsustainable agriculture and yielded few climate benefits.

And the pipeline has sparked a battle over land rights. In January, Summit applied to the Iowa Utilities Board for a pipeline permit, which, if granted, will automatically trigger eminent domain for land not acquired by agreement with owners. Hundreds of landowners in the pipeline’s path are refusing to cede right of way. “I bought and paid for this [land], and I’ll be damned if you’re gonna take it from me,” Wahl remembers thinking when he learned about Summit’s project. He has since joined a grassroots resistance movement that has prompted commissioners in 15 counties to urge Iowa’s utility board to deny eminent domain.

But the potential profits from carbon capture projects are so great that, despite public opposition and scientific outcry, proposals to build out CO2 pipelines are multiplying. Last year, Texas-based oil refiner Valero and the private equity arm of BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, announced their intention to fund a 1,300-mile pipeline dubbed the Heartland Greenway. In January, Archer Daniels Midland, the Illinois-based grain-trading giant and ethanol producer, jumped into the fray, rolling out plans for a 350-mile pipeline to be built and run by Canadian energy-infrastructure titan Wolf Midstream. ADM’s lobbying efforts in the 1970s and ’80s helped spur the US ethanol industry into existence. Now it’s going to clean up on cleaning up ethanol.

Private equity players are “always looking for opportunities to burnish their image” with an environmental claim, says Alyssa Giachino, research director at the watchdog group Private Equity Stakeholder Project. “If they see it penciling out through any combination of tax credits or subsidies or market opportunities, they’ll go for it.” The risk, she argues, is that they’ll use public resources to cash in on “questionable technologies that end up cloaking the role” that industries like oil and ethanol play in driving climate change.

The business model for Rastetter’s Midwest Carbon Express hinges on an obscure subsidy for carbon sequestration. Remember “clean coal”? That was the idea, popular in the aughts among politicians of both major parties, that burning coal for electricity could be made environmentally benign simply by capturing its carbon dioxide emissions and piping them deep underground. In 2008, at the height of euphoria around the technology, Congress created a provision called 45Q, which delivered a tax credit for every metric ton of carbon that any emitting company managed to sequester.

Clean coal turned out to be a bust—but 45Q stayed in the tax code. A bill signed into into law by Donald Trump boosted its value. President Joe Biden has backed legislation that would deliver an additional 70 percent jump in the value of the 45Q tax credit—a policy championed by Sen. Joe Manchin (D-Coal Country), giving it a strong chance of passing in a gridlocked Senate.

Summit claims its Midwest Carbon Express will be able to sequester as much as 12 million metric tons of CO2 annually. That means the company could expect up to $600 million in annual credits from 45Q alone—$7.2 billion over 12 years.That’s more than enough to pay off the $4.5 billion needed to build the pipeline. Summit execs are not shy about how much the Midwest Carbon Express relies on 45Q for profitability. “The $50 a ton really covers the majority of that capital expenditure,” Jim Pirolli, chief commercial officer for Summit Carbon Solutions—the subsidiary building the pipeline—said at the American Coalition for Ethanol’s annual meeting last August. Summit won’t divulge investors in the project, but private equity firm Tiger Infrastructure Partners and farm-equipment giant John Deere have both jumped in, Bloomberg Law reported. In early March, oil-and-gas titan Continental Resources announced it would invest $250 million; the company’s founder and chair, billionaire Harold Hamm, is a former Trump ally who proudly calls himself an “oilcrat.”

Continental’s investment points to another perverse incentive. Before the CO2 captured at the ethanol plants is buried under the earth, the pipeline could detour it to petroleum companies, which would inject the gas down into nearly spent fracking wells to force the last bit of crude up to the surface. The 45Q credit pays a bit less overall for this “enhanced oil recovery.” But if crude oil becomes pricey enough, petroleum companies will be tempted to pay a lot for the CO2 to wring as much as possible from flagging wells, sweetening the deal overall. If Summit keeps its promise to harvest and immediately sequester 12 million metric tons of carbon a year, it would generate $600 million in annual 45Q credits. Or it could team up with oil companies and make some $850 million total (assuming oil trades around $100 per barrel). A company spokesperson wrote that the project is “designed solely to capture and permanently sequester carbon dioxide,” and that enhanced oil recovery “isn’t even an option.” Still, “it’s very unlikely that private equity would be able to walk away from a deal like that,” Giachino says.

Summit insists that it doesn’t intend to use the carbon it captures for oil extraction. But as a Summit exec said in a meeting with landowners in September 2021 in Ames, “We want to keep all of our options available.” And Summit has chosen to place its sequestration site hundreds of miles away from Iowa’s cluster of ethanol plants, in an area of North Dakota not far from the potentially oil-rich Bakken Formation. Continental Resources claims to be the “largest leaseholder and the largest [oil and gas] producer” in the region.

The prospect of handing Summit and its pipeline peers bags of money to help Big Oil extract more fossil fuels isn’t the only environmental liability hanging over the pipeline projects, critics say: The ethanol itself makes it suspect.

Summit is claiming its pipeline is crucial to keeping “corn production, and our way of life, viable long into the future,” as Pirolli told attendees at a Des Moines land-investment conference in January. By burying their carbon dioxide, affiliated ethanol plants will be eligible for lucrative payouts through state programs like California’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard, a program that credits makers of low-carbon fuels. The credits can be sold to polluters needing to meet those states’ requirements for lower emissions. Summit says it would split the credits, potentially worth billions of dollars on top of the 45Q windfall, with the ethanol plants that participate in the pipeline. At the January pitch to investors, Pirolli said a typical ethanol plant could expect to receive between $12 million and $15 million annually from low-carbon fuel programs.

But continuing to prop up ethanol is an environmental dead end, says Jason Hill, an engineering professor at the University of Minnesota. The Renewable Fuel Standard obligates fuel producers to cut the nation’s gasoline supply each year with 15 billion gallons of ethanol, reducing gas consumption by about 6.7 percent. By displacing a fraction of petroleum, this heavily subsidized ethanol makes conventional gasoline cheaper—incentivizing people to drive more and to buy less-fuel-efficient vehicles. As a result, Hill and two colleagues found in a 2016 paper, the net effect was to increase cars’ greenhouse gas emissions by about 22 million metric tons of carbon dioxide annually, the output of nearly six coal-fired power plants. Hill’s research has shown that merely boosting the average mileage of the US car fleet by two miles per gallon would offset more gasoline use every year than the current level of ethanol production does.

A 2022 paper by a team of researchers led by the University of Wisconsin’s Tyler Lark came to a similar conclusion to Hill’s. They found that “carbon intensity of corn ethanol” produced under the US mandate is “no less than gasoline and likely at least 24 percent higher.”

Jonathan Foley, an environmental scientist and the executive director of Project Drawdown, a climate think tank, says thinks federal subsidies for sequestering carbon from ethanol would be much better spent speeding up the electrification of transportation and the building out of green energy sources like wind and solar power. “We could have more efficient cars and more electric vehicles for a lot less money.”

But why turn to electric cars when your entire career path has hinged on turning corn into gold? After hog farming made Summit CEO Bruce Rastetter rich, in 2003 he pivoted and founded a startup called Hawkeye Holdings and its subsidiary Hawkeye Renewables to produce ethanol. He had his finger in the prevailing wind: By 2005, President George W. Bush had signed a bipartisan energy law that effectively mandated a dramatic ramp-up in corn ethanol production. Within months, Rastetter sold an 80 percent stake in Hawkeye Holdings to a New York private equity firm, Thomas H. Lee Partners, for $312 million. The ethanol industry soon plunged into crisis because of oversupply, and Hawkeye Renewables ended up going bankrupt, but Rastetter had already cashed out.

In 2010, he founded Summit, which has snapped up more than 50,000 acres of Midwestern farmland. Again, excellent timing: Adjusted for inflation, the average price of an acre of Iowa ground rose more than 60 percent between 2010 and 2020.

When Rastetter launched the division overseeing Summit’s pipeline project in 2021, he quickly flexed his political influence. He hired his longtime ally Terry Branstad, Iowa’s governor for 22 years, as its senior policy adviser. With the eminent domain fight gaining momentum, the Branstad connection could become crucial: The former governor appointed two of the three members on the Iowa Utilities Board, which will ultimately decide the case. Current Gov. Kim Reynolds, a major recipient of Rastetter’s campaign donations, appointed the other one. In January 2022, Rastetter hired Jess Vilsack, son of Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack, for the role of general counsel. The elder Vilsack is a fervent ethanol champion who served as Iowa’s governor 1998 to 2007, during which time Rastetter gifted $15,250 to his campaigns.

The USDA doesn’t oversee the 45Q program, but Rastetter has allies who will likely serve in the federal agency that does: the Department of Energy. In September 2021, President Biden nominated Brad Crabtree, then director of the Carbon Capture Coalition, to be the DOE’s assistant secretary for fossil energy and carbon management. The Senate approved the appointment on April 28. The Carbon Capture Coalition calls itself a “collaboration of more than 100 companies, unions, conservation and environmental policy organizations.” Its members include Summit Carbon Solutions, Archer Daniels Midland, Valero—all of which have carbon pipelines in the works—as well as fossil fuel giants Shell and Peabody. The bipartisan Infrastructure bill signed into law in November 2021 devotes billions of dollars worth of loans and grants, to be administered by the DOE, to the very kind of carbon-capture and storage projects proposed by Summit and its pipeline peers. In a January 22 statement, the Carbon Capture Coalition hailed the law as the “single largest investment in carbon management provisions in history.”

Meanwhile, In Iowa, opposition to the pipeline is mounting. As of mid-April, landowners had voluntarily ceded just 20 percent of territory in the pipeline’s path to the company, Reuters’ Leah Douglas reported. For their part, aysaying landowners have contracted attorney Brian Jorde, who led the ultimately successful fight to block the Keystone XL pipeline in Nebraska, to represent them. They have also joined forces with the Sierra Club to fight the project. “Our leverage is that our coalition is so diverse—it’s made up of people who’ve been told for a long time that we’re supposed to hate each other,” says Jessica Mazour, a Sierra Club organizer who’s helping galvanize the anti-pipeline push. “And that shows us that this isn’t a Republican or Democrat thing—it’s a right or a wrong thing.”

Dan Wahl, the farmer now raising hell to stop Summit from slicing through his farm, questions how regular Iowans will benefit from a project designed to enrich powerful corporations at the expense of the climate: “It’s like it’s the biggest welfare program for the wealthiest people in the world.”