This story was produced in collaboration with The Marshall Project. You can sign up for their newsletter here.

Chuck Coma tried to lie still in his hospital bed. But there was a spasm in his chest, like something inside was fighting to get out.

“It says here you had an injury in 2016, and you’ve been jerking since then. Are there any triggers?” the technician asked, wrapping a tape measure around his head and marking it with a red Sharpie.

“No, it just happens.”

Chuck was in yet another doctor’s office, this time the neurology department of the Veterans Affairs hospital in Seattle, Washington. It had been nearly eight months since he came home from federal prison, after serving roughly 15 years for armed bank robbery. And it had been 3 years, 5 months, and 25 days since “the incident” inside that made his life as a free man not so free after all.

Since his release, Chuck’s time had mostly been spent sitting next to his 77-year-old mother, Donna, in hospital waiting rooms; being prodded and quizzed by specialists; searching for answers and coming up empty. This appointment was for an electroencephalogram, a test they hoped would explain why, ever since his traumatic brain injury, Chuck couldn’t stop shaking.

Chuck often joked about the condition that had hijacked his life. “It’s a positive vibration,” he’d say. That’s why Donna joined him for every exam, to correct his understated version of their daily struggle. Right after nurses dropped him at her house in Shelton, Washington, with a pile of pill bottles and a sheet of instructions, he often shook so badly he couldn’t feed himself. Some days he simply sat in the bathtub for hours, praying for it to stop.

Donna filmed those moments on the smartphone she barely knew how to use, to show his doctors and lawyers what prison had really done to her son. On his worst days, she was the one who had to pour his pills down his throat and fix his bowl of cereal. She had also been the one to fill in the years of missing memories and weather his angry outbursts. But those were conversations for different doctors at different appointments.

“We’re going to take a look at your brain waves,” the technician said. “A seizure is an abnormal discharge of energy.”

“If my seizures are so light, maybe I don’t need meds and maybe my brain will repair itself?” Chuck asked. “Some doctor told me once when you have dead brain matter, it’s dead. You can’t fix it.” The tremors were slowing down a bit lately. Chuck hoped that meant he could someday move out of his mother’s house, buy a motor home, and road trip his way across the country.

“I don’t know about repair itself, but the doctors can make decisions about medication,” the technician said, watching the blue and red lines of Chuck’s brain waves jump across her computer screen. “Eyes open,” she instructed again and again, her voice tolling like a metronome in an otherwise quiet room. “Eyes closed.”

Donna leaned in and rested her chin on her fist, staring at the electrodes streaming from her son’s head. This Chuck was a diminished version of her “Charlie Brown,” the man who had jumped out of helicopters in two foreign wars, hauled in thousands of pounds of Alaskan crab on Bering Sea fishing boats, and scuba-dived off the Washington coast without a license. But that was before prison, before “the incident,” before she became a full-time caretaker for her 51-year-old son. She hoped this test would tell her—would it always be this way?

“Eyes open. Eyes closed.”

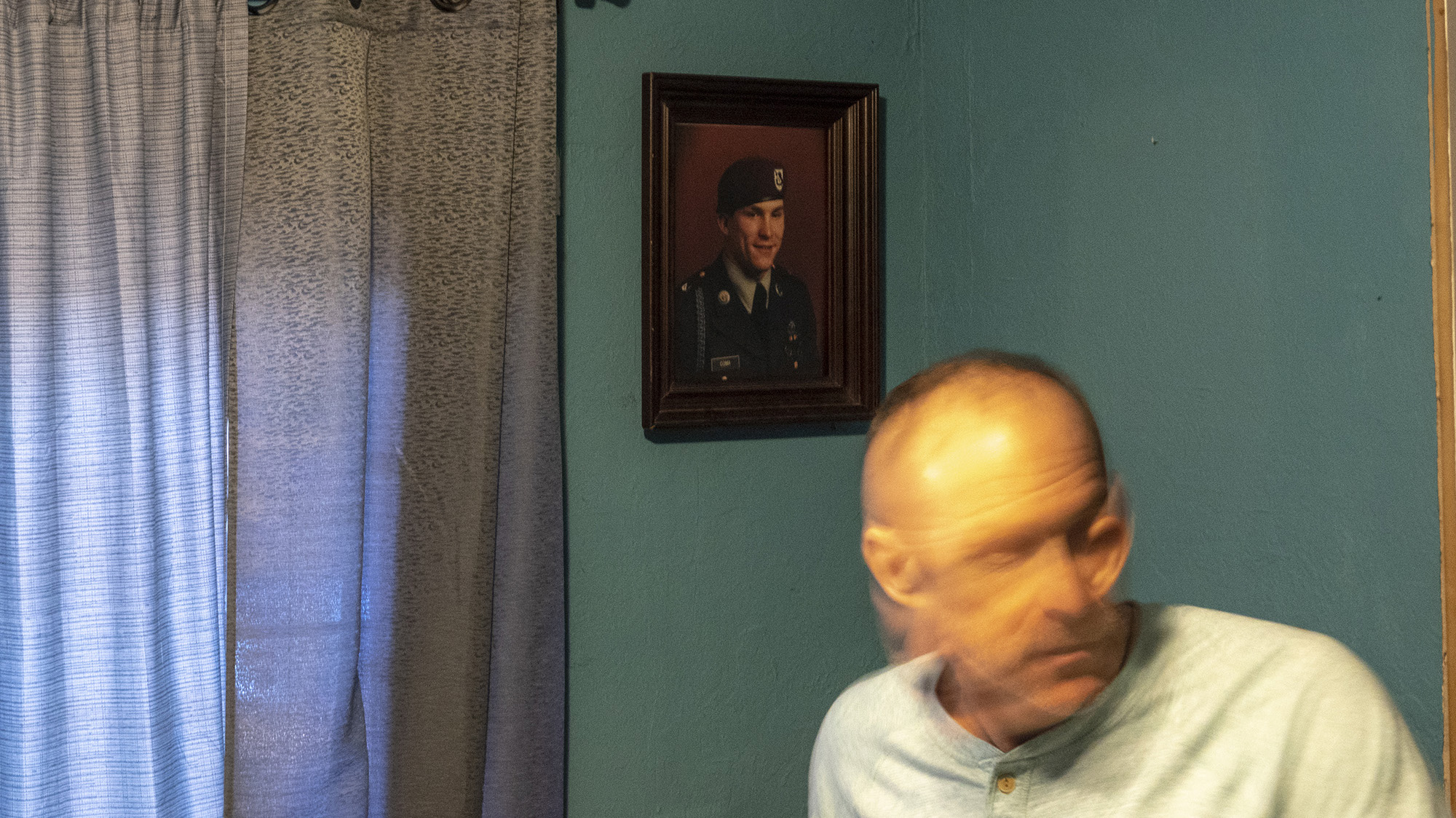

Chuck and Donna Coma in Donna’s kitchen.

Peter van Agtmael/Magnum Photos

Chuck Coma wrote down information while trying to reach his psychiatrist at the Veterans Affairs hospital. Chuck was hoping to be prescribed medication to reduce his tremors, which had disrupted his life ever since he returned from prison.

Peter van Agtmael/Magnum Photos

It was a foggy Saturday morning in February 2016 when Donna got the call. The caller ID said Lewisburg, Pennsylvania—a small town nearly 3,000 miles from her home on the Olympic Peninsula. Lewisburg was where Chuck was locked up. But when he called for their 15-minute, $3.75 conversations several times a week, it always appeared as a blocked number.

Donna muted the chatter of morning TV and settled into her recliner. Her living room walls were covered with pictures of her kids and grandkids, including a black-and-white portrait of toddler-aged Chuck holding a baseball.

On the line was the chaplain from Lewisburg Penitentiary. He asked if this was Mrs. Coma, mother of Charles Coma.

“Yes,” she said.

“There was an incident,” the chaplain told her. He didn’t know if Chuck would live through the night.

Donna erupted: “When? What happened? How is he?”

“I’m sorry,” he told her. “That’s all I can say.”

That he called at all was a sign of Chuck’s grave condition. Families are rarely notified of the everyday acts of violence—fights, stabbings, and macings—at a prison like Lewisburg.

Donna knew her son had been healthy, running laps around the prison yard and practicing karate in his cell. And with only a couple years left in his sentence, she couldn’t imagine he would try to hurt himself.

After two days with no information, Donna managed to reach a counselor at the prison. Her daughter, Tracey, and son-in-law, Chris, came over to listen in on speakerphone. Chuck’s heart had briefly stopped, the counselor told them, but he had been revived and moved to an outside hospital. It appeared to be a suicide attempt.

The family yelled in disbelief; Tracey called him a liar. If Chuck died, Donna told him, “You do not cremate him, you better send him home. I want to know what really happened.”

Twelve days later, Chuck woke up.

He was in the intensive care unit with prison guards at his bedside and a breathing tube in his throat. One of his first visitors was a special investigative agent from the federal Bureau of Prisons. The agent asked Chuck if his cellmate assaulted him. Chuck tried to speak but no sound emerged. After a long pause, he mouthed “yes.”

Chuck Coma takes a regimen of pills daily to help mitigate the effects of his near-deadly assault in prison and the PTSD from his combat experience.

Peter van Agtmael/Magnum Photos

Chuck Coma in his mother’s kitchen.

Peter van Agtmael/Magnum Photos

Growing up on the Washington coast, Chuck had learned to operate commercial fishing equipment before most people get their learner’s permit. By 15, he was working on a family friend’s Alaskan shrimping boat, just like his father and older brother, Rick. “He was a … cocky go-getter,” his boss later wrote to a judge. Chuck was a short kid but muscled and scrappy, often getting into fights at school. Even as a brash teen, he was affectionate with his mother, slinging his arm around her when they ran errands. He called her “my best girl.”

By the end of high school, he was partying and acting out, like when he and his friends slashed the tires of a big-rig truck. (Chuck took the fall.) Donna was usually the family disciplinarian, but this time his father, Gary, a 6’ 4’’ Vietnam veteran, told Chuck he had two options in life: Enlist in the Army or end up in jail.

In December 1989, soon after he completed training, Chuck helicoptered into Panama amid a barrage of gunfire as part of an operation to oust the country’s dictator, Gen. Manuel Noriega. Two men in his unit, one only 18 years old, were killed by a grenade. Soon after returning from Panama, he was deployed to the Persian Gulf for Operation Desert Storm. Though he faced less frequent gunfire, he had to worry whether chemical weapons were forever altering his brain.

Chuck in the Persian Gulf War.

Courtesy Chuck Coma

Chuck came home in 1991, bringing with him a leather jacket he said was Noriega’s, an album with washed-out photos from the Iraqi desert, and a reel of violent images he couldn’t scrub from his mind. He developed a mysterious rash across the bottom half of his body and frequent, sharp pains in his gut.

Chuck briefly returned to fishing, getting a job on a boat called the “Rogue” alongside his brother, Rick. But memories of the gunfire, of the 18-year-old who didn’t make it, kept pulling him under.

In the sleeping cabin at night, Chuck often woke up screaming in his bunk. But when Rick asked about his nightmares, he shut down. Chuck left the job after a few months, telling the captain he needed to work out some problems in his head. Back on land, Chuck eventually moved in with his mother. She bounced between jobs, ultimately opening up her own beauty shop.

Chuck’s decline was familiar to Donna. She remembered waking up in a headlock as her husband Gary screamed about his memories from Vietnam. He, too, had stopped fishing because he couldn’t stand being confined in a cabin. Donna watched Gary self-medicate through drinking. Now Chuck was also burying his memories in alcohol, cocaine, and whatever else he could get his hands on.

Chuck started racking up a criminal record—DUIs, drug possession, assault. One day, he came to Donna’s salon for a haircut. When several cop cars pulled up out front, Chuck climbed out the back window with half-cut hair and the salon cape still tied around his neck.

In September 2000, Chuck plotted his wildest crime yet. He put on a blonde wig and walked into a bank, sliding the teller a note that said “no alarms … quickly and quietly.” Then he drove to another bank and did it again. Police chased down his bright green Jeep after he pulled a U-turn through the highway median. A bag with $2,344 was sitting on the front seat.

Looking back, he can’t quite make sense of it. Maybe he saw some romance in the idea of being a bandit—the audacity of it. “There might have been a sick part of me that thought I was just going to go around the country robbing banks,” Chuck said. “Wishful thinking, huh?”

At sentencing, Chuck’s attorney stressed that his criminal record began only after he returned from war—the violence he witnessed abroad begot violence at home. A federal judge gave him three years in prison and three years of probation after that. But if anything, his stint inside made him even more reckless.

In 2004, less than a year after he got out, Chuck put on a long black overcoat, wrapped his face in Ace bandages, and grabbed his rifle. He walked into a bank in Olympia, pointed the gun at the teller’s face, and demanded she hand over the cash. Chuck shoved the money in a backpack, dropping wads on the floor, and fled. As he tore out of a nearby parking lot, sirens wailed behind him. He didn’t stop until he crashed through a chain-link fence blocking an inlet of Puget Sound.

Chuck emerged from his car in a full scuba suit and headed toward the water, carrying a diving tank and his backpack of cash. As he threw the bag into the ocean, an officer tackled him on the shore. Several more cops piled on, tasing Chuck three times before wrestling him into their car. The robbery was an international punchline: “Dive-by robber left high and dry,” wrote the Sydney Morning Herald.

This time around, Chuck’s PTSD would not help him escape the full brunt of sentencing. He was a repeat offender. Chuck took a plea deal for 16 years.

As with any prison sentence, the punishment would last far longer.

Donna Coma reviews documents she has accumulated dealing with Chuck’s incarceration, medical issues and military service.

Peter van Agtmael/Magnum Photos

Chuck frequently wrote Donna from prison, asking after her love life and his siblings; wishing her a happy birthday, Thanksgiving, 4th of July. When she planned to visit him at the penitentiary in Waymart, Pennsylvania, he included a page and a half of instructions. “Please buy you some mase (pepper spray) for your keychain especially coming alone,” he wrote.

That visit never happened. Chuck’s cellmate assaulted several corrections officers, and Chuck thinks the prison suspected he knew something about it. He and his former cellmate maintain he wasn’t involved in the attack. Before Donna could make it to Waymart, he was moved to the Special Management Unit at Lewisburg Penitentiary. (In court documents, the Bureau of Prisons claimed that Chuck met “multiple criteria” for being sent to Lewisburg, but did not specify which ones.) That’s when things get blurry.

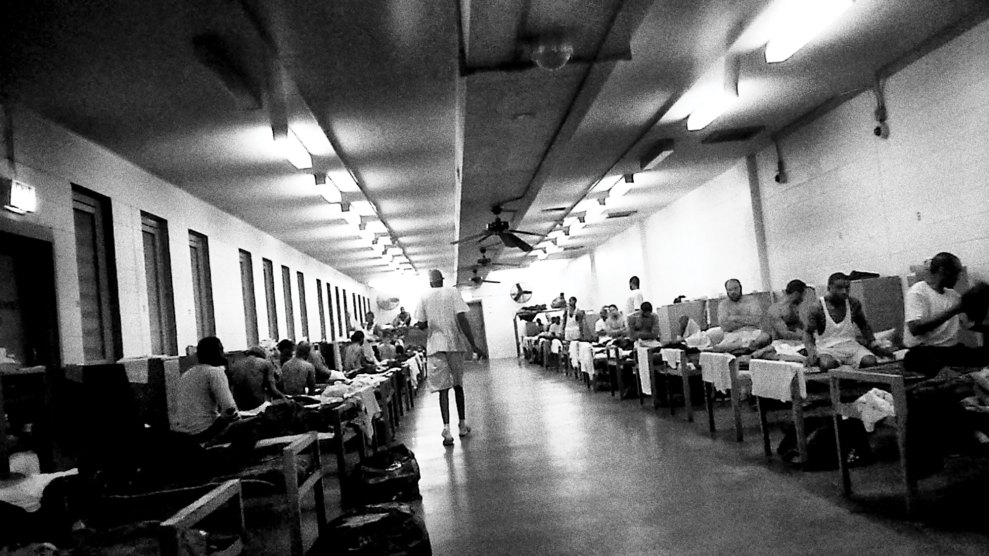

The SMU was meant to house the Bureau of Prisons’ most dangerous inmates, men who were deemed too volatile to live in the general population. But many say they landed there for lesser infractions. Regardless of why you were sent to Lewisburg, you spent nearly 24 hours a day—eating and sleeping and defecating—in an 8’ by 11’ concrete cell with another person.

Psychologists say the conditions could drive even the most stable prisoner to lash out, and that living in “double-celled solitary confinement,” a widespread practice in prisons across the country, can be even more mentally damaging than being locked down alone. A double cell at Lewisburg meant living under the constant, suffocating threat of violence. And when fights broke out, there was no escape.

Chuck doesn’t remember “the incident.” He recalls being housed with a cellmate who taught him to memorize the names of every US president. But he can’t remember his face. According to an internal investigation by the Bureau of Prisons, obtained by The Marshall Project and NPR through the Freedom of Information Act, Chuck’s “cellie” (whose name has been redacted in prison records) had killed a prisoner before. “As cellies go, I am very difficult and demanding to live with,” he told prison staff.

From the beginning with Chuck, the cellie told them, “it was pretty clear …that [we were] not going to be compatible.” Chuck talked constantly, boxed his mattress, and practiced karate kicks in the small gap next to their bunks, sending his slip-on shower shoes flying around the cell. The two asked to be separated, but they knew how Lewisburg worked. Without a serious fight, they wouldn’t be moved.

On February 26, 2016, recreation time was cancelled, erasing their only chance that day to escape their cell and each other. That afternoon, the chaplain discovered Chuck lying on the ground, one end of a bedsheet tied around his neck and the other to his cell door. His face was dark purple.

Officers yelled through the door at both men to cuff up. Chuck didn’t respond. They aimed their pepperball gun through the meal slot and fired, releasing pepper spray into the cell. Chuck didn’t respond. Finally, shields up, guards approached Chuck and slapped restraints around his wrists. Then they cut the makeshift noose from his neck.

When paramedics arrived, Chuck had no pulse. They tried CPR, applied the defibrillator to his chest, and rushed him to the hospital. It was in the ICU, as they lifted Chuck’s body off the stretcher, that a lieutenant first noticed it: Just above his tailbone was a clear, shoe-shaped bruise.

Chuck Coma at home.

Peter van Agtmael/Magnum Photos

When Donna first asked to talk to Chuck, prison officials told her he wasn’t able to speak around his breathing tube. It took nearly a month after the strangling to get Chuck on the phone. His voice was weak and raspy, and he was mumbling about his medication. “It was like he was talking to a stranger,” Donna said.

After Chuck stabilized, prison officials moved him to the main medical facility for the Bureau of Prisons in Butner, North Carolina. He was diagnosed with an anoxic brain injury, which occurs when brain cells die after being cut off from oxygen. When he arrived at Butner, he was confined to his bed, under 24-hour supervision, and fed through a tube.

Chuck’s sister Tracey created a Facebook group, “Rights for Federal Inmates and their Families,” to keep friends and family informed. The timeline logged their frantic efforts to get more information about Chuck’s condition, from writing to President Trump to speaking with a local newspaper reporter. They sent faxes to their senator and congressperson with the subject line: Help.

The group grew to more than 160 members, many of them strangers to the family but intimately familiar with the helplessness and anguish of having a loved one inside. They lived with the fear that what happened to Chuck could happen to their family members. Many knew what the Comas were learning—how prison can break a family, not just for the duration of a sentence, but because the person who leaves never really comes back.

Donna and Tracey still couldn’t get an incident report or any other record of what happened to Chuck. After their story appeared in the local paper, they were contacted by the Lewisburg Prison Project, a small nonprofit that investigates prison conditions and provides legal assistance. That’s how the family learned Chuck had been assaulted, thanks to information from other inmates. They were also connected with an attorney, Jennifer Tobin, to help them fight for more information and to bring Chuck home.

The family applied for compassionate release, a program that allows federal inmates to be released early if they are sick, elderly, or facing “extraordinary circumstances.” At the time, Chuck was barely walking, so Donna spent thousands of dollars to remodel her bathroom to make it wheelchair-accessible. But the Bureau of Prisons denied their application. Chuck, the prison officials claimed, was too volatile for Donna to control. It didn’t matter that in two years, when his sentence expired, Donna would be caring for Chuck regardless of his condition.

The Comas struggled for months to arrange a visit. Finally, in June 2016, Donna flew cross-country to North Carolina to see for herself how Chuck was doing. But when Donna and her son Rick arrived at Butner, officers would not let them in. They claimed she had failed to make a formal request, and that they didn’t have the staff on hand to monitor an impromptu visit. Soon after she returned to Shelton, Donna cried with frustration. “We were five minutes away from him,” she said.

In an email, Bureau of Prisons spokesperson Nancy Ayers declined to provide an interview or comment on the Coma family’s experience with the agency.

After a year-and-a-half of trying to arrange visits and get Chuck on the phone, Tracey posted: “We saw him!” When she and Donna arrived at Butner in July 2017, officers wheeled in a man they did not recognize. Chuck’s prison uniform sagged around his thin frame, and several of his front teeth were missing. He didn’t know where he was. His hands were too stiff to hold a soda can. He kept looking at a wristwatch that didn’t exist and trying to put on glasses that weren’t there. He recognized his mother and sister, although he remembered them as decades younger.

Donna left worried about what the future would bring. “He will never ever be Chucky,” she said soon after the visit. “It’s just like a bad dream that never ends.”

Chuck Coma at Joint Base Lewis-McChord.

Peter van Agtmael/Magnum Photos

Chuck Coma at home.

Peter van Agtmael/Magnum Photos

Chuck Coma looks at his Class A dress uniform and official service picture at home.

Peter van Agtmael/Magnum Photos

Chuck sat next to his sister Tracey on his mother’s brown leather couch one afternoon this April, his eyes wide. “You flew all the way out there, and they didn’t let you see me?” he asked. It was strange hearing the stories of the last three years—years he could not remember. The details of his life before the attack were slowly filling in, after his mother and Tracey reminded him. But the entire time he spent in Butner was missing from his memory.

“It’s crazy. I thought I was stronger than that. The last 10 or 15 years are all mixed up,” Chuck said. “Up until three weeks ago, I didn’t know if I graduated high school.”

Chuck now spent many of his days trying to push his body back to what it once was: kicking the punching bag in his front yard, running unsteadily around the neighborhood, teetering on a ladder to fix the shed he had built for his mom years ago. He dressed only in track pants and long-sleeve synthetic shirts, like he was ready for a workout at any moment.

But other days he could do little more than watch hours of Shark Tank, Alaskan Bush People, or CNBC, daydreaming of what life might have been like had things unspooled differently for him. “I think my body will heal itself,” Chuck said. “Soldiers don’t give up. Soldiers just keep fighting.”

Chuck had been sitting on the same couch one recent morning, staring out the window, when he thought he saw his dad drive by in his red truck. He started asking Donna: Did Dad know he was home? Why hadn’t he come to see him?

Tracey finally broke the news: Their dad, Gary, had died a decade ago. Chuck’s injury had just erased it from his mind. He sobbed as intensely as if it had happened that day.

Chuck Coma’s service picture on the wall of his bedroom.

Peter van Agtmael/Magnum Photos

Chuck and Donna Coma at home with Donna’s pet pig Rosebud.

Peter van Agtmael/Magnum Photos

Not long after Chuck’s homecoming in December 2018, he started getting confused and taking off. Donna would follow, slowly trailing him in her white Toyota as he shakily ran and fell off the side of the road. Donna sometimes called the cops for help. Once, when they approached him, he said there was a woman trying to kidnap him and refused to get in her car. Chuck ended up in the Shelton psychiatric hospital that day. Less than an hour after coming home, he took off again.

Chuck often exploded in frustration—a common side effect of traumatic brain injuries—swearing at Donna and threatening her. It was unlike anything she had witnessed before his injury. “No matter what kind of a fight we got into, he never talked to me like that before. Sometimes he acts like he’s still in prison,” Donna said, not long after a particularly bad outburst in August. “I knew it was going to be bad. But if I’d known it was going to be this hard, I think I’d have left him in there.”

His flashbacks continued to keep him up at night, the images of war blurring with what memories remained of his time in prison: getting sucker-punched by another prisoner and losing his front teeth, seeing guards body-slam other inmates, living in constant fear of someone coming at him with a homemade weapon.

When he thinks of “the incident,” Chuck partially blames himself. “I’m a soldier when it comes down to it. And what do they teach you being in the infantry? You never jeopardize your security. In prison, that should be even more in your mind than on the combat field,” he said. “I should have got out of that cell. I should have let them hurt me instead of going back. I made the worst mistake of my life.”

In some ways, Chuck knows he’s lucky. Some men never returned from Panama or from Lewisburg. The thousands who did carried that violence home with them.

Chuck Coma at home.

Peter van Agtmael/Magnum Photos

Last winter, the family filed a lawsuit against the Bureau of Prisons, claiming the agency fostered the violence that led to Chuck’s near-deadly assault by putting him into a cell with a known killer and ignoring requests to have Chuck moved. That attack, the Comas claim, was not an anomaly: It was one of the 3,076 inmate-on-inmate assaults in federal prisons that year. At Lewisburg alone, multiple inmates were attacked, killed, or mutilated by their cellmates, often after the attackers were denied their psychiatric medication or begged to be moved.

No criminal charges have been filed against Chuck’s former cellmate, according to the family’s attorney, and Donna says she was told the FBI investigation was closed. She feels relatively little anger toward the man who did this to her son, whose name she does not know. But she is furious at the system.

“It was the prison’s fault, they’re not paying attention,” Donna said. “You get put in there because you broke the law, but does that give them the right to maim you to the point that you don’t have a normal life?”

In their response to the lawsuit, attorneys for the Bureau of Prisons denied any allegations of negligence or failure to protect people in their custody.

Ayers, the bureau spokesperson, said in an email that the facility provides educational and therapeutic programming to decrease fights and to help every inmate “be a productive law-abiding citizen within their community in prison and ultimately their community beyond prison.” In addition, she wrote, “Staff are trained to notice signs of discord and to take action swiftly to prevent violence between cellmates and fellow prisoners.”

One sunny afternoon this fall, Chuck and Donna spent the day rushing from one appointment to another at the VA Medical Center in Tacoma, Washington. Donna often glanced over her shoulder to make sure Chuck wasn’t stumbling on the curb. His hands and feet were numb, his vision blurry.

“It’s a nice day,” Chuck said, staring at the sky. “I’d be skydiving if I had my other things in order.”

They started at the neurologist’s office. From his brain scan, his doctors knew that seizures weren’t causing his tremors, but they still didn’t know how to stop them. Then Donna drove to the VA dentist—Chuck was trying to get implants where his front teeth had been punched out. After that was the psychiatrist, to check his medications.

“I don’t even feel the meds, they don’t do nothing,” Chuck said.

“Yes they do,” Donna said. “Excuse me, what he’s got you on definitely levels you out.”

“I’ve got about that much patience with people,” Chuck said, pinching his fingers together.

“You used to be worse.”

Donna and Chuck’s doctors are impressed with his progress. His walking is steadier, his speech quicker, his mood brighter. On one of the last visits, he left swearing at his psychiatrist, telling him to watch his back. Today he’s agreeable. But he’s still frustrated by his neuropsychologist’s conclusion that he can’t manage his money or live on his own. He’s always trying to prove himself, noting whenever he navigates complicated hospital hallways or remembers the time of an appointment that Donna forgot.

“They’re keeping their thumb on me, they’re not letting me fly,” he said. “That ain’t right. I’m not incompetent.”

Donna shook her head; they’d had the same argument nearly every day since he returned. “I would love for him to get a different place, but I still think he’s vulnerable. He drives me crazy, but if he moved out, I would worry,” she said. “We fought, and we got him home, and now, nobody wants to help me with him but me.”