On the day before America decides whether to go full fash, we wanted to provide you with reading material to reflect the prevailing moods of the moment. After careful study and deliberation, we have determined those moods to be “fuck,” “fuck this shit,” and “fuck…yeah?” Put another way: anxiety, fury, and hope.

But we realize you might not be eager to read anxious words when you’re feeling hopeful, or furious words when you’re feeling anxious, or hopeful words when you’re writing National Lawyers Guild phone numbers on your forearm. So, flush with the democratic spirit, we’ve left the choice of what to read to you.

Whatever mood you’re in at the moment, click on the corresponding buttons below to see all the things making Mother Jones staffers anxious and/or furious and/or hopeful right now. Come feel weird with us, America! We’ll see you on the other side.

How are you feeling?

Filter by tag

Choose your

mood above

Anxious

As Instagram would have it, people the world over have used pandemic quarantine to get ripped or learn to paint or bake sourdough. Alas, I have done none of these. Instead, the new pandemic habit I’ve picked up is a lot less fun—and probably a lot less healthy. Reader, I can’t stop checking my bank account.

There is no rational reason for this. Nothing about the activity in my bank account is new, exciting, or terrifying enough to warrant my visit frequency. I’m employed, an enormous privilege in these uncertain times. I know exactly when my paycheck will show up and exactly when my rent is due. My bills are on autopay. I have not suddenly come into money from a secret inheritance (though wouldn’t that be nice).

The truth is, watching numbers in my bank account move exactly as I expect them to is the weird adult self-soothing that’s getting me through this it-might-not-end-for-another-year pandemic life. It feels like the one economic reality that I have some control over, as I’ve helplessly watched the financial stability of millions of Americans, including family and friends, deteriorate in real time.

The scale of that deterioration is enormous. We’re eight-ish months into the pandemic, and the federal government has given (some) people $1,200. The lifeline that was the $600 weekly unemployment boost expired three months ago. At least 12.6 million people are still unemployed and another 4.6 million furloughed. Many households’ savings are dwindling or gone. Nearly 20 percent of adults say they don’t have enough food. Millions of renters are existing beneath roofs on borrowed time, insulated from eviction until the end of 2020 by a CDC moratorium, but what comes after is a giant question mark. The COVID economic recovery that Trump keeps boasting about is mostly benefiting the ultrawealthy.

Making matters worse, there doesn’t seem to be relief coming anytime soon. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell adjourned the Senate last week after confirming a new Supreme Court justice but before lawmakers could pass a new COVID relief package. Just a few days later, Speaker Nancy Pelosi, the Democrats’ lead negotiator on a relief package, sent Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin, the Republicans’ lead negotiator, a letter laying out the many, many areas where they still need to find agreement.

It all feels like a gut punch. And right now, regardless of who becomes president, I don’t know how we come back from this. There is also part of me that thinks we were only just here, on the creaky merry-go-round that is Uncertain Financial Times in America™.

Some days it feels like most have us have actually been here our entire lives. I’m the child of immigrants, the daughter of a working-class single mom, and a millennial who graduated from college in 2009, straight into the Great Recession. On graduation day, almost none of my friends had jobs, while some had six-figure student loan debt. Our commencement speaker, political commentator Fareed Zakaria, gave a speech in which he told us that despite global financial concerns, he was, and I quote, “not at all pessimistic.”

Now we know just how much there was to be pessimistic about: years of lingering financial struggle that sowed fear, dismay, and a desire to blow up existing structures that arguably helped give us Donald Trump.

I wonder what unforeseen financial and political chaos still awaits us as a result of this terrible economic moment. Looking back at the years since the last recession, at my family and friends who feel like they’ve only just recovered, I can’t fathom the problems we don’t know about yet, nor can I fathom doing the last decade of post-2008 rebuilding all over again. So for now, I guess I’ll just channel my anxiety into the tab on my browser that takes me to my bank account. To be honest, I don’t know where else to look. —Hannah Levintova

Most afternoons my dog Cooper asks to go out to the patio to soak up some sun, no matter how hot it is outside. Sometimes I join him and try to get a bit of fresh air and sun myself. One of those afternoons last month, I stood outside and felt the sweltering heat on my face, as I watched my dog do his thing, and like an avalanche I had a mini freak out about climate change. It was October and it was over 100 degrees in Tucson, Arizona. The average high temperature in early October is around 90.

We had recently moved back to Tucson, where I had lived for over a decade. After being in New York City and Los Angeles, I thought maybe I had lost my desert rat status and could no longer handle the heat. But it turns out that we had moved back during the hottest August on record in Tucson and other cities across the state. Tucson also had the second-driest monsoon season ever, meaning the short window when we get rain in the summer months didn’t relieve us from the heat. September was also disgustingly hot, and October started out breaking more records, too, with the hottest October 1st temperature ever in Tucson, at 103 degrees.

So, while I stood on the patio during what is normally a nice and necessary break from it all, I grew legitimately and urgently concerned about the future of places like Arizona. I’ve always known how big a deal climate change is on an intellectual level, and I’ve seen and read the work of my colleagues on the devastating fires, hurricanes, and other natural disasters made worse by climate change, but there was something about imagining just how much hotter it’s getting here, year by year, that made me panic that day. I was suddenly and uncontrollably anxious about the many environmental regulations the White House has rolled back, about the lack of action from global leaders to address the climate crisis, about the communities who don’t have access to relief or protection from extreme heat or extreme cold.

After about 10 minutes outside, I started to sweat and feel the heat a little too much, so I walked back indoors and cranked the AC. Yes, I knowwww that overuse of air conditioning is contributing to the same problem I’m anxious about, but damn it’s impossible to get through a work day at home when it’s too hot to function.—Fernanda Echavarri

My amygdala should have blown up by now, like some engine that is overheated, steam pouring out of the hood (or my ears), pulled over by the side of the expressway. Sold for parts. Or maybe it should have just collapsed into some cringing and exhausted heap, no longer capable of monitoring my emotional register, of triggering the fight-flight response it’s so famous for managing.

If my amygdala were truly protective of me, it should just say fuck it. These years and years of Trump-induced anxiety has been too much to deal with for anyone, this evolutionary adaptation has met its match.

The amygdala is a little almond shaped part of the brain—the name actually comes from the Greek word for almond—and its all about managing our emotional state, especially when it comes to anxiety and uncertainty. It’s focused on the future, the panicky little voice saying, “Watch out! It looks risky! Did you think of what this storm approaching could mean? Batten down the hatches! Those trees near your house will destroy your roof. The president of your country will destroy democracy.” You get the idea.

Which brings me to why mine, why everyone’s I suppose, is exhausted after all these damn years of watching institutions crumble, a group of politicians become enablers for crypto-fascist leadership, children put in cages, their parents lost (Lost?? When will the trials for crimes against humanity begin?), our Cold War foe becoming our frenemy, the overt racism, the grotesque abuse of government workers. Absolutely everything is implicated. And anxiety is washing over my perceptions of absolutely everything.

I am anxious about getting COVID. About someone in my family getting COVID (right, my daughter already had it); ok, about my daughter getting sick again. I’m anxious about insomnia and about the reason for it, about my 15-year-old dog dying, about typos (even worse if they’re in the hed or dek). I’m anxious about climate change. There’s my gas stove, anxious about that because I am reading so much about how bad they are, plus we should include anxiety about my excessive consumption of paper towels.

I am anxious about falling down stairs and driving over the Bay Bridge and not going swimming and going swimming. I am anxious about something happening to my house or my car or my 401k (ok, something happened, it’s fine). I am anxious about the winter and quarantine when it’s cold and dark and all those delicious distant dinners and drinks al fresco will be impossible. I am anxious about getting a heater for outside and anxious about propane, about Mercury in retrograde, about Fauci’s health, about the criminal in the White House, about the mess we are in, about a huge economic depression and a national nervous breakdown. I am anxious about QAnon and about some people in my neighborhood who are actually buying more food or leaving town to go to Arizona of all places because they are worried (make that anxious) about a civil war after the election. I am anxious about not having solar panels. I am sick with anxiety about how we’ve forgotten about the kids in cages and what will happen to them?

What has happened to them?

What has happened to us all?

What is the point of all this anxiety? I talked to a Hungarian friend who lives in Germany the other day. He said, with the fatalism of Hungarian Jews that I know so very well, “Stop worrying. Nothing matters.” I think his amygdala has just thrown in the towel.

Except, it does matter. It matters so much, it makes me anxious. —Marianne Szegedy-Maszak

I live in the southern edge of San Francisco, near Jerry Garcia’s childhood home, where gathering places are few and far between and, judging by the line, Friday night’s hottest ticket is a seat at Popeyes. So when Excelsior Coffee opened in 2019, the sleek new spot quickly became the talk of the neighborhood. The young owners emblazoned the front window of their shotgun Mission Street space with proud gold-letters and a local artist bedecked the top of the building with a geometric mural. A motorcycle is parked on a shelf overhanging the communal table, and the walls are plastered with photographs of the neighborhood’s past.

The espresso is always smooth, the Saturday morning breakfast sandwiches have ’90s hip-hop inspired names—try the Missy Eggliot—and every day the pastry case boasts fresh Filipino-inspired tarts flavored with ube and pandan. The welcoming staff give the intimidatingly hip café a cozy and communal vibe. Even with our masks muffling our words, I trade film recommendations with the baristas (Albert suggests The Black Power Mixtape) or fall into spontaneous discussions about city politics with people in line.

And then the shutdowns were imposed nearly everywhere (for very justifiable public health reasons), and I found my anxiety spiking when I considered the fate of independent businesses like Excelsior Coffee. Just two months into the pandemic, the number of people owning small ventures had nosedived by 22 percent, and it sadly should come as no surprise that immigrant, African-American, Latinx, Asian-American, and female-run businesses suffered disproportionate losses.

It is too easy to contemplate how this will all turn out without a federal strategy to care for people working in these types of small ventures. As the pandemic lingers, the absence of a national mask mandate and frequent testing makes COVID-19 spiral even more out of control, sickening millions of servers and store clerks. A lack of federal stimulus will force most small shops to shutter. Then, it’s just a matter of time, assuming no larger intervention, when workers at small employers will lose the social safety net of Obamacare and ditch small workplaces in favor of large corporate conglomerates. Immigrants who own and staff many of the Bay Area’s best independent restaurants may end up being forced to flee the United States because of its hostile culture and policies.

If a successful vaccine ever arrives, chains will have taken over, eclipsing cityscapes with their jewel-toned billboards and forced anodyne slogans. My lunch options will consist of Chipotle, Popeyes, and Sweetgreen. Rather than walk to the leather store to get my boots fixed, with a stop at the Italian bakery for an almond cookie on the way home, I’ll remain in front of my computer screen and send the boots out for repair via Amazon drone. (Research by Adobe shows that people spent more time online in April and May than they did during last year’s holiday splurge season.)

When I want to buy a new book, my only option is to log onto Amazon because all brick and mortar bookstores will have been swallowed whole by this evil jungle, and along with them their handwritten recommendation tags, social-justice inspired children’s books, weekly author readings, and MFA students working the cash register, who clearly judge my Outlander purchase but whose eyes light up when I ask if Maggie Nelson’s Bluets would be filed under nonfiction or poetry.

How could places like Excelsior Coffee stay afloat? They can’t. The only cafés that manage to stay open serve barely palatable dark roast and blast either Norah Jones or Kanye from their speakers every day, every month of the year—because they’re all owned by Starbucks. (Playlist available for purchase along with your seasonal latte.) A future far bleaker than even the worst coffee withdrawal headache. —Maddie Oatman

Full disclosure: I have always been anxious. In the Before Times, I lived with the constant hum of nervousness, like a gnat buzzing around my ear. I’m terrified of cliffs, snakes, trees wider than two feet in diameter, and any medical procedure that is even remotely invasive, to name a few.

And then 2020 happened, and my anxiety gnat became a murder hornet buzzing like a jet engine. My list of fears grew to include my aging parents getting sick, overcrowded grocery stores, job loss, public transit, private helicopters, armed militias, wildfires, earthquakes, and the biblical flood that will likely decimate California (shoutout to my colleague, Tom Philpott, for that one).

Now, after eight months of sheltering-in-place, I’ve managed to get anxious about my anxiety. My latest fear is that the world will go back to normal, and I just…won’t. I’ve adapted to life indoors, where things are safe, albeit a little stuffy. I imagine myself 30 years from now, writing articles from the tiny desk I panic-built in the early days of the pandemic and Zooming my loved ones during their IRL happy hours. If they ask why I won’t join them, I’ll mutter something about inadequate ventilation, then make an excuse to hang up so I can feed my sourdough starter and water 50 half-dead houseplants.

What if I never shake another person’s hand again? What if I never eat in another restaurant? What if I never go to another concert or wedding? What if I stay home until I die? And what if I don’t mind?—Laura Thompson

In the summer of sequester, my front porch was my saving grace. It’s not what you’d call a “nice” porch. The table is a decaying Ikea desk that a friend repurposed with a couple of two-by-fours laid across the top. One of the chairs has a hole in the mesh seating from a sparkler mishap. It’s cluttered with baby detritus: the aspirational Exersaucer where my wife and I once imagined our 1-year-old patiently playing while we work alongside him (ha!), the scooter we use to push him up and down (and up and down) our 12-foot front walkway. But this summer, it was the most important place in our lives. It was where we hosted socially distant dinners, played a few tunes while our son napped, chatted with neighbors, and washed away the long days with an 8 p.m. nightcap.

But as the leaves and the temperature begin to drop and it sits increasingly idle, my front porch has become a reminder of the brutal winter ahead: the cold weather, the inevitable spike in COVID deaths as some people seek social solace indoors, the darkness, the political insanity of the post-election chaos, and the mad-dash lame duck. And mostly the sheer isolation my family and millions of others will suffer as our venues for human company become uninhabitable. We thought a heat lamp might buy us a few degrees and weeks, as if there was any chance they wouldn’t be long sold out, just as the country can vainly hope that maybe global warming will overexert itself this winter before taking a rest for the next decade or 10.

The clutter’s still there, less a sign now of activity than of apathy. The neighbors have receded indoors, and the music and meals too, sans company, of course. I can only hope that as we round the corner of winter and this miserable political season, my porch—taunting and reproaching me every time I step out the door—will become a reminder instead that spring (porch dinners! impromptu gatherings! dare one say vaccine?) is just ahead. —Aaron Wiener

If you follow any part of lefty Twitter, you might have gotten the impression unions are reviving as a force to be reckoned with. Digital newsrooms are increasingly unionizing, even as the industry collapses around us, and legacy publications like the New Yorker are finally agreeing to simple demands like not firing workers without just cause. Workers at nonprofits are realizing that they, too, need to have their labor protected. Over the past several years, teachers across the country have risen up under the Red for Ed umbrella, an inspiring bout of activism that isn’t just about fighting for their own rights as employees but also protecting their students. NBA players staged a wildcat strike to protest police violence.

I love reading a good labor success story, and not just because they generally have a strong narrative arc. I’ve been co-chair of Mother Jones’ union for the past three years, and despite all the articles I’ve written or edited—and am biased to think all have been brilliant—winning a strong collective bargaining agreement for my colleagues is probably my proudest achievement since I started working here seven years ago. Everyone should unionize (I’m talking to you, middle managers) and then get feisty with their bosses!

But looking beyond the unionizing surge in some areas…that’s not what’s happening broadly in the country. There are now 27 states with so-called right-to-work laws that make it harder for unions to recruit and function, with five states, predominantly in the old industrial Midwest, adopting such laws over the past decade. As Josh Eidelson reported for Businessweek this summer, companies spend millions annually on anti-union “labor relation consultants” to tamp down union drives. “Each step forward [for labor],” he writes, “depends on a certain amount of luck and is vulnerable to being banned by hostile courts and politicians.”

Last year, just 10.3 percent of workers across the country belonged to a union, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, a record low since the agency started tracking that stat in the ’80s, and the lowest rate since WWII. Though only a slight drop from the year before, the reality is that despite the resurgence of union activity, there’s been a trend of a steady decline over the past several decades.

What’s even more troubling is the fact that there’s a split in the types of workers who belong to unions. Among public sector employees, the unionization rate is 33.6 percent. But for private employers, it’s a piddling 6.2 percent. And thanks to the Supreme Court’s 2018 Janus ruling, public sector unions can’t require “fair share” dues, even while they’re bargaining on behalf of workers. So far that hasn’t been as devastating as some feared at the time, but that initial ruling could have been just an opening salvo. As In These Times reported this summer, the same plaintiff, Mark Janus, is back before the court, petitioning that in light of the 2018 ruling, the union should be forced to refund previously collected dues.

The court’s conservative majority was already predisposed to be anti-union, even before the confirmation of Amy Coney Barrett, and as Jacobin noted, her track record in lower court cases is that “corporate interests prevail over workers.” With a 6–3 conservative split on the court, it’s only a matter of time before the appearance of new legal attacks on organized labor, potentially trying to expand right-to-work to the entire country.

A President Joe Biden could try to stem this worrisome trend. He’s got an extensive plan for various ways to make organizing easier for current unions, while penalizing companies that try to punish workers trying to form unions, along with a call for card check and simpler elections. The former vice president also intends to push for a federal law to repeal the state-level right-to-work restrictions, all of which would vastly improve the landscape. Many of these plans are contained in the Protecting the Right to Organize Act that the House passed earlier this year. Timing, as we know, is everything, and that measure passed shortly before the pandemic shut down the economy (not that the bill would ever have arrived at President Trump’s desk for his signature).

Biden’s agenda would become law at the same time that, thanks to failures of the current Republican Senate to pass a COVID stimulus package, the economy will be in a dire state with millions unemployed. So far, it’s unclear how job losses have been distributed between union and non-union workers. With heavily unionized workforces like the airline industry furloughing and laying off workers, the numbers from the Department of Labor next year won’t be pretty. Plus, the lack of federal aid means state and local government budgets might have to be slashed drastically, potentially cutting into those heavily unionized workforces.

Still, anxious as I am, I keep trying to reassure myself with the fact that maybe lefty Twitter is onto something. Maybe the spirit of these smaller union organizing drives could lead to a broader revitalization nationally. As the namesake of our magazine put it, “The first thing is to raise hell. That’s always the first thing to do when you’re faced with an injustice and you feel powerless. That’s what I do in my fight for the working class.” —Patrick Caldwell

On the eve of the presidential election, one the New York Times warns poses the “greatest threat to American democracy” since the Second World War, it comes as a nearly impossible, herculean task to consider what exactly everyday Americans have witnessed over the past four years. There’s the unchecked cruelty. Shameless corruption. Rampant racism and xenophobia. Deadly incompetence.

But there’s also just been some unequivocal “weird shit.” The kind of bonkers, epoch-making shit that four years later, I still find it difficult to characterize with satisfaction. It’s certainly been relentless, alternatingly distressing and hysterical, and, on many occasions, it swallowed entire news cycles. We saw the weird shit take many forms, from bean spon-con to sharpies to many White House gaggles. But taking a beat to reflect on the heaping pile of shit left in the wake of the first and potentially only Trump term, it’s @realDonaldTrump—the uncontrolled spigot of misinformation, bigotry, and dumb—that perhaps more than any other feature of the weird shit haunts me most.

At the outset, we mostly saw things like “covfefe,” an internet obsession over a typo that now, after an endless supply of infinitely worse material, hits tragically naive. Our nascent relationship with Trump tweets was reflected in all the ink spilled over whether to take the garbage seriously, particularly from old media guards who believed it beneath them to cover such filth. But that thinking utterly backfired as Trump’s grab bag of dystopia became official government policy, White House announcements, windows into a hateful, insecure mind. Recommendations to ignore the tweets had applied the same misguided notion that turning a blind eye to racist dog-whistles will somehow make the racism disappear.

As a writer whose paycheck relies on staying close to the news of the moment, Trump tweets have been something of an unlikely assignment editor for these cursed times. Four years on, I can say that I feel mostly OK with how I approached this strange and unfortunate task. (Someone’s gotta pick up the shit, right?) But so many have botched the assignment, and continue to do so. Those standing at the false altar of objectivity and centrism still breathlessly repeat untrue tweets verbatim and still decline to label outright lies and racism as just that. When it comes to the weirdest of the weird shit, some still try to treat it as something entirely different, hoping to wring presidential behavior out of, well, weird shit. This unimpeachable failure has been exacerbated by repetition, and it’s left me bone-tired.

It’s a small thing against the cascade of horrors we’ve seen from this White House, but for the sake of democracy and my brain, I look forward to the day that @realDonaldTrump ends. I’m also incredibly anxious that it never will. Once upon a time, I had ambition as a writer. Today, I’m burnt out, with a steaming pile of weird shit to show for it. —Inae Oh

Furious

An edited transcript of a Slack conversation between me and my editor about the Lincoln Project, the Never Trump–led organization that has managed to emerge as Resistance icons—despite the fact that the tireless work of all their now proud, ever-so-concerned-never-Trumpers led to the mess we are in.

Me: I can’t tell you how many times in the last few months I’ve yelled, “Oh, now I’M the asshole.”

My editor: LOL, that would be a great Lincoln Project ad

Me: Except, I hate them.

My editor: Fair, but why do you hate them? Because they made such a fucking mess of the world and are now backing off?

Me: Yes. They’re essentially Victor Frankenstein in the crowd with a pitchfork. Every thing they did to the Republican Party led to this moment.

My editor: Yeah…totally right.

Me: And now they get to be all, “Oooh, my precious country!” Like, fuck off, you built it this way!

My editor: This could be a great post. NOT that I will ever force you to do one.

Me: I feel like [redacted] likes them.

My editor: That’s probably true, but you do have some strong facts on your side.

Me: Republicans really need to leave Abraham Lincoln alone. He’s dead, let that man rest.

My editor: When I looked at Steve Schmidt on 60 Minutes, Schmidt who was responsible for pushing Sarah Palin onto the Republican ticket in 2008, thereby legitimizing the crazies in the party, I wanted to say, “You are to blame!”

Me: Watching MSNBC with him and Nicole Wallace being all “Oooh, those Republicans are so pesky!” Gee, whose fault is that?

My editor: LOL, love “pesky.” Yes, we do know know whose fault it is. But to really find out we can look forward to the Lincoln Project’s collective mea culpa book tour.

Me: “Here’s my book on how I was cancelled, I am also a contributing talking head on CNN!” Like damn, CANCEL ME INSTEAD. 😩

My editor: Yeah, 100 percent. Everyone loves the reformed sinner, I suppose. But they seem to have amnesia.

Me: They’re not so much reformed as just pretending it never happened. I mean Rick Wilson was tweeting racist things in 2015. Now he’s a resistance hero? Forgiveness works in mysterious ways.

My editor: Well, so does repentance.

Me: Makes me wish cancel culture was real. —Nathalie Baptiste

In the nearly eight months since the pandemic shut down life as we knew it, it’s been rare to find glimmers of hope in the media, so I was excited when a magazine I subscribe to included an anecdote in its lead that promised to be “an act of hope—that life would soon resume.”

That act, it turns out, was the purchase of a $28,000 pair of diamond earrings auctioned off by Sotheby’s.

While I wouldn’t call it hope—I would not be enjoying said diamonds—I was somehow, weirdly, possibly comforted by the fact that as everything else is in upheaval this year, Town & Country still runs stories headlined “Bangles in a PANDEMIC? The shelter at home shopping network is here, and it’s all about jewels—lots of them.”

The magazine has basically been my favorite hate read since a Fourth of July weekend away with friends last year, back when sharing a space with people outside your family was an act we all took for granted. As I lazily flipped through my host’s magazine rack, not expecting much, I became instantly sucked into the collection of Town & Country issues, transported to a weird alternative timeline where all of the day’s biggest news and scandals were reframed to focus on the true victims: the unfairly demonized rich. The magazine’s story framing was truly flabbergasting:

- The opioid epidemic? Story headline: “Hello, My Name Is Sackler: When your husband and his family are accused of making billions off the opioid crisis, do you get to be a rebel without a cause?”

- The college bribery scandal? Headlined “Is Your Money Still Good Here: The pay-for-play college scandal threatens to end a time honored system of favor trading.”

- GoFundMe? “Suddenly, scanning your social media feed can feel like a walk down BEGGAR’S LANE [sic]. Can you escape with your wallet and relationships intact?”

- #MeToo? Header cartoon of Les Moonves, Michael Cohen, and Charlie Rose at a steakhouse alongside this headline: “How to navigate eating out—and fellow diners—post disgrace.”

I rushed to buy a subscription.

In the December gift guide I was advised to style myself after Kendall Roy, and I read a glossy spread about a Hearst heir getting married at the family castle. The February issue’s jewelry awards opened with a pair of necklaces, one priced $461,000 and another at $824,00, while elsewhere in the issue there was a taxonomy of the types of safari goers: the dowager countess, the honeymooners, the “mommy are we rich?” set.

While it was new to me, the absurd elitism of Town and Country certainly wasn’t new. It’s one of the longest-running magazines in the country. When a new editor took over in 2011, the New York Times called it “an institution that has been edited, since its founding in 1846, for an affluent, ambitious reader eager to master the art of living well.” Stellene Volandes, the magazine’s editor-in-chief since 2016, has been described on the website as a “known jewelry expert” who “speaks frequently on the topics of luxury and jewelry.” How T&C covers these travails of the rich isn’t trivial: Its print circulation of 425,000 is more than twice ours here at Mother Jones. Movie stars grace its cover. Michael Bloomberg and Chelsea Clinton both spoke at its first “philanthropy summit” back in 2014. Serious, good journalists whose work I enjoy elsewhere, like Taffy Brodesser-Akner and Adam Gopnik, contribute to the magazine. (I have to imagine their per-word rate is great, and so hopefully the executives at Hearst ignore this article when I someday pitch them.) Much of each issue doesn’t read all that different than any other glossy magazine that peddles a vision of high-class life (GQ’s list of the best leather jackets starts with one costing nearly $7,000), but there are about two to five stories in each issue that stop me cold, awed at the way parts of the world have been reframed to best pamper the cloistered elite.

But from the outset of the pandemic, it was clear that the rich were not handling lockdown well. Nor was the magazine. It was, like the people it covers, mostly operating in an alternate universe (one in which the net worth of billionaires soared while more than 22 million jobs were lost). And what I once found amusing, even charming-yet-cringe-inducing, now felt gross.

One week early in the pandemic, as the rich fled to their luxurious vacation homes, imprisoned the help, and sang off-key covers in misguided attempts to calm the normals, I checked T&C’s website. It took a decent bit of scrolling to find the first COVID reference, which came in a bloc on the homepage for “All the Latest Royal News.” Those stories were mostly about how various members of the royal family—even as distant as Prince George’s godfather—donated to various relief efforts. There was an entry titled “Queen Elizabeth Will Not Have a Gun Salute on Her Birthday for the First Time in Her Reign.” The tragedy.

Like many print publications—us included—T&C’s shipping schedule precluded it from focusing on COVID in the first issue to arrive after lockdown. Instead: a guide to improved face lift procedures, with doctor recommendations in NYC, Chicago, LA, and SF, and a story about how just no one wants to retire anymore, pointing, of course, to exceedingly rich retirees (written by Joel Stein, whose latest book is entitled In Defense of Elitism). The only overt mention of the coronavirus came in the opening Editor’s Letter, wherein Volandes notes the issue was started in their offices and wrapped after everyone had to be sent home. It included a staff list of favorite comforts, mostly surprisingly down-to-earth suggestions of alcohol, sugar, and exercise (and one truly shocking shoutout to Jenny Odell’s excellent anti-capitalism manifesto How to Do Nothing; Erik Maza, I see you there as a fox inside the henhouse, though your story recommending a $12,9000 watch has me thrown).

Over the coming months, the influence of the pandemic became more overt, if no less unreal. I knew the world was going to shit, but I still took some gawking pleasure in the summer issue, particularly the “Dreambook” of fancy vacations to take once it’s safe to travel again. One page listed “Healing Havens: Because there’s no therapy quite like travel plus treatments.” (Thankfully no mention of pseudo-science ’rona cures.) The issue also included a list of suggested “simple pleasures,” some of which were actually perfectly relatable. (No. 6 “Say Yes to the Martini” spoke to this writer.) But No. 13 was just too priceless (or pricey) a summation of the T&C ethos. In “Grocery Shop As If You’re Going to the Theater,” longtime Vanity Fair writer Amy Fine Collins offered this practical advice: “Because you are: the theater of the street. Getting dressed with care is a mood elevator; it’s a visual, sensual, and aesthetic pleasure. Try hunting for your disinfectant spray the way I do—in vintage Geoffrey Beene and Jen Schlumberger for Tiffany & Co. jewels.”

The annual philanthropy list in that issue was cringe inducing. Alongside worthy names like Anthony Fauci and Jose Andres, there was New Orleans Pelicans owner Gayle Benson, worth more than $3 billion, getting plaudits for…not being a monster? She “guaranteed wages for workers during the closure, as did others, including Dallas Mavericks owner Mark Cuban and Washington Wizards owner Ted Leonsis.” How benevolent of the billionaires to pay their employees. Guess that somehow counts as philanthropy?

Things were in full swing by the September issue—and with that, I was nearing my breaking point. The issue featured the aforementioned pandemic jewelry article and a multi-page spread, titled “The Bunker Boom Market,” featuring some of the most expensive home sales of the year, with Jeff Bezos’ $165 million property in Beverly Hills beating Mike Bloomberg’s $45 million Colorado ranch. “Whether they’re purchasing beachside estates, ranches on thousands of acres out West, or multiple apartments to combine into enormous urban skyscraper compounds, in 2020 the ultrawealthy paid a premium for privacy and, above all, space.”

Accompanying this spread was a sidebar about home upgrades: “Today you’ve got to drag your guests to the control room to show off the latest status symbols, like a Zehnder ventilation unit or the UV light that’s connected to your HVAC.” Leaving aside that no private residence should have a space that could be termed “the control room,” it was yet another sign that the uber-wealthy think they can buy their way out of a public health crisis while the rest of us leave our friends locked out of our houses.

It was just too much. I know I’m surely not the target audience for this—I don’t fit their reader profile of a household income of $197,000 or an average net worth of $2.3 million—but it makes this “journalism” of coddling the sensibilities of the sheltered wealthy too stomach-churning in a year of staggering death tolls, racial injustice, and the worst economic crash since the Great Depression.

I left my October issue untouched for weeks, only diving in when I sat down to write this. In it I found a guide to how one should defend themselves if they were photographed with Jeffrey Epstein co-conspirator Ghislaine Maxwell. “To be sure, if you go out enough in New York, you run a distinct risk of being photographed with someone who later becomes infamous,” the magazine put it. Luckily, none of us are going out to parties anytime soon, and when we do eventually return to normal, if this sort of high-society sentiment is left in the garbage heap of 2020, I won’t feel too sad about it. —Patrick Caldwell

If I drew one of those old-timey phrenology charts of my brain at this moment I’m frightened to think how much space would be occupied by all things Trump. I know I’m not alone; the president owns major real estate in the heads of most Americans right now. It was once a cherished cliché that Americans vote for someone they’d like to have a beer with. Somehow we ended up with a teetotaling rageaholic. I think we also vote for the person we don’t mind (or mind least) as a long-term guest living rent-free in our brains.

Over the five years that Trump’s been surfing on my mental air mattress and peeing on my psychic toilet seat, he’s been more than just a bad guest. He’s more like a dead rat in the walls; an inescapable presence, making me want to flee my own thoughts. Every single morning before I’m fully awake I’m hit with the dull thud of the realization that, damn it, he’s still here—in the White House, and in my brain. I have to tiptoe around my own unconscious to avoid bumping into him.

And the worst part may be that when I do manage to banish him from my thoughts, I feel like I’m only making things worse. Normalcy has come to feel unearned, frivolous. A megalomaniac is ruining people’s lives and trying to torch democracy—how dare I read a comic book or take my kids to the beach?

In a brief moment of what I had thought would be escape, I recently watched an episode of Our Planet that featured Ophiocordyceps, the fungus that “zombifies” tropical carpenter ants. Infected ants are hijacked and forced to climb onto a leaf above their nests, then immobilized while a phallic stalk grows out of their heads to drop spores onto the unsuspecting colony below. The really horrible part is that the fungus doesn’t actually take over the ants’ brains—they’re essentially conscious as their bodies are turned into a biological weapon. My Trump-addled mind couldn’t help but think that like this ancient parasite, the president is perfectly evolved to isolate us, paralyze us, and use us to spread his contagion. All while we’re fully aware that our detachment and solipsism are signs that we’re letting him win.

Having George W. Bush rattling around in my brain wasn’t like this. Sure, I was filled with outrage and disgust and resignation for eight years, but somehow the thought of him didn’t contaminate all my pleasures and private moments. Trump’s soulless, stultifying, ubiquitous presence is something different. As the embodiment of the ugliest side of white America, he is both revolting and familiar. Sending him packing will only be the first step toward freeing my mind. —Dave Gilson

In a recent video for Cameo, the popular app that lets everyday nobodies like you and me hire celebrities to star in short, personalized greetings, our recruited star delivered. “Happy birthday, Tina!” Jim O’Heir, the actor beloved for playing Jerry in NBC’s Parks and Recreation, bellowed into the camera.

“I did hear from the gang,” he continued, name-checking the senders of Tina’s birthday wishes. “I heard from—so I don’t screw it up—Inae, I believe I’m saying that correctly—and Jen, Shannon, and Marc.” O’Heir continued, performing a delightfully absurd ode to Li’l Sebastian and echoing our hopes for 2020 to burn.

It was a minor moment in the six-minute video but as someone who has had her name mercilessly botched—”Ho Eenie,” “Eye-NAH,” “In-UH”—since childhood, the memory of substitute teachers still sparking some panic as I flashback to dreaded morning roll calls, O’Heir’s concerted effort to properly pronounce it came as a relief. It was an oddly intimate, albeit small, joy attached to a profoundly silly gift. “He didn’t absolutely butcher your name,” a friend noted in a private Instagram comment, one of several people to similarly notice. “Super impressed.”

So, when Republican Sen. David Perdue started intentionally mucking up Kamala Harris’ name, to say that I was less than “super impressed” is putting it mildly. “KAH-mah-lah? Kah-MAH-lah? Kamala-mala-mala?” the Georgia senator asked supporters at a Trump rally. “I don’t know, whatever.” The crowd roared.

For most people watching from afar, the overt racism animating Perdue’s performance was difficult to ignore. While mispronouncing non-white names is often indeed an innocent, unintentional mistake, one typically amended upon the first clarification, Harris is a historic vice presidential nominee and former presidential candidate. Perdue is her colleague in the Senate, where she reigns as one of the most prominent women in American politics. He, meanwhile, is something of a GOP backbencher from Georgia now locked in a tight reelection fight against a 33-year-old, never-before-elected Democratic challenger, Jon Ossoff. To feign ignorance to Harris’ name with a breezy, “I don’t know, whatever,” after Donald Trump and others in the GOP resurrected untrue, birther conspiracy-style attacks to question her eligibility, is simply unbelievable—though the cheers responding to Perdue’s remarks show that they had landed precisely as intended. (Plus, while not the most important detail here, Perdue wasn’t even being particularly original; his peers, including the president himself, have repeatedly screwed up Harris’ name as red meat for the base.)

Perdue’s office has since denied the charges of racism, claiming, unconvincingly, that “he didn’t mean anything by it.”

But even if you do acknowledge the racism seething in Perdue’s mockery, it’s still easy for some to couch it as a small offense against the cascade of unrelenting bigotry flowing from the current White House. That caveat may be warranted, but don’t be fooled: That doesn’t make Perdue’s salvo of “KAH-mah-lah” any less repugnant. Mere seconds into watching Perdue, I recalled the resentment I once held toward my immigrant parents, who, from the perspective of a first-generation teenager growing up in an overwhelmingly white community in New Jersey, had burdened me with the strange, inconvenient stumble of letters that spelled out “Inae.” When the mispronunciations arrived intentionally—as they did countless times by neighborhood dummies and parents of school friends—the hate was instantly recognizable. “You can call me whatever,” is what I’d reflexively offer, hoping to signal that I was at once easy-going and immune to their contempt. Meanwhile, a slow-burning bitterness was building up. Little did I know that I had been green-lighting attempts of erasure.

That desperate willingness to conform faded during college, and I’ve long since embraced what used to make me recoil. The decision to keep my name upon getting married and to decline being rebranded with my partner’s surname, White, was borne more out of a love for my Korean name and family, less out of my feminist leanings. Plus, “Inae White” is wholly ridiculous. As an adult, I no longer experience the anxiety of introductions. But antics like Perdue’s still strike a deeply familiar chord. That makes it all the more lovely when strangers like O’Heir go the short but meaningful distance to get it right. Come November, perhaps we’ll be hearing less “Perdue” and more “Ossoff” in the world. Give it a few more years, and maybe non-white names will overtake the Davids.—Inae Oh

Fox’s The Masked Singer is the greatest, most deranged acid trip of a show on television the past few years. An adaptation of a South Korean series, it premiered in January 2019 and is perfect for the surreal times of the Trump era. A panel of awful judges (Jenny McCarthy and Robin Thicke? Really?) try to guess the identity of usually c- or d-list celebrities in elaborate, dystopian outfits so ornate that the show dethroned RuPaul’s Drag Race this year to win the Emmy for reality TV costumes. The first season featured Terry Bradshaw in a serial killer-esque deer costume, and Joey Fatone went method in a creepy Donnie Darko-styled rabbit costume. The finale ended with T-Pain winning the contest by showing he had an amazing voice and didn’t need auto-tune (though an adorable monster costume helped). Then, in season 2, Wayne Brady’s performance as steampunk fox was a thing of true beauty.

So I was excited when I saw it was among the early batch of TV shows beginning to come back after COVID shut down Hollywood production. And it seemed like a natural for the social distance era, since they’ve made great hay about the elaborate security lengths taken to keep the identities of the contestants secret. And when host Nick Cannon came onstage for the first episode that aired in late September, he opened with a knowing joke. “Finally we have something fun involving masks,” he said as a CGI T-Rex roared behind him.

But then the show started…and there was a full studio audience of unmasked people dancing along to the music and cheering wildly. What the hell? It looked like the most COVID-unsafe setting imaginable. After some frantic googling, I realized it was all a ruse, with past footage and sleight-of-hand digital editing superimposing past crowd footage onto a mostly empty set. But this is hardly obvious. Unless you did online research, you’d only know it by reading the small-font, fast-scrolling credits which state, “Due to health restrictions, visuals of audience featured in this episode included virtual shots as well as shots from past seasons.” (I only was able to read the full thing by pausing Hulu.)

“It feels that through virtual reality and composite and reaction shots, we managed to create the feeling that there were people in the room,” a Fox exec told Deadline.

But this is horribly, horribly irresponsible. Yes, TV shows can serve as a brief respite from the panic and overwhelming dread of our current moment. But we’re still living amidst a dangerous pandemic, currently entering its third peak, that has killed over 230,000 Americans at the time of this writing. Fatigue at restrictions has set in, and too much of the country is trying to act as if things are back to normal. TV doesn’t need to foster that.

What’s especially frustrating is that in all other matters, the show is exceeeeedingly contrived in a knowing way. Last season, Lil Wayne was the first contestant sent home, while somehow Rob Gronkowski’s rapping propelled him on for several more episodes. During the current run, Busta Rhymes was likewise the first ejected even though the Dragon slayed a cover of LL Cool J’s “Mama Said Knock You Out.” Clearly it’s a show rigged to allow the famous celebrities to come on for just one episode, even if they’re more talented than their peers, and the show does little to hide this phenomenon. (In the second episode this year, Mickey Rourke didn’t even want to play along with the ruse and immediately demasked himself after his performance.) The amount of winking at the camera is part of its charm. The show could have easily come up with some trick to keep the silly magic (a CGIed audience of judge Ken Jeong filling the stands?) without alienating viewers.

Instead, Fox hopes it can trick viewers and pretend life is just fine. It only makes me dread what Jenny McCarthy might say if there’s a vaccine available by the time they film the next season.—Patrick Caldwell

This is not the year for watered-down, flimsy-ass feminism. Women’s rights to bodily autonomy hang precariously in the balance; Black women are still three times more likely to die in childbirth in this country than white women; Latina and Hispanic women who flee to the United States seeking safety with their children are finding themselves criminalized and separated from them; all of us still get paid less than men (and women of color get paid less than white women). My point is, if your feminism isn’t inclusive and intersectional and nuanced and tough, maybe you should consider moving to an island where you and Peggy Noonan can be happy together saying things like, “It’s not racist to point out that she comes across unprofessional…,” about women like barrier-breaking vice presidential nominee Kamala Harris.

I get real worked up when some conservatism appears in my feed masquerading as women’s empowerment. I’ve been having some pretty weird (and realistic!) pandemic dreams lately, and when I came across a voting PSA featuring Republican Sen. Marsha Blackburn from Tennessee, my home state, recorded for the Skimm, a newsletter which happens to specialize in watered-down, flimsy-ass feminism, it seemed a little too on brand. If I had to read the Skimm regularly, my eyeballs would be permanently fixed toward the back of my skull from rolling them so hard. The language is cutesy at best, infantilizing at worst, and its approach immediately brings to mind words like “empow-HER-ment” and “SHE-E-O,” punny approaches to addressing inequality through language that could never fix anything, but gosh aren’t they adorable!

It’s not so much that Blackburn exhibits this sort of silliness—she does not at all, actually—but she was Trumpian before Donald Trump ever thought about running for the presidency, and when he was elected, she fell in line so fast it’s a wonder she didn’t accidentally launch herself into the sun with all that momentum. She is, however, a master at wrapping herself in the sheerest cloak of white feminism possible. Over the years, she has led attacks on Planned Parenthood and abortion rights broadly, all in the name, of course, of protecting us women. She has voted against equal pay protections for women several times, claiming, “women don’t want it.” She co-sponsored the wildly unscientific Born-Alive Abortion Survivors Protection Act. But yeah, Amy Coney Barrett’s confirmation to the Supreme Court was a big victory for women! Sure.

So when I see Blackburn encouraging people to vote on the Skimm—and when I see the Skimm, which reaches some 7 million inboxes each day, giving her such a big damn platform—you’ll forgive me if I meet it with some skepticism. Because all I can hear is a woman who has benefitted from wealth and white privilege encouraging others like her to vote in their best interests, not in the best interests of the disempowered and disenfranchised in this country. I guess it makes sense for the Skimm, which specializes in taking deep social and political issues and simply skimming the top off of them, discarding the substance. —Becca Andrews

I know I’m late to the Marie Kondo organizing craze. I held out as long as I could. But I recently moved, and moving required dealing with piles of junk I never knew I had. In the middle of trying to find new homes or space in the trash for the things I no longer needed, I saw a friend’s Instagram post about her new obsession, The Home Edit, a Netflix show featuring two women overly enthusiastic about organizing things in the order that makes the most sense to them, by the colors of the rainbow.

A day later, I saw that same friend post a picture of her shopping cart from a store. It was filled with dozens of acrylic boxes to organize her shoes, tagging The Home Edit. She seemed proud to take back some control in a chaotic time, even if it was just her closet. But I went somewhere else: a flash to a few years from now, when all that plastic would end up in a landfill, or worse, burned by an incinerator in a poor community that is already suffering from toxic pollution.

I knew I wasn’t going to like this show, but I couldn’t help myself and tuned in to hate-watch it anyway. The first episode features a very sunny Reese Witherspoon wishing to organize her old Legally Blonde costumes, feeling very out of step with the times. A few minutes in, the two stars, Clea Shearer and Joanna Teplin, who’ve already plugged their product line and Instagram, say, “The rainbow really represents what our company stands for. It’s a smart functional system, it’s orderly and it’s really beautiful to look at. Form plus function.”

One alarm bell is that the stars are trying to sell the viewer something. Like Kondo, they have their own product line, so for their purposes no one can do too much streamlining. Streamlining has to also mean buying more crap, and in The Home Edit case, it’s single-purpose acrylic items to make your closet prettier. Shearer and Teplin have an aesthetic, and that aesthetic is plastic. For Witherspoon and other celebrity clients, they use things I didn’t know existed, from specialized acrylic purse hangers to shoe platforms to boot shapers.

In a year where there’s too many things to be furious over, getting angry over this needless waste, misbranded as tidying, may feel like an inconsequential distraction. But I couldn’t get it out of my head how even tidying up and minimalism have been co-opted by rampant consumerism. The implicit message to viewers is aspirational about capitalism: You can have a better life if you just buy the right things and don’t think too deeply about the cost that imposes to other people and to the environment.

Instead of thinking of the present only when we buy, I wish more people would consider whether they’ll need something in four years, or if those purchases will end up being a ridiculous waste of space and money. And when you’re filling loads of garbage bags with junk you no longer have a use for, I want people to confront why they ever felt the need to buy it in the first place, and the cost that imposed on the planet. Is a rainbow-colored closet filled with plastic really worth it? —Rebecca Leber

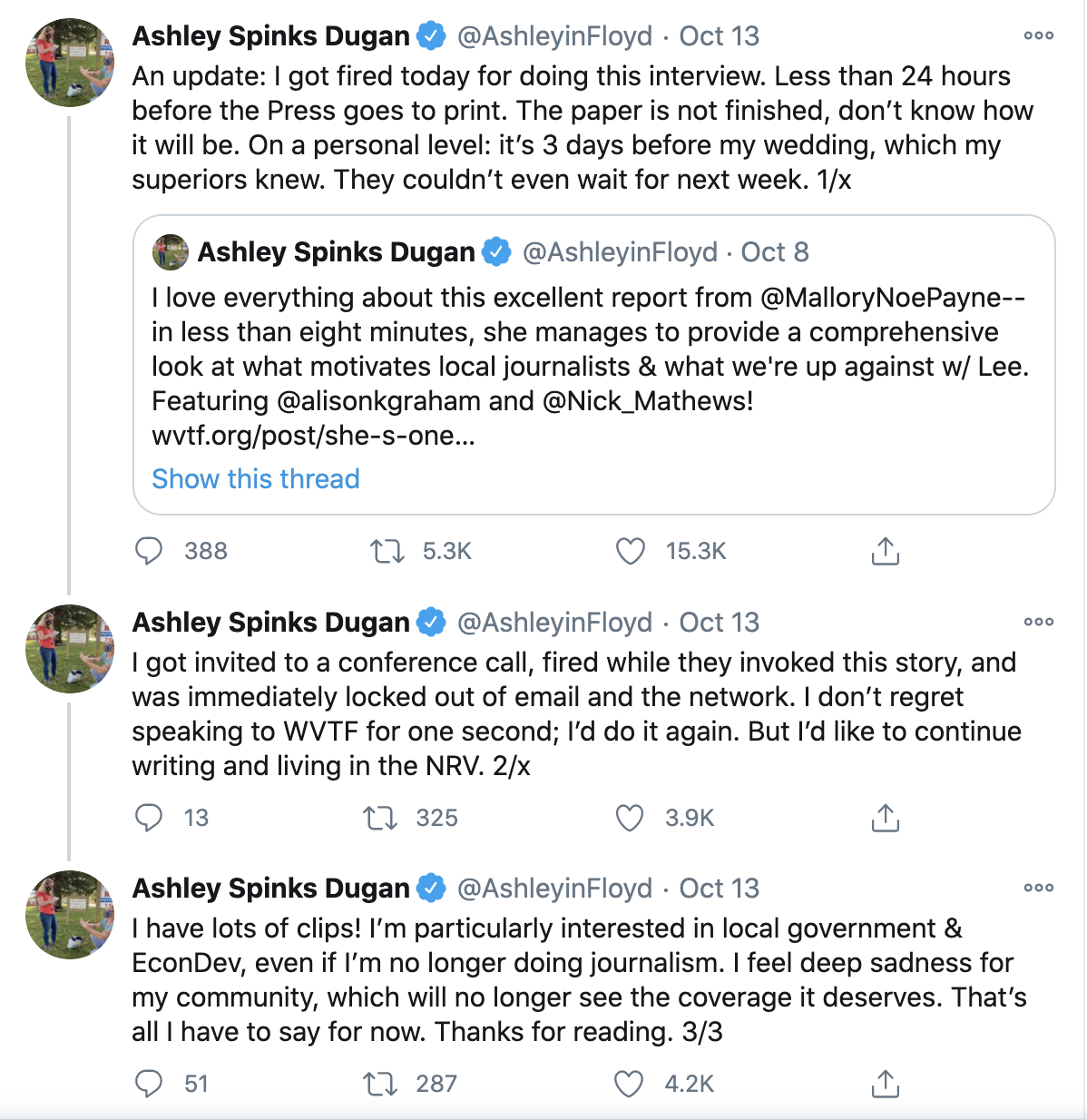

I’m angry about this firing:

Ashley Spinks is a journalist in Virginia who was responsible for putting together her town’s weekly newspaper, the Floyd Press, all by herself—because all the other reporters and editors were previously laid off. She was essentially a one-woman newsroom. Then in October, her employer, Lee Enterprises, one of the largest corporate newspaper chains in the country, fired her too—because she spoke with another publication about how hard her job was. And they did it three days before her wedding, which she says her bosses knew about. In a time when local newspapers are suffering financial peril—not to mention repeated verbal bashing from President Trump and actual physical danger—a media company firing a paper’s last standing reporter for speaking with another reporter feels like a blow too far. —Samantha Michaels

There have been a lot of strange headlines over the past half year, but a Pitchfork article in August about a Brooklyn press conference featuring Chuck Schumer and LCD Soundsystem leader James Murphy is still probably the story I had least expected to read. Schumer, the longtime booster of New York’s finance industry and a hood ornament for the cleaned-up era of the city, seemed like just the sort of Bloomberg-like politician whom Murphy had bemoaned in “New York I Love You, But You’re Bringing Me Down.” But the oddball combo had teamed up for a good cause, Save Our Stages, a call to devote funds to concert venues that had been shut down thanks to COVID.

For the past seven years I’ve lived in a sometimes too crowded old group house, suffering through molding plaster and a rotating cast of roommates (some dear friends, others morally decrepit Craigslist strangers). Beyond my landlord not recognizing that he could be charging far higher rent, one of its key selling points is that it’s less than a mile walk from five of the best music venues in the nation’s capital, ranging from the cramped, 250-person capacity second floor stage of DC9 to the storied 9:30 Club. But of the bunch, U Street Music Hall has always held a special place in the dark, sweaty basement of my heart, and in early October it announced that it was closing permanently, at a time when it was also supposed to be celebrating its tenth anniversary in the city. “The reality is there aren’t going to be any shows for six months to a year, especially in a basement dance club,” the owner told the Washington Post. “That’s just not conducive to today’s environment.”

Before the pandemic, I’d usually go to a few concerts a month. My friend group’s email chain titled “Winter/Spring Concerts” is up to 162 messages since it started on January 2, with a whole calendar of shows mapped out through the summer before the thread turned to lamenting cancellations, and then venue closures. U Street Music Hall was always a regular for me. It had shit but cheap beer; the bathroom lines were often too long thanks to a lack of stalls and too many people trying to find a discreet spot to take Molly or other substances; unless you were at the front of the stage during a sold-out show, you might’ve spent the night watching a support beam. But it had the best sound system in the city, an eclectic mix of genres booked, and was the best spot in the city to dance until late at night while DJs spun. It was the sort of place where I got to watch a short, intimate set from Robyn after she had opened for Coldplay at the NBA arena earlier in the night, or catch Charli XCX for one of her first stops in the US, and a home to local bands taking the step up from house shows.

Congress’ inability (mostly thanks to Mitch McConnell’s intransigence) to pass extra stimulus is galling for a whole host of reasons, as unemployment soared beyond anything faced during the Great Recession a decade ago. They passed widespread business support, but unless you’re a favorite like airlines, the businesses that are particularly harmed by the pandemic have been left to fend for themselves with no targeted relief. The stories of endless lines at food pantries and the coming wave of evictions are truly horrifying. And while restaurants and other businesses that closed during the early lockdown days slowly reopen, it’s hard to imagine a world where concert clubs reopen until there’s a vaccine. The bartenders, bouncers, sound and light engineers, and touring musicians who rely on that for their income are being left behind. And a core part of the fabric that makes cities vibrant and artistic will disappear along the way.

By happenstance, one of the last shows I went to before the pandemic shut everything down was a late January James Murphy DJ set at U St Music Hall. It was a crazy night, I was still jet-lagged from a west coast red-eye flight back that morning, but friends stayed out dancing until we were all exhausted messes at 3 a.m. I can’t wait until I can once again stay out all night in sweaty, close dancing quarters with all of my friends, and dear lord I hope at least a few of these concert venues are still alive when the pandemic is over. —Patrick Caldwell

There are few things in life I sincerely, deeply love. One of them is science. I love that it’s methodical. I love that it doesn’t purport to be perfect but rather a slow advancement toward truth. And I love that in science, unlike in many fields, a wrong idea isn’t necessarily a bad thing.

At least in the United States, people overwhelmingly trust scientists to act in the public’s best interest. That’s less true of business leaders or journalists or, least of all, elected officials. Trust in science is therefore a sharp tool in responding to public health crises like a pandemic. But over the past several months, once again, we’ve watched bad actors rapidly try to grind down that trust. And I’m tired of it.

The politicization of science isn’t exactly new. See: climate change, vaccines, evolution, the AIDS crisis, the CDC, conservation, heliocentrism, nutrition, wildfires, stem cells. But now, while we’re in the middle of a pandemic with more than 9 million cases in this country alone, politicizing scientific uncertainty has become incredibly, horrifyingly, dangerously easy.

In a 2015 paper, a pair of researchers from Georgia State and Northwestern Universities defined the politicization of science as emphasizing “the inherent uncertainty of science to cast doubt on the existence of scientific consensus.” Consensus, however, takes time to build, and in the case of a never-before-seen virus, when consensuses are still coming into focus, the door is basically wide open to what Merchants of Doubt authors Erik M. Conway and Naomi Oreskes dubbed “doubt-mongering.”

Republicans, mostly, have taken advantage of COVID uncertainty. “To date, most criticisms of COVID-19 models and science, more broadly, have emanated from the political right,” Cornell professors Sarah Kreps and Douglas Kriner write in a September study published in Science Advances on public trust and politicization in science. Statistical models, they write, have become a “flashpoint for debate” during the pandemic. In just one example, Fox News’ Tucker Carlson declared in an April segment about coronavirus case estimates, “At this point, we should not be surprised that the model got it wrong,” adding that an early model from the same institute “turned out to be completely disconnected from reality.” In another example, this one from May, a reporter asked Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis about a projection, and he said, “Has that been accurate so far? Have any of the models been accurate so far?” And during a Senate hearing the same month, Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.) blasted scientists for making “wrong prediction, after wrong prediction, after wrong prediction.”

This is beyond maddening. If you’ve ever asked a statistician about models (and who hasn’t?), you’ve probably heard the popular aphorism, “All models are wrong, but some are useful.” As one public health expert told me in July, models can help us understand the dynamics of a given process but aren’t observations of real events. “No model will accurately reflect reality,” he said. In essence, models aren’t perfect and no scientist expects them to be. Unfortunately, it appears no one shared this sentiment with Carlson or DeSantis or Paul.

Then there’s the president himself. I could devote an entire book to the anti-science rhetoric of Donald Trump, and it’s far from limited to statistical models, so I won’t go deeper here, but be sure to check out the extensive timeline my colleagues built chronicling his coronavirus denials.

While Republicans may be the primary perpetrators of scientific politicization, Democrats are not completely off the hook. Comments that seek to cast doubt on the scientific process—especially coming from Democrats—make a difference in public attitudes toward science. In their Science Advances study, for example, Kreps and Kriner, in a series of five experiments, presented statements about modeling data to more than 6,000 Americans. They found that when criticism came from Republicans, it had little impact on people’s trust in science, regardless of their party. But when criticism came from Democrats, it reduced the respondents’ trust in science.

Kreps and Kriner also tested a real-world example: When people read criticism from New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo (“They come up with all these projections, we’re going to do this in May, we’re going to do this in June, we’re going to do this in July. They have no idea.”), it eroded their support for relying on models and support for science generally. But participants’ attitudes were not affected when they read criticism from Sen. John Cornyn (R-Texas), who tweeted in April: “After #COVID-19 crisis passes, could we have a good faith discussion about the uses and abuses of ‘modeling’ to predict the future? Everything from public health, to economic … predictions. It isn’t the scientific method, folks.”

The Cuomo Effect is essentially a warning: “It suggests that the onus is on Democrats to be particularly careful with how they communicate about COVID-19 science,” Kriner said in a September press release. “Because of popular expectations about the alignments of the parties on science more broadly and on issues like COVID-19 and climate change, they can inadvertently erode confidence in science even when that isn’t their intent.”

In the science world, uncertainty isn’t a dirty word—in fact, the ability to say “we don’t know” is arguably one of science’s greatest strengths—but at a time when everyone is demanding answers, uncertainty is being used by political figures for their own benefit, and, possibly, at the expense of public trust in science. That’s not only irresponsible; during a pandemic, it’s deadly.

So, for the love of science, let’s leave the scientific debates to the experts. —Jackie Flynn Mogensen

The way prosecutors have handled Breonna Taylor’s death deserves a top spot on the list of rage-inducers. None of the police officers are facing charges for killing her. Sure, one officer was indicted for firing his gun into a neighboring home, damaging some walls. But isn’t that more insulting? The fact that our use-of-force laws make it easier to punish cops for property damage than for murder is one of this country’s biggest failures. As my colleague Nathalie Baptiste so sharply put it, “It seems as if due process and the presumption of innocence can be flexible concepts, deployed for the convenience of law enforcement. For others, especially Black people, that right is often stripped away.”

Let’s also talk about how shady the lead prosecutor, Kentucky Attorney General Daniel Cameron, has been on this case. In a press briefing, he insisted that officers knocked and announced themselves before barging into Taylor’s home in the middle of the night. But he failed to mention that about a dozen witnesses said they didn’t hear knocking or an announcement. Only one witness claimed to hear the police announce themselves—and that witness initially told investigators he hadn’t heard anything.

What’s more galling, though, is what we’re still learning about how Cameron conducted himself. He says he presented all the evidence to the grand jury that decided whether to indict the officers. But in late October, an anonymous juror released a startling statement alleging that Cameron never gave them the option to pursue murder charges. “The grand jury did not have homicide offenses explained to them,” the juror wrote. “The grand jury never heard anything about those laws.” Cameron says he presented all the facts, but it seems like the police’s side of the story was the side he cared about most. That’s not justice, and certainly not the kind of justice Breonna Taylor deserved. —Samantha Michaels

Tall people make more money. A 2004 study showed that every inch of height adds $789 to a person’s annual salary. That means that someone who is 6 feet tall makes about $5,523 more a year than someone who is 5 feet, 5 inches, like me. Another study found that people over 6 feet earn $166,000 more over the course of their careers than people who are 5-foot-5.

I’ve been thinking a lot about these studies recently and not because of my relative height disadvantage. Every time I see Donald Trump (6-foot-3) use juvenile tactics to try to intimidate his opponents. Every time I see that three-fourths of the House and the Senate are men. Every time I see a political party engaging in brazen power politics, like stalling one Supreme Court nomination (of a short man) while turbo-charging the confirmation process of another. Every time I see this arbitrary yet relentless assertion of height power, I can feel myself getting furious.

Donald Trump’s son Barron recently had the coronavirus, which has swept through Trump’s inner circle with the speed of, well, a highly contagious virus. What did Trump have to say about his son getting a disease that has killed more than 225,000 Americans? That he recovered? That he is doing well? That his father was sorry that he infected him? (Okay, just kidding.) No, for Trump, Barron getting the virus was an opportunity to assert one important fact: His son is tall. At an October 15 rally in North Carolina, here’s what Trump had to say about his son getting the coronavirus:

Trump on his son getting the coronavirus: "My Barron. My tall Barron. He's very tall. My beautiful Barron. Handsome. He is handsome. But my beautiful Barron had it. He recovered, like, so fast. I said, wait a minute: how long did that take?"

— Daniel Dale (@ddale8) October 15, 2020

Trump’s bizarre response, both mawkish and flippant, is telling. His obsession with youth, beauty, and height are all part of his swaggering, machismo brand and yet another assertion of his “very good genes.” This is the putative leader of the free world for goodness sake. And then, to add insult to injury, there is the quantifiable fact that tall people make more. Damn. Money.

Clearly, being tall should not correlate to a higher salary. The richest and most powerful people on the planet spend their days sitting behind screens and talking on phones. Maybe they get driven around to some meetings. Barring professional athletes, powerful people have gotten where they are in the 21st century because they are (supposedly) using their brains. I personally have never seen or heard about a wrestling match breaking out during a board meeting.

And yet, the financial rewards tall people enjoy are insane/ridiculous/disproportionate to, well, anything.

It’s embarrassingly base and crudely logical: Height doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It’s an important metric for a reason. Tall people are more likely to be male, to have deep voices, and to be physically intimidating. (Side note: People with deep voices also make more money.)

It’s been 161 years since California Supreme Court ex-Chief Justice David S. Terry, who was pro-slavery, wrote a letter to California Sen. David C. Broderick, an abolitionist, challenging the senator to a duel. Unfortunately, the abolitionist was shot and killed. That was 1859. It is the last notable duel between US politicians before the barbaric tradition became illegal, marking the end of this kind of explicit use of violence to settle political disputes (except, you know, war, and the kind of intimidation we are seeing now, thanks to our president). But the power to physically subjugate someone still yields economic advantages.

It makes no sense. But it also seems to make brutal sense.

I was a ’90s kid, growing up in the electric shadow of the internet. Francis Fukuyama was predicting the end of history. Technology was going to solve the world’s resource shortages. I naively believed that the world was getting better—more tolerant, more fair, more resources to go around. Behind the emancipatory glow of the computer screen, age, gender, race, height, weight, and beauty weren’t supposed to matter. (Yeah, right.) As soon as bandwidth got good enough to transfer images and video, and Facebook instituted a regime of identity, the egalitarian promise of the internet went all to shit.

Now I’m convinced that the internet is ruining my life and destroying democracy. I see the Instagram aesthetic—bright colors, white teeth, filtered perfection—seeping into everything. The amount of plastic surgery on display at the Republican National Convention was mad creepy. Will a first lady ever have gray hair again? How about the first female president? The next male president? The internet was supposed to help set women free of gender stereotypes. But in the age of the influencer, the fe/male gaze has never been more powerful and looks have never been more profitable. Physical appearances garner likes, sponsorships, and, oh yes, money.

Did I mention that many studies demonstrate that tall people make more money?

Reckoning with the ways physical traits, money, race, gender, and beauty give people advantages in life is infuriating. It’s utterly deterministic, the antithesis of meritocracy. I hate that we live in a world of power politics. But I hate even more that these power politics could be based on such stupid metrics.

As I mentioned, I clock in at 5-foot-5 and, unfortunately, I’ve stopped growing. There’s a lot of things I’d enjoy doing with an extra $166,000. But there’s definitely an upside to my stature. At least every time someone looks at my accomplishments they won’t be thinking, “Maybe it’s just because she’s tall?” —Molly Schwartz

Hopeful

The last cool place I went before everything shut down was Death Valley National Park, which in addition to all the famous parts also includes one non-contiguous, 40-acre parcel within the Ash Meadows National Wildlife Refuge in Nevada. The site is called Devil’s Hole. It is a deep underwater cave system nestled in the crag of a scrubby hill whose name I don’t know offhand but in my opinion should be called Devil’s Hill. The Mansons thought the cave was the entrance to underworld, which is not true, but not so wrong that it requires changing the name. According to the National Park Service, the water in Devil’s Hole is 92-degrees year-round—pretty hot!—and the bottom of the cavern “has never been mapped.” Dun dun dun. Devil’s Hole was protected by the park because it is the only remaining habitat on the planet for a tiny little cyprinodontidae, about the size of a silver dollar, called the Devil’s Hole Pupfish.

Over the years, in the interest of preserving this habitat, we—the government, taxpayers, whatever—have turned the hole into something resembling a mini-Supermax prison. When I visited in February, the perimeter was lined with a tall chain link fence with barbed wire on top. There are security cameras along the perimeter and underwater, motion sensors, and seismic monitoring systems. To see the fish, you walk up the hill, through a door in the fence, and then down a long cage-like enclosure to an overlook of an overlook that offers a partial glimpse of the pool from a considerable height above it. Did I see any pupfish? I’ve convinced myself that I did, but it might have just been shadows. There is something wonderfully dissonant about such a magnificent apparatus for something almost invisible. One thinks of Ian Malcom, passing through Isla Nublar, wondering, ah, if there any dinosaurs on the, ah, dinosaur tour.

Being a Devil’s Hole Pupfish is a precarious thing. Their lives are spent in quarantine; they can never leave their home. In fact, they will never travel more than a few feet. Other species of pupfish live in nearby parts of Ash Meadows, but they are forever distanced. Human-induced changes in the water table threaten the Devil’s Hole habitat, as do cruder forms of interference—like when three drunk men broke into the site in 2016, discharged firearms and vomited, and one of them swam naked in the pool, killing a pupfish. (Not a metaphor for our times, just a thing that happened.) The Devil’s Hole Pupfish population has dropped precipitously over the last few decades, and climate change probably isn’t going to do any favors for one of the most immobile populations on earth.

They lack many of the qualities that might sustain other species in the anthropocene. Pupfish are not good to eat—oh God, do not even get any ideas—and you cannot train them to do tricks. I nearly ruined my rental car to perhaps not even see them. And yet we, and they, persist. At a nearby facility, scientists have built a 100,000-gallon, 22-foot-deep replica of Devil’s Hole in an attempt to build up a sort of backup population of pupfish. The park service doubled down on its security measures after the break-in.

Fences are failures, in many ways—an indictment of people’s propensity to destroy, or in different circumstances, a monument to our fears. But I choose to view this apparatus in a different light. We built a cordon around the rest of the world so that these glorious cave guppies can still live free. It was a weird parting thought these last few months, as humanity frantically scrambled to distance itself from itself. Saving the Pupfish certainly won’t save us. It might not even save them. But in a fucked-up world (I refer you again to the Mansons), we’re trying. I’ll take hope where I can. —Tim Murphy

I am often baffled by the amount of time I have spent staring at Donald Trump’s face.

As a graphic designer, Photoshop is both my playmate and my business partner. When I worked in the ad world, my days often consisted of stitching together compiled stock images into scenes—elaborate storyboards made to convince consumers to try the newest lunchtime snack or platinum-level credit card. And while I found the premise of most ads to be tiresome, the variety of storylines at least kept things interesting. I was, admittedly, quite naive about what shifting from advertising to news design in the Trump era would entail, but after nearly two years at Mother Jones here is what I know: I severely underestimated the sheer volume of hours I would log navigating every crease, every hair, every pore of Donald J. Trump, pixel by tangerine pixel.