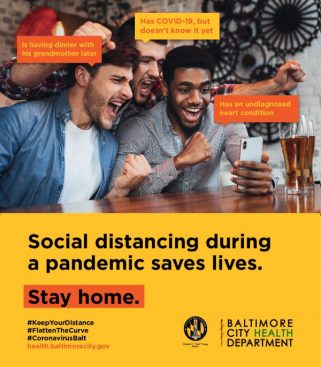

Jens B'ttner/AP Images

This story was published in partnership with ProPublica, a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up for The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox.

Five years ago, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services tried to plug a crucial hole in its preparations for a global pandemic, signing a $13.8 million contract with a Pennsylvania manufacturer to create a low-cost, portable, easy-to-use ventilator that could be stockpiled for emergencies.

This past September, with the design of the new Trilogy Evo Universal finally cleared by the Food and Drug Administration, HHS ordered 10,000 of the ventilators for the Strategic National Stockpile at a cost of $3,280 each.

But as the pandemic continues to spread across the globe, there is still not a single Trilogy Evo Universal in the stockpile.

Instead last summer, soon after the FDA’s approval, the Pennsylvania company that designed the device—a subsidiary of the Dutch appliance and technology giant Royal Philips N.V.—began selling two higher-priced commercial versions of the same ventilator around the world.

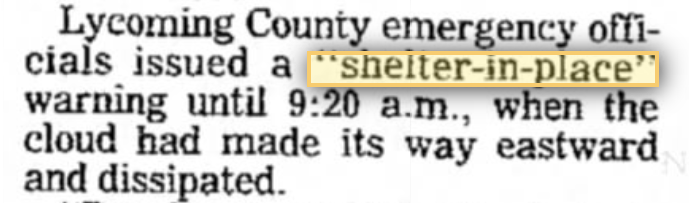

“We sell to whoever calls,” said a saleswoman at a small medical-supply company on Staten Island that bought 50 Trilogy Evo ventilators from Philips in early March and last week hiked its online price from $12,495 to $17,154. “We have hundreds of orders to fill. I think America didn’t take this seriously at first, and now everyone’s frantic.”

Last Friday, President Donald Trump invoked the Defense Production Act to compel General Motors to begin mass-producing another company’s ventilator under a federal contract. But neither Trump nor other senior officials made any mention of the Trilogy Evo Universal. Nor did HHS officials explain why they did not force Philips to accelerate delivery of these ventilators earlier this year, when it became clear that the virus was overwhelming medical facilities around the world.

An HHS spokeswoman told ProPublica that Philips had agreed to make the Trilogy Evo Universal ventilator “as soon as possible.” However, a Philips spokesman said the company has no plan to even begin production anytime this year.

Instead, Philips is negotiating with a White House team led by Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, to build 43,000 more complex and expensive hospital ventilators for Americans stricken by the virus.

Some experts said the nature of the current crisis—in which the federal government is scrambling to set up field hospitals in New York’s Central Park and the Jacob K. Javits Convention Center—underscores the urgent need for simpler, lower-cost ventilators. The story of the Trilogy Evo Universal, described here for the first time, also raises questions about the government’s reliance on public-private partnerships that public health officials have used to piece together important parts of their disaster safety net.

“That’s the problem of leaving any kind of disaster preparedness up to the market and market forces—it will never work,” said Dr. John Hick, an emergency medicine specialist in Minnesota who has advised HHS on pandemic preparedness since 2002. “The market is not going to give priority to a relatively no-frills but dependable ventilator that’s not expensive.”

The lack of ventilators has quickly become the most critical challenge to keeping alive many of the people most seriously sickened by the virus. Ventilators not only help people breathe but also can provide pressure that holds the lungs open so the air sacs don’t collapse.

Neither HHS nor Philips would provide a copy of their contract, citing proprietary technical information that would have to be redacted under a Freedom of Information Act request. But from public documents and interviews with current and former government officials, it appears that HHS has at times been remarkably deferential to Philips—and never more so than in the current pandemic.

From the start of its long effort to produce a low-cost, portable ventilator, the small HHS office in charge of the project, the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, or BARDA, knew that it might need to move quickly to increase production in an emergency and insisted that potential partners be able to ramp up quickly in the event of a pandemic.

But the contract HHS signed in September 2019 gave Philips almost a year before it had to produce a single Trilogy Evo Universal, and two more years to fulfill the order of 10,000 ventilators.

On the same day in July that the FDA cleared the stockpile version of the ventilator, it granted the application of Philips’ U.S. subsidiary, Respironics, to sell commercial versions of the Trilogy Evo. Philips quickly began shipping the commercial models overseas from its Murrysville, Pennsylvania, factory.

Steve Klink, the company’s Amsterdam-based spokesman, said Philips was within its rights under the HHS contract to prioritize the commercial versions of the Trilogy Evo. An HHS spokeswoman—who insisted she could not be identified by name, despite speaking for the agency—did not disagree.

“Keep in mind that companies are always free to develop other products based on technology developed in collaboration with the government,” she said in a statement to ProPublica. “This approach often reduces development costs and ensures the product the government needs is available for many years.”

Just last month, HHS gave a very different impression to Congress, hailing the Trilogy Evo it funded as a breakthrough in its campaign for pandemic preparedness.

“This game-changing device, considered a pipedream just a few years ago, is now available at affordable prices to improve stockpiling and deployment” in an emergency, the agency told Congress in a budget document delivered on Feb 10.

But less than two weeks later, officials overseeing the Strategic National Stockpile approached Philips with an urgent appeal: Start making our ventilators. On March 10, Philips agreed to a modification of the HHS contract—one that called for the company to produce the Trilogy Evo Universal “as soon as possible,” a spokesperson said.

However, in a subsequent statement, the HHS spokeswoman said Philips is only required to deliver the ventilators “as they are completed.” Klink, the company spokesman, said Philips was only committed to meeting the original contract deadline of 10,000 ventilators by September 2022.

Had government officials insisted that Philips first produce the ventilators that taxpayers paid to design, the government could conceivably be distributing all 10,000 to hospitals now. Last year, Philips plants in Pennsylvania and California produced 500 ventilators of various models per week; they sped up to 1,000 per week earlier this year, Klink said. At that pace, the stockpile ventilators could have been completed even if Philips devoted only part of its lines to their production.

Klink said the reason the company is not producing the stockpile ventilator is because it has not yet been mass-produced and would require time-consuming trial runs. In the current crisis, it’s faster and more efficient to continue producing the versions it is already making, he said.

Asked if Philips could hand over its Trilogy Evo Universal design to another manufacturer, he argued that the fundamental constraint on production is not the company’s assembly lines but its dependence on more than 100 smaller companies around the world that make the 650 parts needed for a hospital ventilator.

“We cannot sell a ventilator with only 649 parts,” he said. “It needs to be the whole 650.”

It is difficult to assess how much profit motives might be driving Philips’ decisions about which ventilators to produce because the company does not disclose how much it charges different clients for commercial models.

The commercial version of the Trilogy Evo has had its own problems. Not long after it began selling the ventilators last summer, Philips sent out recall notices to customers in Europe and the U.S., alerting them to a software glitch that prompted the devices to shut down without sounding their alarm. The software has since been updated and the problem solved, the company said.

Klink said Philips hopes to be making 4,000 ventilators of all types each week in the U.S. by October, and that it would prioritize “those communities and countries that need it the most.”

But as the pandemic spreads, desperate global demand for the commercial models of the Trilogy Evo is driving up prices sharply, and evidence from the chaotic open market for the devices raises questions about Philips’ stated commitment to prioritize the neediest.

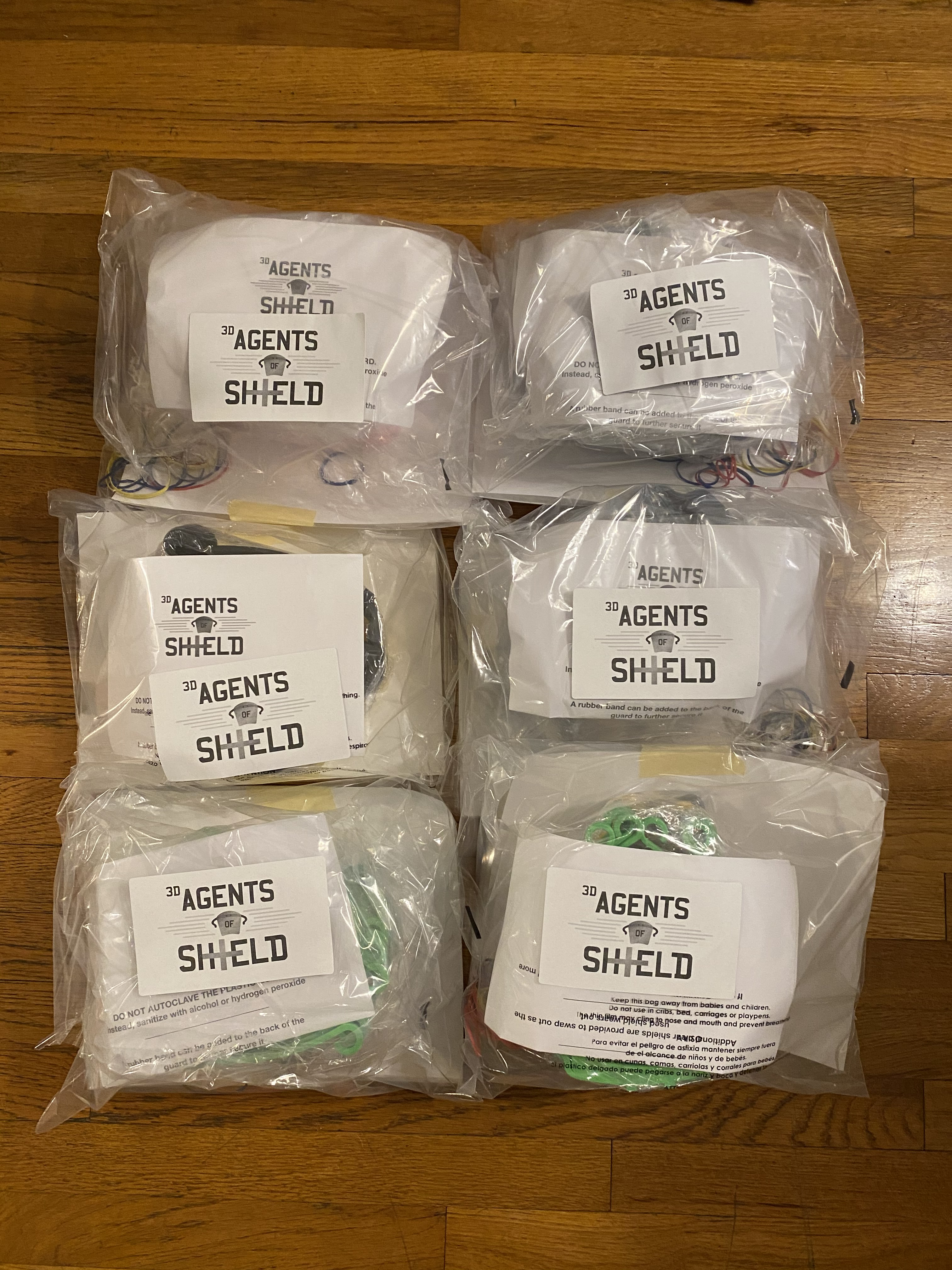

On Staten Island, a saleswoman at No Insurance Medical Supplies, who would give her name only as Jeanette, said the company was selling to “anyone who calls,” including doctors and individuals. The company’s first shipment of 50 devices sold out quickly, but an additional five ventilators arrived on Friday. The company requested 148 more, but Philips Respironics said it could only provide 11 ventilators by April 6, she said. The company’s prices are determined by what the manufacturer charges, she said.

The competition abroad is also intense. On March 12, the regional government of Madrid, one of the cities hardest hit by the virus, bought 10 Trilogy Evo ventilators from a Spanish medical supply company for about $11,000 each. In Budapest, Hungary, the Uzsoki Street Hospital announced that a local property development company had donated two “ultra-modern” Philips Trilogy Evo ventilators on March 18.

The struggle has grown so fierce that last week, a trade group representing ventilator manufacturers asked the head of the Federal Emergency Management Agency to decide for the manufacturers whom they should sell to first.

“We would appreciate the Administration’s leadership and the advice of clinical and other experts within the Administration in deciding how to allocate these products in the most effective way,” the Advanced Medical Technology Association wrote in a letter to FEMA Administrator Peter Gaynor.

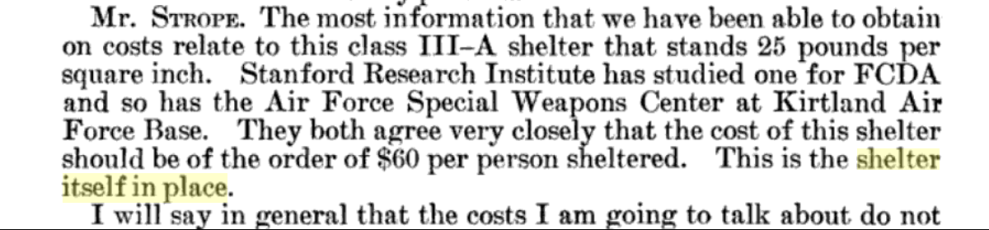

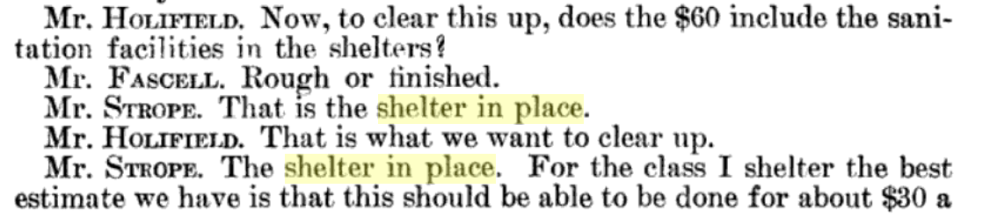

Medical experts and public health officials have believed for nearly two decades that they needed a less-expensive and simpler-to-operate portable ventilator that could be made and distributed quickly in an emergency.

“This is not a new problem,” said W. Craig Vanderwagen, a former senior HHS official who oversaw studies that led to the government’s early efforts to design and build a low-cost portable ventilator for such eventualities. “We knew back in the 2000s that ventilators were going to be critical in pandemic preparedness. That was a clear gap that we identified.”

In the early 2000s, American public health experts and government officials were gripped by a sense of urgency they had not felt before. The 9/11 attacks and the anthrax scare that followed underscored the need for sweeping new actions to keep the country safe. Outbreaks of Avian influenza—first reported in Hong Kong in 1997—exposed the public health system’s vulnerability to new, highly fatal pathogens from overseas. The George W. Bush administration’s disastrously slow and inept response to Hurricane Katrina in 2005 prompted widespread calls for the government to strengthen its ability to deal with a growing array of emergencies, from new, highly contagious diseases to previously unthinkable terrorist attacks.

One obvious vulnerability was to a viral pandemic or a chemical or biological attack that would ravage the lungs of its victims, setting off a cascade of cases of what doctors call Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome, or ARDS.

“None of us expected an event on the scale of what we’re going through now,” said Dr. Lewis Rubinson, a pulmonologist who participated in several of the early government-sponsored medical studies. “We had to guess: What would the patients look like? What we predicted correctly was that we could face massive cases of ARDS.”

By the early 2000s, officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had already begun working to stockpile a few thousand ventilators for such an eventuality, former officials said. But studies by medical experts and government scientists—including sophisticated models of what might occur in the event of various disasters, outbreaks or attacks—suggested a bigger problem. Hospitals could be crippled not only by shortages of complex and costly ventilators, but also by a lack of the trained respiratory technicians who are generally required to operate the machines.

The experts envisioned one important solution: a portable ventilator that was less complex than hospital machines and could be more quickly produced, safely stockpiled and widely distributed in emergencies. They envisioned a device that could be deployed in field hospitals like the ones that authorities are now rushing to create in Central Park and elsewhere.

The job of bringing such a device to life fell to BARDA, an innovative office of HHS that was established in 2006 to help the country prepare for pandemic influenza, new types of infectious diseases or an attack or accident involving chemical, biological or radiological weapons.

Much of BARDA’s work has been focused on developing potentially critical vaccines and other medicines that are not necessarily profitable for big pharmaceutical companies. The agency often works with medical researchers at the National Institutes of Health and elsewhere, identifying promising therapies and other innovations, and then forms partnerships with private biotechnology or other companies to create the drugs and move them through various stages of regulation.

In 2008, BARDA began trying to find a company that could make a ventilator that would be inexpensive—ideally, less than $2,000 each—and could be simple enough to use that “inexperienced health care providers with limited or no respiratory support training” could operate the devices during a pandemic, according to the agency’s solicitation for bids.

BARDA also anticipated the shortage of parts and competing priorities that the ventilator industry now faces. Companies bidding for the contract had to show they could secure the parts needed to “ramp up production to supply at least” 1,700 ventilators per month and 10,000 in six months’ time. The companies also had to pledge that government “contracts will be honored during a pandemic,” the initial solicitation said.

With only a couple of bids, BARDA settled on a small, privately held ventilator company in Costa Mesa, California, Newport Medical Instruments Inc. BARDA and Newport signed a $6.4 million contract in September 2010, specifying that the money would be doled out incrementally as the company met various milestones.

But in May 2012, Newport was purchased by a larger Irish medical device company, Covidien, for $108 million. Covidien quickly downsized and asked Rick Crawford, Newport’s former head of research and development and the lead designer of the BARDA ventilator, to finish up the project without any staff assigned to him. Crawford said he took a job with another company.

“I don’t know how you finish a project when nobody reports to you,” he recalled thinking.

A former BARDA official who worked on the project said that Covidien began raising issue after issue and demanded more money. BARDA agreed, eventually tacking on almost $2 million more to the price tag, records show. Even so, Covidien abandoned the project.

A spokesman for the still-larger firm that acquired Covidien in 2015, Medtronic, said that the prototype ventilator created by Newport Medical “would not have been able to meet the specifications required by the government, nor at the price required.” In a statement responding to a story in The New York Times, Medtronic said it left the federal government with all the designs and equipment created in the project.

Several former BARDA officials said such outcomes come with their territory. Like big pharmaceutical companies, they had to take chances, especially in the development of vaccines.

“There are going to be risks like that when you partner with businesses,” said one former senior BARDA official, who, like others, asked for anonymity because she was not authorized to speak for the agency. “It’s a problem that we at BARDA had encountered before, where a company changed hands and changed priorities.”

In March 2016, less than two years after signing its ventilator contract with BARDA, Philips Respironics agreed to pay $34.8 million to settle a Justice Department lawsuit under the False Claims Act and the Anti-Kickback Statute. Justice lawyers accused the manufacturer of effectively paying kickbacks to medical suppliers to buy its masks for sleep apnea. The company also agreed to abide by a five-year Corporate Integrity Agreement with HHS inspector general that imposed a series of oversight measures on the company’s operations.

With BARDA’s continuing support, Philips finally won FDA approval for the Trilogy Evo Universal ventilator in July 2019. Klink, the Philips spokesman, said the $13.8 million from HHS covered only a portion of the design and development costs for the ventilator and that the company invested more.

Rubinson, now the chief medical officer of Morristown Medical Center in Morristown, New Jersey, praised the BARDA effort as essential, adding that if 10,000 ventilators seems like a small number in the COVID-19 crisis, it had to be understood in the context of government officials’ typical unwillingness to buy equipment it might only need in an emergency.

“They could have bought a million ventilators,” he said. “And then you would be writing about the boondoggle of all these devices that never got used.”

Today, the government’s failure to obtain the Trilogy Evo Universal is seen by some experts as the real game changer.

“Even if a few months ago we had taken dramatic action to develop these kinds of ventilators, it would have been better,” said Hick, the emergency medicine specialist in Minnesota. “If I had a ventilator that cost $4,000 rather than $16,000, I’d be in better shape. We can buy a lot more of them.”

Claire Perlman contributed reporting.