Roman Pimenov/TASS/Zuma

Perhaps you’ve seen this recent viral video: In an hourlong Zoom video call posted to Vimeo, Cornell Weill Medical Center pulmonologist Dr. David Price assures viewers that the coronavirus isn’t nearly as contagious as we’ve been led to believe. The video, which has amassed nearly 5 million views and was touted by Fox News commentator Jesse Watters, includes one particularly empowering tip: You can’t get the coronavirus unless you’ve had sustained, close contact with someone who has been infected.

While the advice may comfort viewers at a time of uncertainty, the truth is more complicated. We broke down the science behind some of the assertions in the video.

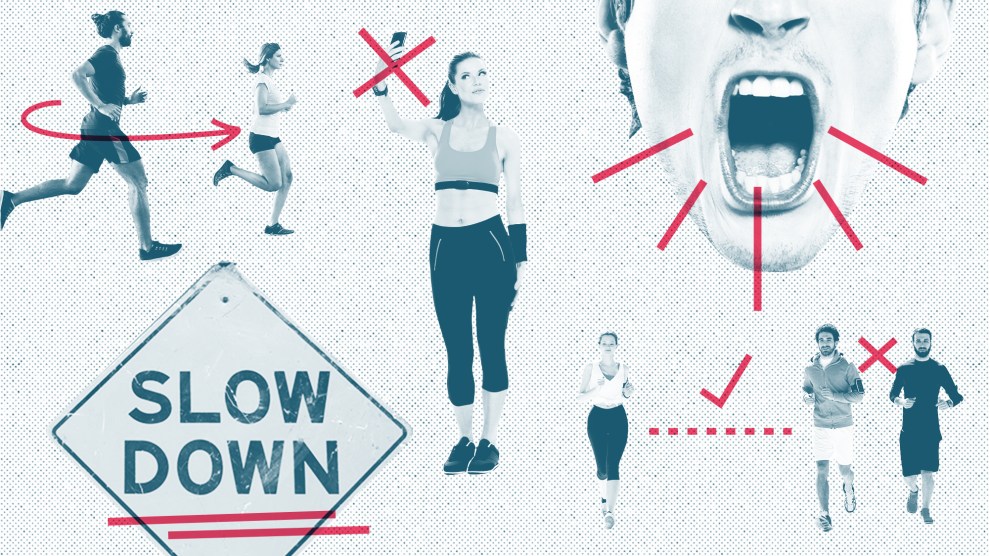

“The thought at this point is that you actually have to have very long, sustained contact with someone—and I’m talking about over 15 to 30 minutes in an unprotected environment, meaning you’re in very closed room without any type of mask—for you to get it that way.”

Not exactly. Dr. Jill Weatherhead, an assistant director of infectious disease at Baylor College of Medicine, explained that sustained contact with an infected person may indeed increase a person’s likelihood of contracting the virus. “That’s why we talk about physical distancing, because the closer you are in contact with somebody in terms of your physical distance—and for a longer period of time, where you’ll be exposed to more of those particles—the more likely you will contract the virus.” But the idea of setting a time limit of 15 or 30 minutes isn’t based on science. It’s entirely possible for someone to become infected within a much shorter timeframe.

“The overwhelming majority of people are getting this by physically touching someone who has this disease or will develop it in the next one to two days and then touching their face.”

Actually, we’re not sure how exactly the majority of people are contracting coronavirus—that would be almost impossible to prove. “Those risks are really difficult to quantify,” said Dr. Angela Rasmussen, a virologist and associate research scientist at Columbia University’s Center for Infection and Immunity. “The droplet transmission depends on so many different variables.”

“We know that if you keep your hands clean, that you’re not gonna get this.”

Dr. Joshua Petrie, a research assistant professor in the Department of Epidemiology at the University of Michigan’s School of Public Health, points out this claim is “somewhat in contradiction to the earlier [point] that you have to have direct contact with people.” He adds, “Hand washing is also important, but social distancing is definitely the most important thing to be doing.”

What’s more, it’s impossible to know exactly how effective hand-washing is in curbing the spread of the disease without knowing how commonly people get sick from touching contaminated surfaces—though they likely pose less of a threat than infected people.

“What are the chances that you are going to touch exactly that site that has the most virus on it and then touch your nose, and how much of that virus was transferred from that surface, to your hand, to your nose?” Rasmussen said. “These things are really difficult to put numbers to, but that’s why the risk of fomite (surface) transmission is probably much lower than for respiratory droplets.”

“When you know that the only way you’re gonna get this disease is if your hands are dirty, and that if you touch your face, and that if you are way too close to that person, that becomes incredibly liberating. All of a sudden, the person at the store is not your enemy. They’re someone who’s going through this with you.”

It’s a little more complicated than that. Petrie describes essential activities like going to the grocery store or pharmacy, when done cautiously and infrequently, as “relatively low risk.” That’s largely because the virus is not thought to spread through aerosols—infectious particles smaller than droplets that can linger in the air. Instead, is spreads through heavier viral droplets that quickly fall to the ground. But it’s unclear how far those infectious droplets can spread.

“Any time that you’re going to be in crowds and public spaces, there’s always going to be a risk of viral transmission between people,” Weatherhead says. “When you’re doing those activities, you still need to have stringent protocols that you’re following. When you go in, you’re washing your hands. You’re trying to keep distance between people while you’re there.”

Of course, your risk depends on how long you spend at the store, and how many people you interact with there. Since the video was made, several grocery store workers across the country have died of COVID-19 and many more have been infected, the Washington Post reports.

Cornell Weill Medical School did not respond to Mother Jones‘ request for comment on the assertions in the video.

“I just caution people to think about what we do know, but also keep an open mind that we may have to change our views on how we’re managing every every aspect of this crisis, based on the evidence as it comes in,” says Rasmussen. “The real take home message of all this is there’s a lot more that we don’t know than what we know.”