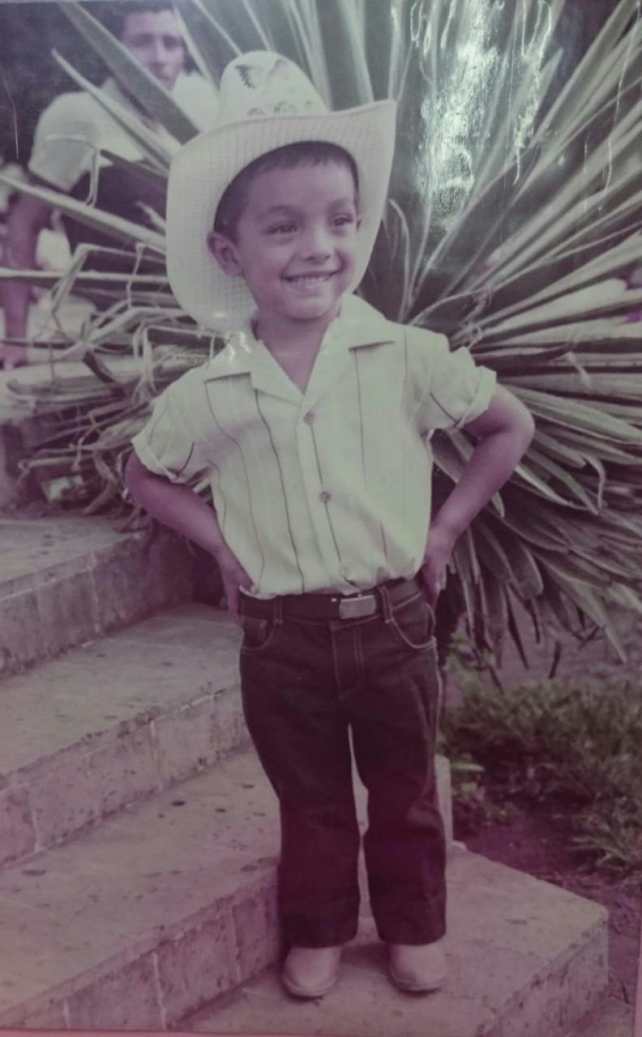

Carlos Sauceda called the United States home for 27 years, more than half of his life. In 1992, he left Honduras as an 11-year-old boy to reunite with his mother, who had moved north when he was just 18 months old. Sauceda grew up in Los Angeles as a green card holder. He was surrounded by classmates and neighbors who were involved in gangs. Sauceda was drawn to the sense of belonging and camaraderie the gang membership provided. At the age of 15, having to prove his loyalty to the gang, Sauceda shot and killed someone he suspected was part of a rival group. He was arrested, prosecuted as an adult, and pleaded guilty to second-degree murder. In 1997, he was sentenced to 15 years to life.

From one perspective, Sauceda’s crime could reduce him to the stereotype of Donald Trump’s anti-immigration poster child. But that is where his story diverges from the dangerous-immigrant trope. While incarcerated, Sauceda quit the gang and became a certified alcohol and drug studies specialist and mentor for at-risk youth. He earned his GED and a college degree. In 2008, another inmate at California’s Ironwood State Prison, which is located between Los Angeles and Phoenix, Arizona, introduced him to one of his relatives, a woman named Yahaira. She was born in El Salvador and moved to the United States with her mother in the 1980s when she was four years old. Eventually, she became a US citizen.

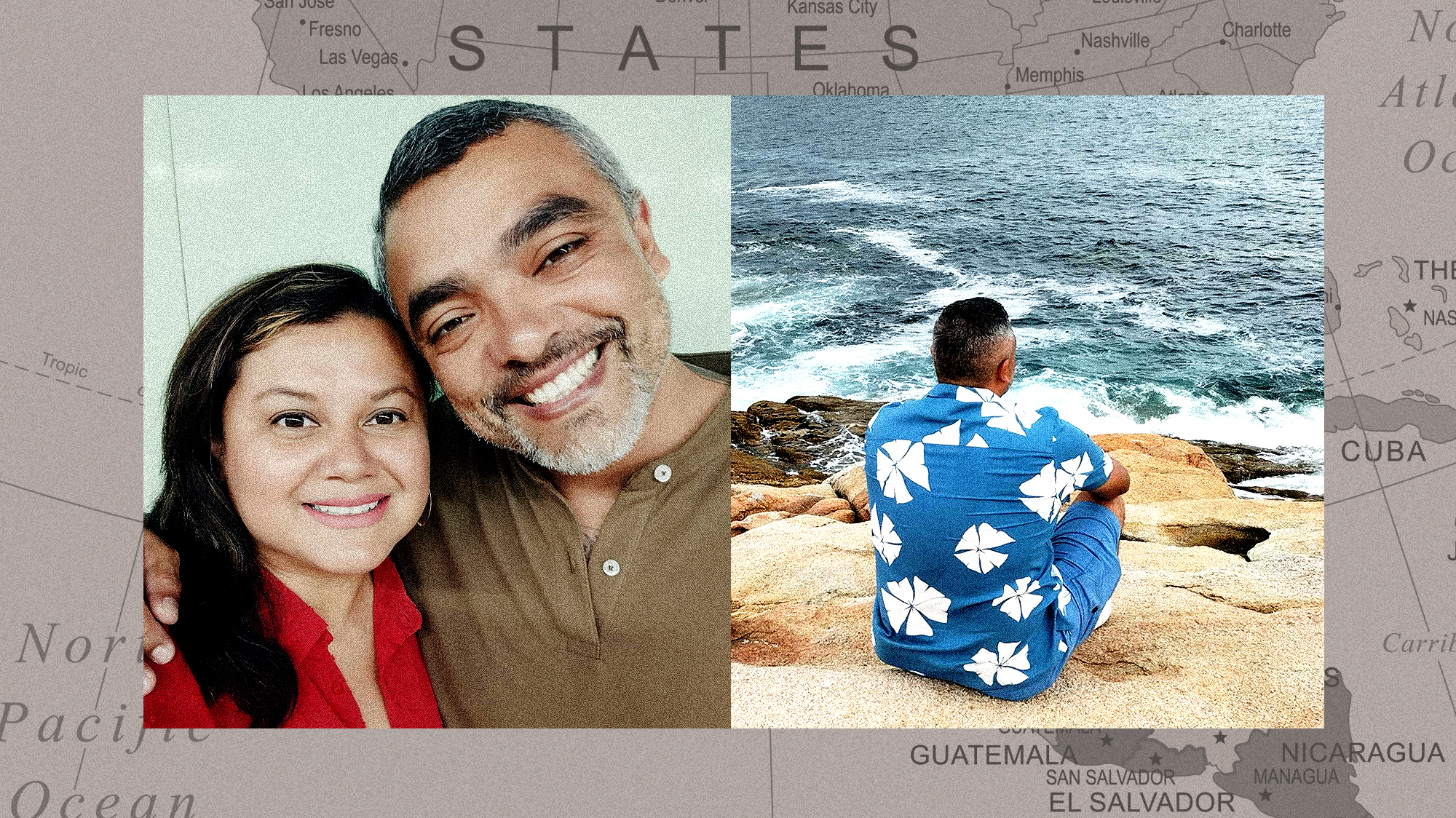

“I would love to tell you it was love at first sight,” Yahaira tells me, laughing, “but it wasn’t.” They began as friends. Exchanging letters about their faith, she would tell him about her church volunteer work. Soon, their talks during visitation went on for hours. Seven years later, in 2015, they got married in prison. “One thing I noticed about Carlos was that although he was physically imprisoned,” she says, “his mind was always free.”

Then in July 2017, after serving 22 years, Sauceda received a second chance when the California Parole Board granted him early release due to his rehabilitation. But on November 17, 2017, instead of becoming a free man able to finally build a life with his new wife, he was shackled and transported to an ICE office where he was placed in deportation proceedings. As a result of his criminal conviction, Sauceda lost his green card. “You’re never going to get out of detention,” an agent told him.

Even though the Trump administration had supercharged immigration courts with judges geared towards deportations, in September 2018, a judge granted Sauceda protection from deportation under the Convention Against Torture after finding that he faced “a clear probability of torture in Honduras.” Sauceda, whose body carries gang-related tattoos, had met higher standards than those required of asylum claims.

Still, the government appealed the judge’s decision and the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) granted it. Sauceda was trapped in a lengthy bureaucratic process—and remained in detention until he finally gave in and returned to Honduras in 2019. Soon his relatives warned him he would have to flee before he was killed. In August 2021, he went to Europe, which is where he and Yahaira now live, still fighting to come back to the United States.

Carlos Sauceda as a child.

Courtesy of Carlos Sauceda

Sauceda is one of an indeterminate number of immigrants who have been deported to often dangerous places, but who may have a legitimate claim to return to the United States. Many have lived in this country longer than anywhere else. They have started businesses and parented US-born children. Some, like Sauceda, have come in contact with the criminal justice system, triggering a double punishment in the form of immigration detention and deportation, often as a result of convictions for non-violent offenses such as marijuana possession, which is no longer criminalized in some states. Those facing deportation on criminal grounds are disproportionately Black and Brown immigrants.

Nayna Gupta, associate director of policy at the National Immigrant Justice Center (NIJC) and a former immigration defense attorney at California’s Alameda County public defender’s office, has been the leading advocate in a campaign to remedy wrongful and unjust deportations. In 2021, she authored a white paper calling on the Biden administration to establish a fair process to return people deported under previous administrations. This June, the organization launched the “Chance to Come Home” campaign in cooperation with deported advocates and partnering with legal and immigrant rights organizations.

Generally speaking, deported immigrants attempting to return might seek a review of their deportation order with the federal courts. Or they can ask an immigration judge to reopen a case within 90 days of being ordered deported to make new arguments and try to overturn a final order of removal. In some instances, these immigrants have benefited from reforms to the criminal justice system. “Yet, on the immigration side,” she notes, “they’re still stuck living in exile.” For those like Sauceda, whose criminal convictions are, on its face, less “palatable,” Gupta says, “everything is an uphill battle.”

When I meet Gupta at a coffee shop in Northwest Washington, DC, one Friday afternoon in August, she hands me three sheets of paper. One of the leaflets shows the faces of 10 people, including Sauceda. Next to their names and photos are attributes that define many American citizens: mother, father, husband, brother, son, entrepreneur, living with a disability, teacher, survivor, and breadwinner. While NIJC’s campaign represents only ten individuals, Gupta says, “They represent thousands of people.”

“Congress envisions that there is a way to remedy a wrong or unjust deportation,” she says, “but those mechanisms don’t work in practice.” ICE narrowly applies a 2012 policy to facilitate a person’s return from wherever they were deported in cases where they need to be present in the United States to continue to fight their case, or if they have a claim to a green card. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) rarely grants such requests, which are difficult to make in the first place, especially without legal representation.

“These are discretionary decisions that ICE officers can be making to help people be with their loved ones,” Gupta says. “But an agency like ICE is oriented towards detention and deportations and so they shouldn’t be asked to make these decisions.” Instead, she argues, there should be an independent office—similar to Conviction Integrity Units in prosecutor’s offices in the criminal justice context —under the authority of the Homeland Security secretary to process post-deportation return applications.

“In a system that has deported 2 million people in 10 years, obviously there are some bad decisions,” Gupta says. “How can you have a remedy process that doesn’t work?”

When Gupta first took on the campaign back in 2021, she was skeptical of its viability. “We can’t legalize 12 to 15 million people living here,” she says. “We can’t get lawful pathways for DACA people. Who is going to care about deported people?” But after the original white paper came out highlighting the stories of 11 deportees, six of them were allowed to return.

One of them was Howard Bailey, a US Navy veteran who was arrested in 1995 for marijuana possession. He was 22 years old and had served in Operation Desert Storm in the Middle East. His lawyer persuaded him to plead guilty, and he did, unaware of the immigration consequences. Years later, when Bailey applied for US citizenship in 2010, he disclosed his old conviction and his application eventually was denied. One day, ICE agents picked him up at his home in Virginia. After two years in detention, he was deported to Jamaica, a country he hadn’t seen in more than two decades. There, Bailey, who had a thriving trucking business in the United States, tried to make a living as a pig farmer, away from his wife and children. Finally, in 2017, the year Virginia legalized adult recreational use of marijuana, Virginia Gov. Terry McAuliffe pardoned him.

Nayna Gupya with Howard Bailey after his citizenship ceremony.

Petula Dvorak/Courtesy of Nayna Gupta

“I was a happily married man, with two American kids, and a home I purchased with my VA loan,” Bailey testified in a Senate Judiciary subcommittee hearing in June 2021. “I owned my own trucking business with four employees and paid my taxes. In my mind, I was living the American dream.” Since being deported, he said, “Life feels like a total nightmare.” His business closed, his marriage fell apart, and his children struggled in school.

Still, Bailey turned out to be one of the lucky ones. His case drew media attention and support from members of Congress, and DHS—now during the Biden administration—agreed to reopen his case. He was able to come back through a process known as humanitarian parole. In August 2021, when he arrived at Reagan National Airport in Washington, DC, Gupta was waiting alongside his family. “It’s one of the top three experiences of my life,” she says. The Customs and Border Protection agents who escorted Bailey off the plane applauded him, and Gupta recalls that he had asked if it was a setup. “What does it say about the system of rule of law if for 10 years you said ‘no’ and then all of a sudden one day you just flew him home and all clapped for him?” She was also there when Bailey became a US citizen in June 2023.

The Biden administration reportedly made noncitizen veterans and relatives a priority in their quiet plans to address excessively harsh deportations from previous years. In July 2021, the administration announced the Immigrant Military Members and Veterans Initiative, an effort to return some of what advocates estimate to be hundreds of deported veterans. Since then, DHS has allowed 82 veterans back. While imperfect, the program is a “proof of concept,“ Gupta says. “We know they can do it.”

Gupta started hearing from dozens of people stranded abroad and family members hoping to bring their loved ones back. Eventually, ten people became the face of the NIJC’s campaign. She has come to know their stories intimately and speaks passionately about the nuances of each individual case. The campaign has garnered the support of 64 members of Congress so far. Now Gupta hopes they will get a meeting with DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas. But with the looming 2024 election, she feels the urgency of their work. “These 10 people are very aware of the fact that this [campaign] hinges on who’s president,” she says, “who’s in power.”

Nayna Gupta talks about the Chance to Come Home campaign at Netroots Nation.

Courtesy of Nayna Gupta

Assia Serrano is one of those people. In 2003, she was 19 and controlled by an abusive partner who was 20 years her senior. She robbed an 85-year-old woman who had been one of her clients when she was a home health aide. The woman later died as a result of a blood clot caused by having her hands tied against her stomach. Serrano pleaded guilty to second-degree murder and was sentenced to 18 years to life in prison. She had a baby daughter at the time and gave birth to her son while incarcerated, but was only allowed to care for him for two days. The children went to live with their father, Serrano’s ex-partner.

In 2021, after 17 years in prison, Serrano became one of the first people to have their sentence reduced under New York’s Domestic Violence Survivors Justice Act. The law, which passed in 2019, provides relief to survivors whose abuse played a role in their offense. “The very same court system that ordered her to prison later recognized that the only reason she got caught up with the criminal punishment system in the first place is because she was surviving domestic violence,” Serrano’s lawyer Nathan Yaffe says.

Serrano, then 37, and her daughter started making plans for when she got released: Going out for dinner, getting their nails done, going shopping. “Things that we never got the opportunity to do together,” she says. “Still haven’t had the opportunity.”

Unbeknownst to her, she had a deportation order and after walking out of prison, she was immediately transferred to ICE custody. On June 17, 2021, Serrano was deported to Panama, where her 87-year-old father with early-stage Alzheimer’s is her support network. She is currently challenging a denial of a motion to reopen her case, but a pardon from New York Governor Kathy Hochul is her best bet.

She talks to her children, now 19 and 18, on Facetime every morning. To feel closer, she follows them on all social media channels and they share their locations so she can know when they are home. “My children have been in a constant state of waiting,” she told me. “Every time I have to explain to them it can’t happen now; I feel like I keep letting them down. I made mistakes and I pay for those mistakes every day of my life thinking my children will live without me.”

When I call Sauceda in mid-June, he tells me his wife, who usually keeps her worries to herself, has been having a difficult time. “It’s tough on her because all her family is in the United States,” he says, “and she has always been very close to her family.” On the day we spoke. she had confided that she really wanted to leave Europe and go home to Lancaster, California. “I just don’t know how much longer we have to wait,” she told him.

In September 2020, Yahaira received a frightening diagnosis after almost passing out at work and being rushed to the hospital. A CT scan and a cerebral angiogram test revealed five bilateral internal carotid artery aneurysms in her brain. Yahaira was advised that because of the size and location of the aneurysms, she would have to undergo at least one surgery—if not two or three. There was also the risk of ruptures that could cause a stroke or even death.

Sauceda was in Honduras at the time, the Covid-19 pandemic raged, borders were closed, and Yahaira, was the couple’s breadwinner. She was working at a bank and realized that she would have to postpone the surgery. When Sauceda fled Honduras to Europe in August 2021, Yahaira followed him soon after. “She didn’t want to be separated from me any longer,” Sauceda says, “and that’s why she made the choice to say, ‘I’m going with you.’ She really believed that justice would be on our side.”

As a deportee, Sauceda’s struggles became intertwined with a larger cause, one that had been years in the making. After he was picked up by ICE in 2017, he was sent to the Yuba County Jail in Marysville, 40 miles north of Sacramento in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada. When he describes it, he uses words like “psychological torture” and “inhumane treatment.” There were the bugs and gnats in the shower, the cells lacked drinking water or lights, and officers who made detainees feel less than human. Pleas for medical care from cellmates with broken fingers and cancer-induced pain were ignored. When Sauceda’s blood pressure rose to life-threatening levels, his only thought was, “I cannot die in here.”

In time, depression and suicidal thoughts set in. “It was the worst and most painful feeling, because I had to decide if I wanted to die in a detention center,” he says, “or if I wanted to give myself the opportunity to be free and at least have the chance to run…I didn’t want my mother to have to go get me in a box at a detention center.” As he would later write in an opinion piece for the San Francisco Chronicle, “The two years I spent there awaiting a decision on my immigration status were far worse than the over two decades I spent in 12 different prisons serving out my sentence.”

The jail had a history of violations going back to 1979 when a federal court ordered it to operate under a consent decree to improve conditions—including mental health and medical care, exercise and recreation, and staffing issues—for inmates in response to a class action lawsuit. Years later, in 2016, lawyers representing inmates at Yuba reported about 40 suicide attempts in a two-and-a-half-years period, earning it the moniker of “suicide jail.”

While in detention, Sauceda staged three hunger strikes denouncing, among other things, the lack of medical care. In February 2019, he says ICE retaliated by moving him to Mesa Verde, a detention center five hours to the south. “At that time, I didn’t know that what we were doing was organizing,” Sauceda told me. They also found support on the outside, where advocates were doing rallies and making calls to pressure ICE. “It was just very organic,” says Susan Lange, a coordinator with the volunteer visitation group Faithful Friends. “They had to grow and learn to trust us.”

During his exile, Sauceda continued to speak up about his experience in detention and joined a liberation coalition effort to close the Yuba County Jail. In the face of the health risk posed by the Covid-19 pandemic and as a result of community organizing and successful class action lawsuits, Yuba’s immigrant detainee population began to dwindle until the last person was released in October 2021.

“Detention closures don’t just come out of the blue,” Edwin Carmona-Cruz, co-executive director of the California Collaborative for Immigrant Justice, says. The campaign’s success is a testament to an infrastructure of community-legal partnerships involving attorneys, local organizers, and directly impacted people like Sauceda. The detention center was briefly repopulated. But in December 2022, ICE sent Yuba County a notice of termination of their agreement—which was set to expire in 2099 and awarded more than $8.6 million a year to the county. Two months later, the contract officially came to an end.

“When you have victories like the ending of the Yuba contract,” Sauceda says, “it gives you hope because it gives meaning to this suffering. Even if I don’t get to see the blessing, I hope other families don’t experience what my wife and myself and my family are going through.”

Meanwhile, for five years, Sauceda has been fighting his immigration case. He even won an appeal with the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, which sent the case back to the BIA; they changed their original decision and reaffirmed the immigration judge’s grant of protection. Had Sauceda been in the United States, the government wouldn’t have been allowed to deport him. Because he isn’t, he has a narrow path for returning. Especially since ICE has denied a request to provide the travel document that would have allowed Sauceda to re-enter the country.

“There’s no court case that you can bring to force ICE to give you permission to return to the United States,” says Minju Cho, an attorney for the Immigrants’ Rights Program at the American Civil Liberties Union of Northern California representing Sauceda.

Now, his future may hang not on ICE’s will, but on Governor Gavin Newson of California. A pardon grant from the governor, Cho explains, would allow them to make a case in immigration court that Sauceda’s single criminal conviction—and the basis for his deportation—no longer legally exists and, therefore, the removal order should be terminated and his green card restored.

“He won final protection from deportation from the US judicial system over a year ago,” Cho says. “There’s no reason he should be abroad right now fighting to come back.” In a letter supporting Sauceda’s January 2023 petition, she wrote that Sauceda “represents and affirms what I believe about people in my heart of hearts—that people are capable of profound change. That people are the product of their choices, yes, but also their circumstances. That people are more than the worst thing they have ever done.”

The first few months in Europe were difficult for Sauceda and Yahaira. They got by with the help of US-based volunteers and advocates and found a place to stay through a person they met in church. Yahaira, who had a career in banking back home, takes all the odd jobs she can find cleaning houses, ironing clothes, walking dogs, and babysitting. The doctor said she needs to watch her stress levels, which isn’t always easy.

Still, their photos on Facebook show an inseparable couple, forever in a honeymoon phase. “We’re learning how to be there, in health and sickness, richer or poorer, in one country or the other,” she says. “We’re finding beauty in the ashes.” To Yahaira, it felt at times like she had to choose between her family and her husband. An only child, she talks to her mother daily. The “pain and the agony” of separation stamped on her mom’s face mirrors the pain and agony she feels. At the end of another day, Yahaira is left wondering, when is this going to be over?

Recently, Sauceda applied for humanitarian parole, which would allow him to wait for a decision on the gubernatorial pardon in the United States. “My fight goes beyond just myself,” Sauceda says, “It’s for my family, for my wife, and for everybody that has gone through this type of process—because it really victimizes families.”