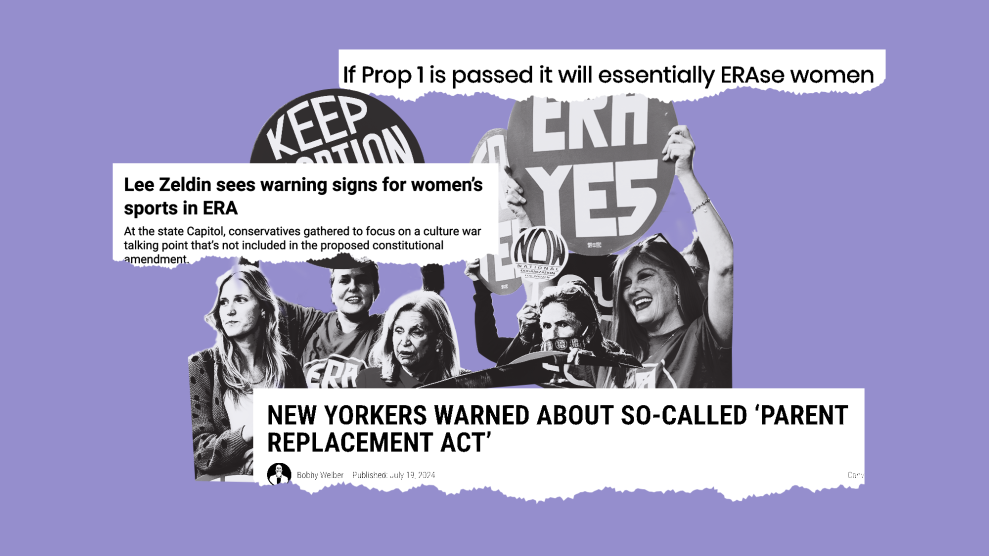

Mother Jones illustration; Jose Luis Magana/AP

In late August, on the fringes of a press conference outside New York City Hall, a man wearing a “Kill your local pedophile” T-shirt and a “Babies Lives Matter” pin screamed at a transgender woman who had shown up to protest the speeches. “Is it a boy or a girl?” the man yelled at the protester, gripping a rainbow Trump flag in his fists. “She shaves her armpits, so it must be a man,” he spat, cursing and hurling epithets.

On the podium, the transphobic messaging was less vile but no less overt. Speakers were urging the small crowd to vote against Proposal 1, a measure on the November ballot that would strengthen protections for abortion in New York state—and much more. Prop. 1 is a statewide version of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), the 101-year-old feminist effort to guarantee equal rights for women in the US Constitution. While the federal ERA has been largely stalled since the 1970s, many states have adopted their own versions. New York’s constitution, however, currently bans discrimination based only on race and religion, not sex. That could change if voters accept Prop. 1’s expansive vision of equality, which includes protections for segments of the population that historically have been marginalized and demonized, including LGBTQ people.

In a year in which support for abortion rights could determine control of statehouses, Congress, and the presidency, Prop. 1 seemed like a shoo-in, especially in the blue state of New York. Yet with a little over a month before the election, the effort to pass the New York ERA has been stumbling. An opposition campaign, calling itself the Coalition to Protect Kids, has fixated on the amendment’s protections for trans people, exaggerating its impact on women’s sports and pushing misleading claims about its effects on parental rights. “By solidifying new constitutional rights based on gender identity, Prop. 1 is sacrificing the rights of girls,” Amaya Perez, the New York chapter leader of Gays Against Groomers, a right-wing group known for pushing extremist anti-LBGTQ narratives, said at the press conference.

Those tactics appear to be working. Leaked polling from the pro-Prop. 1 campaign shows that voters find the opposition’s messages extremely persuasive. Months ago, Democrats saw the amendment as a means of motivating liberal turnout in November. Now, state Democratic politics are in a precarious state following the indictment of New York Mayor Eric Adams, and Republican candidates are turning the tables, using opposition to Prop. 1 as a rallying cry for their own voters.

“They’re trying to use [trans rights] as a wedge issue,” says Faris Ilyas, policy counsel at the New Pride Agenda, an LGBTQ rights group supporting Prop. 1. “Even in New York, it’s a working strategy. We’re a little bit scared of what might happen in November.”

It’s an old trick in conservative politics to argue that equal rights are bad for women. The federal ERA, which says equal rights cannot be denied “on account of sex,” was first drafted by leaders of the women’s suffrage movement in 1923 and introduced in every session of Congress for the next five decades. After it finally passed both the House and Senate in 1972, the next step was to go to the states: An amendment must be ratified by three-quarters of state legislatures before it can be added to the US Constitution. But conservative lawyer Phyllis Schlafly mounted a successful guerrilla campaign claiming the amendment would erase all differences between men and women in the law, thus forcing women into military combat, permitting same-sex marriage, and allowing men to use women’s restrooms. The ERA failed to reach the ratification threshold within the seven-year deadline, though efforts to revive and certify it continue.

Even without the ERA, Schlafly’s predictions have more or less come true: The culture already was shifting toward the kinds of gender equality the amendment attempted to codify. Yet her arguments still hold power. Warnings about mixed-gender bathrooms were used to defeat Houston’s Equal Rights Ordinance in 2015—around the same time conservative legal and political organizations, including the Schlafly-founded Eagle Forum, began whipping up the contemporary anti-trans panic, starting with bills restricting trans students’ bathroom access.

The version of the ERA that will appear on New York ballots doesn’t include the word “abortion,” but it was designed first and foremost to protect the right to choose. The effort started in 2019, when Democrats took control of the state Senate for the first time in a decade. They swiftly passed the Reproductive Health Act, removing abortion from New York’s criminal code—where it had been largely forgotten during the Roe v. Wade era—and protecting access to the procedure through 24 weeks’ gestation. (The new law also allowed abortion later in pregnancy if the fetus was not viable or if the pregnant person’s life or health was in danger.) But soon after, state Sen. Liz Krueger of Manhattan, who had spent a decade shepherding the new law, decided the work wasn’t done. “I realized, nope, not good enough,” Krueger says. “We’ve got to actually start to open up our constitution and modernize it.”

With the confirmation of Justice Brett Kavanaugh to the US Supreme Court in 2018, anti-abortion strategists finally had the far-right majority they needed to overturn Roe. “We were basically a pro-choice blue state with people not really understanding how at risk we were from bad law,” Krueger says. If New York enshrined abortion rights in the state constitution, she figured, those protections would be harder to repeal if the political winds eventually shifted.

So Krueger and Assembly Member Rebecca Seawright, also from Manhattan, convened scholars and reproductive law experts to craft an amendment. Rather than simply writing protections for abortion seekers into the constitution, they decided to swing for the fences: a measure modeled on the federal ERA but even broader. In addition to existing protections for race, color, and religion, Prop. 1 would ban government discrimination based on disability, age, ethnicity, national origin, and sex—including sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender expression. The resulting amendment, now known as Prop. 1, would make New York’s anti-discrimination protections the “most extensive” in the nation, says Ting Ting Cheng, director of the ERA Project at Columbia Law School, who consulted with the drafters.

“We were basically a pro-choice blue state with people not really understanding how at risk we were from bad law.”

There are nine other abortion rights ballot initiatives across the country this year, but when it comes to reproductive rights, New York’s ERA is unique. While most of the other measures essentially restore Roe, New York’s approaches abortion “as a matter of gender equality,” says Katharine Bodde, policy co-director of the New York Civil Liberties Union, one of the amendment’s chief backers. To accomplish this, it explicitly says discrimination based on pregnancy status, pregnancy outcomes, and reproductive health care and autonomy count as “sex discrimination” and are forbidden. The idea is to leave little room for judges to interpret the ERA in ways that wouldn’t protect abortion rights or pregnant people in the future. After all, courts have wide latitude to interpret ambiguous language, and they sometimes reconsider their old interpretations—as the US Supreme Court did when it reversed Roe. This past spring, Florida’s Supreme Court overturned a prior decision that said the state constitution protected abortion—after being stacked with judges appointed by Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis. And the Iowa Supreme Court has upheld a six-week abortion ban despite the state’s ERA, which broadly enshrines gender equality but doesn’t get into specifics. “We’re taking no chances in New York with courts interpreting ‘sex discrimination’ narrowly,” Bodde says.

That scares abortion opponents. New York’s Catholic bishops told their 35,000 mailing list subscribers in September that Prop. 1 would “permanently legalize abortion without restriction” and “render impossible any change to the law if the hearts and minds of New Yorkers were ever to shift toward protecting the child in the womb.”

Prop. 1 follows an ERA in Nevada two years ago, which passed with 58 percent of the vote after being pitched to the state’s fiercely independent residents as a means of protecting individual liberty. The Nevada ERA overcame opposition from anti-abortion forces—including the religious-right legal firm Alliance Defending Freedom—which predicted that the measure would void Nevada’s ban on Medicaid coverage for abortion. (It was right.) Next up: An expansive ERA is slated for the 2026 ballot in Minnesota, and another is on the table in Oregon. “It’s incremental,” Cheng says. “Every state that does something new, it creates a new bar or a new precedent for other states to go beyond that.”

These amendments work in two ways. First, they harden the state’s existing constellation of anti-discrimination laws by adding them to the state constitution. And second, they give individuals strong constitutional grounds to challenge discrimination by the government. In New York, Prop. 1’s protections for different “pregnancy outcomes” might be used to defend women from criminal prosecution after self-managed abortions or losing a pregnancy in a car accident—both of which have happened in New York, says Dana Sussman, senior vice president of Pregnancy Justice, a nonprofit legal advocacy group. And it might be used to challenge state hospitals that drug test pregnant women, sometimes without their knowledge or consent—policies that can lead to child protection cases and family separation.

Other activists hope the ERA could be used to overturn the state’s 24-week gestational limit, which forces some New Yorkers to travel out of state if—for one of the many reasons women can face delays in accessing care—they need a later abortion. Randi Gregory, vice president of political and legislative affairs at the National Institute for Reproductive Health Action Fund, believes Prop. 1 would protect abortion rights “at all trimesters.” “We hope that it will be a framework for other states,” Gregory adds. “We’re really excited to be running an expansive and proactive amendment.”

But that’s only if they can get it passed—a task that looks increasingly daunting.

The coalition behind Prop. 1 made big promises in June 2023, after New York Democrats’ embarrassing showing in the 2022 election. Their losses had helped flip control of the US House of Representatives back to the GOP, while former US Rep. Lee Zeldin, an anti-abortion Republican, came within 6 points of winning the governorship.

State Democrats evidently had an excitement problem—one they hoped the ERA could solve. Gov. Kathy Hochul and Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand told the New York Times that they wanted to use the amendment to motivate 2024 turnout. Progressive groups formed New Yorkers for Equal Rights, a committee that pledged to spend $20 million ginning up enthusiasm.

Yet in early September, Politico reported that the committee had raised less than $3 million to counter an opposition that had proven surprisingly well-organized and effective. Suddenly, Democrats were afraid of how Prop. 1 might affect their candidates in tight races. In the ensuing scramble, Hochul announced $1 million for TV ads and direct mail and issued a statement: “It’s critical voters know that an abortion amendment is on the ballot in New York this year,” she said. “New Yorkers deserve the freedom to control their own lives and health care decisions, including the right to abortion regardless of who’s in office.”

The opposition campaign, the Coalition to Protect Kids, is largely funded by an upstate anti-abortion activist, Carol Crossed, who is vice president of Feminists Choosing Life of New York. Yet it has leaned heavily on anti-trans rhetoric, arguing the amendment would increase trans people’s access to girls’ sports, women’s bathrooms, and gender-affirming medical care—and that these things would be dangerous. “Anti-abortion extremists are pushing a harmful and cruel agenda,” says Sasha Ahuja, campaign director for New Yorkers for Equal Rights. “They’re lying about a small handful of innocent kids to divide New Yorkers and distract us from what this amendment is actually about: protecting the right to abortion, guaranteeing our personal freedoms, and protecting all of us against government discrimination.”

“They’re lying . . . [to] distract us from what this amendment is actually about: protecting the right to abortion, guaranteeing our personal freedoms, and protecting all of us against government discrimination.”

According to New York politics magazine City & State, internal polling shared with ERA proponents in late August found that 64 percent of voters would definitely, likely, or lean toward voting yes on the amendment when presented with its ballot language. But support plummeted by 24 percentage points after voters heard an attack message focused on girls’ sports, transgender protections, and immigration. (Another blatant lie spread by opponents is that Prop. 1 would allow undocumented immigrants to vote.)

Ilyas believes the anti-trans messaging gains credence because many voters don’t have personal experience or relationships with trans people. “When you don’t know a trans person, you have this well-funded messaging at you, and people that you trust are saying the same exact thing and reiterating it, it makes sense for even the average New Yorker who’s middle of the road to believe it,” Ilyas says.

Anti-trans attacks have become a go-to strategy for conservative groups fighting abortion rights ballot initiatives. Opponents to Ohio’s abortion rights measure last year claimed it would permit minors to undergo gender-affirming surgery “without parents’ knowledge or consent” and dubbed it an “anti-parent amendment.” (Such surgeries for minors are very rare, and consent from parents or guardians is required.) In Missouri, a last-ditch lawsuit in September tried to block an abortion rights measure from this fall’s ballot by arguing that it might affect laws around single-sex bathrooms and that the voter petition should have disclosed that. (The state Supreme Court didn’t buy it.)

In New York, Prop. 1 supporters have repeatedly pointed out that the amendment says nothing directly about trans participation in sports. In fact, trans inclusion in sports is already New York’s status quo, thanks to existing anti-discrimination laws and a state policy allowing trans students to participate on sports teams matching their gender identity. But like Phyllis Schlafly, Prop. 1’s opponents love a dire warning: Lawn signs saying, “Save Girls Sports, Vote No Prop 1,” have become a regular sight in some areas. Republican politicians have been picking up on the theme, including Zeldin, the former congressman, and Gina Arena, a GOP candidate for the state Senate from the lower Hudson Valley.

On Long Island, Nassau County Executive Bruce Blakeman and the Republican-dominated county legislature passed a law this past summer blocking permits for women’s sports teams that include trans women, preventing them from using more than 100 county-run parks and athletics facilities. In response, the New York Civil Liberties Union sued the county on behalf of a women’s roller derby league, citing existing New York civil and human rights laws that forbid discrimination based on gender identity, sex, and disability. If the ERA was in the state constitution, lawyers for the league would doubtless argue that Nassau County had violated it as well. “Transgender athletes have been competing and allowed to compete in the state for a really long time now,” Cheng says. “That’s not going to change because of the ERA.”

“Transgender athletes have been competing and allowed to compete in the state for a really long time now. That’s not going to change because of the ERA.”

Still, uncertainty around which laws the ERA might challenge has been a boon to opponents. On its website, the Coalition to Protect Kids claims that banning age discrimination, for instance, would gut laws governing the drinking age, statutory rape, and parental consent for minors to receive medical treatments—especially gender-affirming care. Bodde dismisses these arguments as “misinformation” meant to “stir fear.” Courts have been clear that constitutional rights apply differently to minors and adults, she says, even despite laws forbidding age discrimination. “The state has long been able to create different rules when it comes to young people, whether that’s ensuring a certain age before people can learn how to drive or vote or purchase alcohol.”

But fear and confusion are powerful tools. Prop. 1’s opponents have dubbed the ERA the “Parent Replacement Act.” On social media, the Coalition to Protect Kids has repeatedly cited the American College of Pediatricians, a misleadingly named fringe group of anti-LGBTQ doctors whose frequent declarations against gender-affirming care run counter to the conclusions of dozens of major medical associations. Sometimes the claims slip into self-parody: “If Prop One passes…children will mutilate themselves without the benefit of parental guidance,” reads a mailer sent to voters by the New York Republican State Committee.

For Ilyas, who is transmasculine, the extremist rhetoric feels very personal—and deeply worrisome. “People don’t think that it could happen in New York, just because it’s New York,” Ilyas says. “These people do exist in New York, and they just maybe haven’t had an outlet.”