Erica Harris and her daughter Jordan wear their protective masks as they walk home on Chicago’s South Side.Charles Rex Arbogast/AP

A few weeks ago, a thought woke Camara Jones up in the middle of the night. It was about the coronavirus. That’s commonplace these days, but Jones is a family physician and epidemiologist who worked at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, where among other things she studied racial bias in the medical system. Her thoughts on a pandemic are anything but commonplace.

The coronavirus had revealed something essential about the workings of race in America. “The thought that woke me up,” she told me over the weekend, “is that the most profound aspects of racism operate without bias and without stigma.” What she means is that racism in its most pernicious form slides by on deniability, without any of the telltale oafishness with which more ordinary forms of prejudice announce themselves. Left in its wake are lopsided outcomes that are made to look like the natural order of things.

Nothing illustrates that dynamic better than a pandemic that is wrongly said to be “the great equalizer.”

“This disease,” she says, “is not an equal-opportunity disease.” Black people are contracting the coronavirus and dying from the disease at higher rates than other people. This disproportionate effect is a social issue in the guise of an epidemiological one. Black Americans, particularly in the Southern states that have not expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act, are more likely to be uninsured. They’re more likely to work a low-paying job. They’re more likely to suffer from heart disease, asthma, cancer, and other conditions, not—as Jones takes pains to emphasize—because of biology. It’s because of straightforward social choices such as where toxic dumps get sited, where new highways get built, and where Black people have historically been permitted to live.

It will be hard to fully grasp the scale of disparities in coronavirus outcomes. Cities and states thus far have been slow to collect data by race and ethnicity. From what we know now, though, the pattern is troubling. In Chicago, for instance, 69 percent of people who have died from the coronavirus as of April 8 are Black, even though they make up 32 percent of the city’s population. In Michigan, where an outbreak has gripped Detroit and where Black people make up 14 percent of the population, they represent 40 percent of deaths. In Louisiana, where an outbreak has rattled the New Orleans area, 70 percent of those who have died are Black. In Alabama, Black people make up 27 percent of the state’s population but 52 percent of those who have died from coronavirus. In Mississippi, where Black people make up 38 percent of the population, they make up 56 percent of coronavirus infections and 72 percent of deaths. And as ProPublica reported, Black residents in Milwaukee County, who make up 26 percent of the county’s population, constitute half of its COVID cases and 81 percent of its deaths.

In New York City, Black residents make up 22 percent of the population and 28 percent of deaths. In Los Angeles, though early data is limited, Los Angeles County public health director Barbara Ferrer reports that Black people “have a slightly higher rate of death than other races.”

Jones sees the effects of racism everywhere in the coronavirus outbreak. She points to the way the disease has ravaged jails and prisons, which are disproportionately Black because of disproportionate policing. In Chicago, for instance, 238 inmates and counting at Cook County Jail have contracted the disease. In Louisiana, five people have died of coronavirus as 42 inmates and staffers have contracted the disease. At the jail complex in New York’s Rikers Island, more than 160 inmates have contracted the disease, including one who died while serving a parole violation.

I spoke to Jones over the weekend about how the coronavirus has pulled the cover off the preexisting condition of American racism. The transcript below has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

What has stood out to you so far as we’ve watched the coronavirus pandemic unfold?

What the COVID-19 pandemic is unveiling is the structural racism, which is why we see people of color and poor people more profoundly impacted. This virus is an equal-opportunity virus, but this disease is not an equal-opportunity disease, and it’s manifesting itself more severely in people of color who’ve been historically oppressed and disinvested.

So the way that you need to talk about racism in this time is to explain, to make it clear to everybody looking at this, that it’s not some kind of inherent weakness of African Americans that’s making them die more frequently of the disease than other people in Milwaukee, in Detroit. That is an impact of racism, so what we need to do is un-invisiblize structural racism and say this structural racism and the historical federal partitioning of our cities into racially segregated neighborhoods, the disproportionate placement of toxic dump sites, that stuff which is giving us more asthma, more lung disease, or the HIV epidemic—these are the old aspects of racism showing up during this pandemic.

We have already seen some of those in terms of the stigmatization of Asian people. But as anti-racist activists, this is the time for us to say that what has previously been invisible to many is now manifest. It’s not a result of poor people being weaker than, having bad habits, being stupid or lazy or anything. This is racism showing up. We need to name what we are starting to show in our statistics. We need to label the racism that it is.

How do you public health officials go about doing that?

By talking about the racial/ethnic health disparities that many people in this country aren’t even aware of. Many are not aware that Black people are more likely to have heart disease and kidney disease and be obese and have diabetes. So to talk about the so-called preexisting conditions that are putting people at higher risk—that these things are because of the conditions of our lives. It just so happens that people of color have more of these diseases, and that they are having worse outcomes, but there’s nothing biological about race. Race is the social interpretation of how we look in a race-conscious society, and racism is the system that operates on that so-called race to structure opportunity and to assign value.

To what extent have you seen public health officials address this racism?

I know that Barbara Ferrer, when she was here in Boston, we worked together a lot and she was very much anti-racist. When she was the head of the Boston Public Health Commission, every single employee went through anti-racism training. Every single training was half people from the health department and half community people. It took a long time, but her commitment to having people understand racism as a root cause of racial health disparities was clear. So I don’t know what she’s doing. I don’t know [if] she’s naming racism yet or she’s being very clear about collecting and showing data by race/ethnicity. That would be one way that a health director would do it. It doesn’t just happen that Milwaukee had the statistics and reported the statistics. Two years ago, Milwaukee County declared racism to be a public health crisis. The health department did that because the Wisconsin Public Health Association did that, and the Wisconsin Public Health Association did that because, when I was president of the American Public Health Association, I launched our association on a national campaign against racism and I went around to 25 of our 54 state affiliates talking about that. The Wisconsin Public Health Association said that racism was a public health crisis and then Milwaukee County took that.

That is why Milwaukee was the first one to put these data up. A health department person who has never said the word racism, they are not in this crisis all of a sudden going to jump all the way to understanding that racism is at the root of disparate outcomes, disparate testing, disparate hospitalizations, disparate access to ventilators. They may not have that. But the people who understand how racism works and that racism is a root cause, a fundamental cause of our so-called racial health disparities, now understand that the health disparities are really disadvantaging people in two ways. It’s making them get the disease worse, and then at the point where there’s gonna be rationing decisions made, God forbid, those same comorbidities, preexisting conditions might disqualify those people who have greater need from getting access to the life-saving therapies that they need. That was certainly the case in Italy, where I believe that they were using age and comorbidities as rationing criteria.

So I’m understanding what you’re saying here: There’s a fear there that because of these preexisting conditions, folks who disproportionately have those conditions, which are people of color and poor folks, that that could play into the ultimate decision-making of who lives and who dies.

Right. It’s playing in two ways. It’s making people sicker. You know, some people get the virus and don’t even experience symptoms, and some people get the virus and they get very sick. And people who have preexisting conditions are more likely to get very sick. So now they go to the hospital. The fear is, and in Italy, the reality was, that the very fact that they have diabetes or they have chronic lung disease or hypertension or some other kind of heart issue, that those things are going to be counted against them if a decision has to be made of which of these patients get the last ventilator.

So it’s a double whammy that we cannot let be. If you were to disqualify people or even ding them a little bit in terms of a priority- based on preexisting conditions, that will systematically disadvantage people of color in this country. That will be the ultimate expression of racism in the distant, hands-off kind of way. So it’s not about the stigma. It’s going to perhaps be about the criteria. We’re applying these criteria evenly to everybody, but without recognizing that the historical injustices that have made themselves evident in people’s health status is not evenly distributed.

The most important ways that racism is showing, has always shown up, and will continue to show up in this pandemic is not about stigma or name-calling or any of that. It’s about life-and-death decisions. It’s about historical disadvantages that we as a nation haven’t even recognized because we’re ahistorical. We act as if people have equal opportunity. We act as if the present, we’re disconnected from the past. I have seven different barriers like that, that I have distilled as barriers to achieving health equity. All of these are manifesting big time in this pandemic, and they don’t require interpersonal expressions of bias or discrimination. They’re baked into the system.

[Jones later emailed me her seven “societal” or “cultural” barriers to achieving health equity. They are: a “narrow focus on the individual,” an “ahistorical stance,” the “myth of meritocracy,” the “myth of a zero-sum game,” a “limited future orientation,” the “myth of American exceptionalism,” and “white supremacist ideology.”]

So scapegoating would manifest itself in devaluing somebody’s life when you have to make a life-or-death decision about them: When you have to decide as an EMT whether or not you are going to put this person in your ambulance and take them to the hospital, when you have to decide in the emergency department if you’re even going to intubate that patient and send them up to the ICU or not. So the scapegoating and the stigma also are going to be manifest through individual decisionmaking, where how an individual values the other person is going to play a part. But what I keep getting back to is that that’s going to play a much smaller part than all of the structural racism that is written into our bodies.

How are you seeing that structural racism play out as you think about the early data. You pointed to the ProPublica story. Are there particular places or ways that you’re seeing this structural racism play out?

Yeah, in the jails and prisons. Many people are held in jails because they can’t make bond and so then there’s a big push right now for decarceration But also in the prisons, where people of color are hugely overrepresented and the prisons are crowded. That’s another manifestation of structural racism categorically putting some populations at higher risks than others.

It’s not even the preexisting conditions anymore. It’s the housing or lack thereof. It’s the detention and detention centers and the like, and the disregard. That has to do with the values piece. It’s not a new values piece. It’s as if people do not recognize the genius that is locked away in our prisons and in our detention centers, so we don’t value those people and we’re just locking them away as if they could do very well without those people. Now we’re acting as if there’s a big epidemic inside a prison, oh well. That is a values piece that is becoming more vivid when we know that just one guard needs to come in there with COVID-19 asymptomatic and everybody’s going to be harmed. Then when you think about housing—again the structural racism is not just how it has made us have more preexisting conditions; it’s also where we find ourselves. Do we find ourselves unhoused? Do we find ourselves incarcerated? Do we find ourselves crowded in living quarters? Do we find ourselves with very tenuous jobs? Do we find ourselves with the jobs of home health aides continuing to take care of elderly people and the like, and needing those jobs? Do we find ourselves with the low-paid health worker jobs in the hospitals? Do we find ourselves cleaning up the rooms and the ICUs? Do we find ourselves taking the recently deceased bodies to the refrigerator truck? So it’s not just about what happens in individual bodies, but also where do we find our bodies?

What have you noticed in this pandemic, given the messaging from Washington? What have you noticed in terms of whether federal health officials are paying mind to all sorts of communities?

It’s rough. I don’t know what’s going on over there at the CDC. It is mind-boggling. [Laughs.] I mean, this is what we’re supposed to be leading. I mean, Tony Fauci is fabulous. He’s NIH, infectious diseases. But the whole approach to this pandemic in the US has been a very clinical approach narrowly focused on the individual and not at all the kind of public health population-based approach that we need, especially when it comes to testing. Maybe it was two weeks ago—I think it was two Sundays ago—I was listening to one of the shows, you know, the show that comes on every afternoon. You know what I’m talking about? [Laughs.]

I know exactly which one.

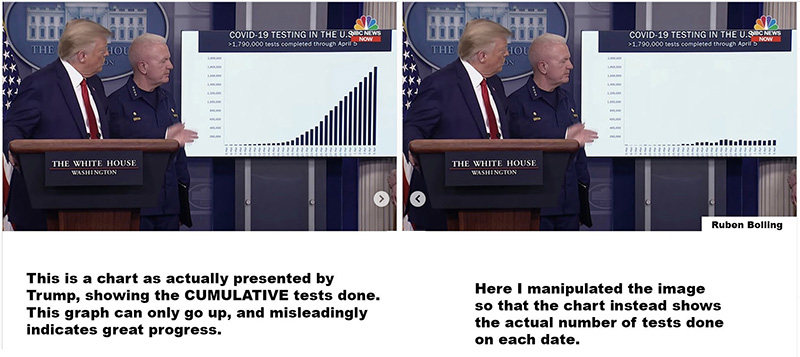

And I believe that the president said something like, they were about to announce that they were going to restrict testing to only those who are already hospitalized and maybe frontline people. They loosened that up again, but at that time they were saying that unless you were sick enough to already be hospitalized, you would not be able to get a test.

That is exactly the wrong approach. What that does is set a narrow, individually focused clinical approach where what you’re trying to confirm is a diagnosis that you already highly suspect. And confirming a diagnosis is good because if somebody doesn’t have COVID-19, if they have bacterial pneumonia, you want to treat them for bacterial pneumonia, and if they don’t have COVID, you don’t have to waste your precious personal protective equipment when you go into that person’s room. That’s important. But that is only going to be documenting the course of the epidemic. It’s never going to equip us to change the course of the epidemic, and a public health approach to testing is all about surveillance.

Which means that, sure, you can test all of the people who are symptomatic, but you also have to test at least a sample of people who are not symptomatic. You need to do that to know how widespread is the infection in our community today, which will equip you to plan what health resources you’re going to need in two weeks. Then it also helps you identify previously unknown infected people and to have them isolate themselves and then to also ask them, who did you get in contact with in the past six, seven days? And then you do that contact testing, you get other people early on in their infections, and then you isolate them. This is how you change the course of the epidemic as opposed to just documenting the epidemic.

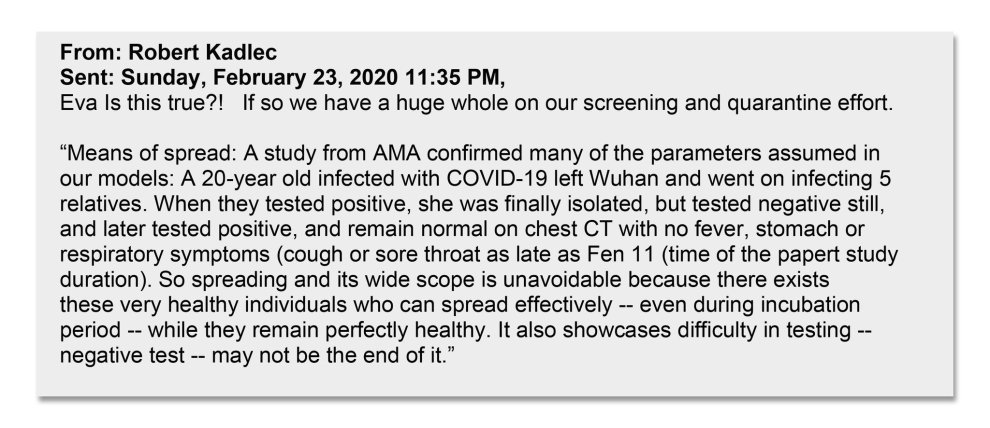

The CDC is the nation’s lead public health agency. There are many brilliant people at CDC who know that what I’m saying is absolutely the truth, and they are not satisfied, I’m sure, with just the clinical use of the testing to document the course of the pandemic. They want to influence the course of the pandemic, but we cannot do that without a public health surveillance approach to testing. Why CDC is not making a bigger noise about that, I have no idea. Who put the muzzle on whom? Because there are smart people there. They know this. This is not some aha.

What’s the impact when you have a president who calls the virus a “Chinese virus” and starts to label the virus based on geographic reasoning?

It’s horrible. It has a very bad effect. It makes [Asian Americans] scared, and it makes them understand that they are purposely being made vulnerable, that they are purposely being scapegoated in the same way that he scapegoats Muslims, in the same way that he scapegoats Mexicans. It’s another othering. It’s another part of his effort to make America white again.

How does the labeling affect the work of public health officials who have to go out there and combat the epidemic?

I haven’t heard anybody saying it is not the Chinese virus or President Trump is wrong to call it the Chinese virus. I think that they just themselves do not call it that, but perhaps the stronger response would be to defy the president in that labeling.

How does this labeling create fear among those who are labeled?

On the ground, public health folks know that before December of 2019 there was no person on this Earth who was immune to this virus. So public health people understand that we are all vulnerable. I don’t think public health workers are confused about that—all of humanity is at risk, and it’s not because of any particular part of humanity. It’s because of bats and pangolins. [Laughs.]

Right.

So public health people on the ground and public health leadership are so far away from the president’s frame that maybe they should get a little bit closer to actively defy that frame. But he’s stopped doing that now. But I would have to say that public health people who stood up to the president and actively defied him might find that their public health departments or their states were punished. So maybe not defying the labeling is a strategic thing because people know that they need tests and that they need ventilators and PPE.

What does an anti-racist initiative look like? How does the strategy around combating that sentiment evolve as the disease evolves, as what we know about the disease evolves?

Now it’s not the “Chinese virus.” Now it’s New Yorkers going down to Florida. So the xenophobia has shifted. Now it’s about, “Don’t let those New Yorkers come into your state,” and the whole 24-hour threat of quarantine, of an active military imposition of a quarantine on New York. So it’s about blaming and it’s about othering because the president and his supporters do not want to have any blame come back to them. So I would say that the president is racist. He has used many racist tropes before, and so when he would call it the Chinese virus, those were racist tropes again. But as it becomes clear that it can affect anybody, he has moved to the urban trope. You know, “Okay, New Orleans and Detroit and New York, you don’t want those people coming near you, but yes, we can let things open in the Midwest because those kinds of people aren’t here and so the virus will never come here” type of thing. It’s going to put his supporters at a severe disadvantage because if they’re still thinking this is some kind of hoax, this doesn’t mean they should go to as many parties as they want or barbecues or church next Sunday—they’re gonna get very sick.

But he’s always deflecting blame. He’s loosened up the Chinese part of it. Now that there’s going to be data out there about how people of color are overrepresented in terms of stats and all that, who knows, he might start blaming Black folks and Latinx folks. “You don’t want them to come into your neighborhood.” That’s all because he cannot understand that his sluggishness, his lack of future orientation, his narcissism, all of that has made him not act in a time of need. He still isn’t fully acting in a time of need but he will never blame himself. The thing he’s going to say, I already hear it—the low projections of 1.2 to 2.2 million Americans dying, right? Say that is not the 100,000 to 150,000, say it’s 500,000. He is still going to say, “Oh, because of our actions, we prevented the 2.2 million.” So he’s gonna always play this as a win even though his sluggishness and inaction in the face of need has caused already too many Americans to die. These people did not have to die.

So in Chicago, 70 percent of the people who have died from COVID are Black. What do you make of that?

Two things: that we started out sicker, probably in more crowded conditions and not able to work at home. Still have to be Uber driving. Still have to be delivering food to other people. Still have to be at the grocery store. Still have to be the home health aides and the nurses and doctors. I haven’t seen these data, but perhaps because of the profound residential segregation by race, which then segregates health resources and the like, they may find themselves in hospitals that don’t have enough of what’s needed. So it’s the three things: worse baseline health, the conditions of our lives and our work, and our access to sufficient health care.

How does that fit into what we’re seeing in other cities?

This is the distinction that needs to be made. The coronavirus does not discriminate in terms of whom it infects. But the disease discriminates in how profoundly those people are affected. All this did was pull the covers off.