Mother Jones illustration; US Senate; Getty

Before he was a traitor, Jefferson Davis was a senator from Mississippi. From the moment he walked out of the US Capitol to join the Confederacy in January 1861, his mahogany desk in the Senate chamber became a prize to be fought over, both politically and physically. Sen. Simon Cameron of Pennsylvania claimed to have made this prediction as a parting shot to Davis before his defection: “I believe, in the justice of God, that a Negro some day will come and occupy your seat.” In April 1861, Union soldiers who were billeted inside the Senate located Davis’ former desk and tried to slice it apart. As Senate official Issac Bassett later recalled:

…I heard a noise, as if someone was splitting wood. I looked over on the Democratic side of the Chamber and behold! There was a crowd [of] soldiers with their bayonets, cutting one of the desks to pieces. I hollered at the top of my voice, “Stop! What are you doing?” Several answered, “We are cutting that damn traitor’s desk to pieces.” I ran in among them and told them it was not his desk, that it belonged to the government. “You were put here to protect, and not to destroy!”

The desk was repaired and put back on the floor. Sen. Milton Latham, a pro-Southern Democrat from California, unsuccessfully offered to buy it after he took Davis’ chair home. In the years to come, there would be more battles over whom the desk rightfully belonged to, and whether it stood for tradition or treachery. When the dust settled, Davis and his cause were dead, but the desk was still very much his.

Two weeks ago, Reps. Barbara Lee (D-Calif.) and Bennie Thompson (D-Miss.) and Sen. Cory Booker (D-N.J.), introduced bills to remove statues of Davis and 10 0ther men who served in the Confederacy from the Capitol. Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi has also called for the statues to go, as well as portraits of four former speakers who were Confederates. As the effort to scrub tributes to white supremacists from the halls of Congress gains momentum, a closer look at the history of the desk that once belonged to the president of the Confederate States of America is overdue.

The fight for Davis’ Senate desk resumed in 1870, when Mississippi’s legislature named Hiram Rhodes Revels to a serve a one-year term as the state’s first Black senator. (He was also the first African American member of Congress.) Sen. Revels was sworn in only after a two-day debate in which Democratic holdouts questioned his citizenship and credentials to serve. While there was speculation that Revels would be seated at Davis’ former desk, he did not occupy it, having assumed the office once held by Albert G. Brown, who had also resigned in 1861 to join the Confederacy.

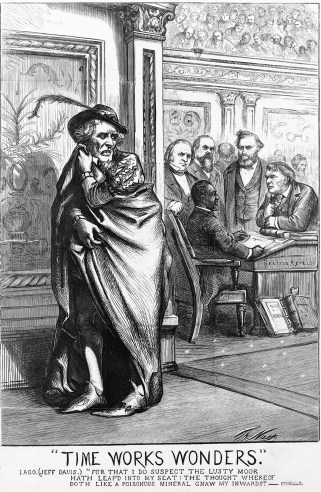

Library of Congress

Yet that didn’t diminish the symbolism of Revels’ ascension to the upper chamber of Congress. Sen. James Nye of Nevada hailed Revels’ arrival as “a magnificent spectacle of retributive justice.” One typically racist account in a Pennsylvania paper griped, “The place once occupied by Jefferson Davis is now filled by the huge form of a Burly African.” Savoring the reversal of Davis’ fortunes, cartoonist Thomas Nast drew him cringing jealously at the sight of the African American senator who “hath leap’d into my seat.”

According to anti-Reconstructionists, the Republicans sought to secure Davis’ old desk for Revels, a notion a New Orleans paper called “a wanton insult, so like vomiting on the grave of a dead grandmother.” But the move was supposedly rebuffed by Edmund G. Ross, the Kansas senator who had been unknowingly seated at the desk. (Ross was already infamous for casting the decisive vote to acquit President Andrew Johnson in his 1868 impeachment trial.) The description of the encounter was suspiciously tidy:

And in order to bring it about [Senators] Sumner, Wilson and half a dozen other negro-worshipers approached Senator Ross, of Kansas, and said to him, “Arise, exchange seats with the man and brother, Revels, that history may tell, to the perpetual confusion of Southern chivalry, that a despised negro occupies the seat of the traitor Jeff Davis.”

Mr. Ross looked up from the sheet of paper upon which he was writing. “So this,” said he, “is the seat in which Davis used to sit ?”

“Yes,” replied Sumner, “it is.”

“And you and the negro you’ve got here want me to get out of it and lot the negro get into it, do you?”

“We do,” answered Sumner.

“Then,” said Ross, taking up his pen, “I’ve only to say that I’ll see you and the negro __________ first.”

For the next two decades, the desk, also known as Desk 60, was relegated to obscurity. Bassett, who worked as the Senate’s assistant doorkeeper until 1895, reportedly resisted the entreaties of “some mighty influential senators” and refused to identify it “for fear the visitors will chip off splinters for souvenirs.” Somehow it was rediscovered in the late 19th century. Yet when it belonged to Sen. Francis Cockrell of Missouri (a former Confederate general) in 1906, a newspaper reported that its history “is known but to a few persons.”

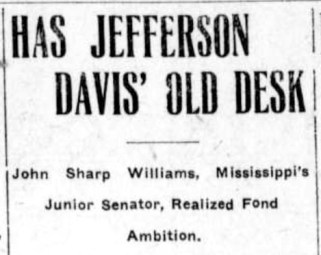

The Hattiesburg News

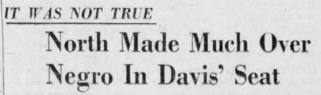

Jackson Clarion-Ledger

While not always held by Mississippi’s senators, the desk came to hold a talismanic allure for them. Sen. John S. Williams was said to have “coveted” it for many years while he served in the House of Representatives. He took his Senate seat in 1911, just as a new wave of monuments to the Confederacy was being erected across the South. Williams received Davis’ desk due to the “determined demands which he made for it in his most unreconstructed and rebellious manner,” as the Saturday Evening Post slyly put it.

His successors also came to revere the desk. “I’d rather sit here than any place in the Senate,” Sen. Pat Harrison said in 1929. Sen. J.O. Eastland, a segregationist who called Black people “an inferior race,” reported in 1942 that it was “the most soughtafter desk in the chamber.” (He lost it to a senator from Maryland.)

As the civil rights movement surged in the 1950s, the desk and its symbolism took on new significance. In 1957, Rex Magee, a white Mississippi journalist still stung by Nast’s 87-year-old cartoon complained that it was nothing but “Radical Republican propaganda” that falsely suggested that Revels had literally sat in the seat of “the martyred president of the prostrate South.” He repeated the claim that “to further humiliate the South,” Reconstruction-era Republicans had tried to give Revels the desk. “Today,” Magee gloated, “a white Senator from the Deep South…sits in the desk where Jefferson Davis once sat.”

In 1963, liberal columnist Drew Pearson imagined the desk as a metaphor for America’s painful path toward racial equality. He related a story in which Vice President Lyndon Johnson pointed out the desk to boxer Sonny Liston during a tour of the Senate chamber. Johnson showed “the big Negro” the scratches left by the Union soldiers, now filled with layers of varnish. “The scars of race hatred have been varnished over several times in this country,” Pearson wrote, “but they are still there.” Perhaps as president, Johnson would “be able with his great persuasion and understanding of human nature and his roots in the South, to make them heal forever.”

US Senate

At that time, the desk had been held for more than a decade by Sen. John C. Stennis, a Democrat who was first elected in 1947 and was known for opposing every piece of civil rights legislation that came before him. He spoke of the desk with reverence. “As one who has as his desk on the Senate floor Jefferson Davis’ own desk,” Stennis told a gathering of the United Daughters of the Confederacy in 1956, “my own mind dwells with singular propriety on the great career the Mississippian carved out for himself as a statesman in that body.”

At a 1961 event commemorating the centennial of Davis’ inauguration as the president of the Confederacy, Stennis gave the drunk history version of how the desk had been damaged. “A Union soldier guarding the Senate Chamber one night was drinking,” he said. After being caught bayonetting Davis’ desk, the remorseful soldier “picked up some of the splintered pieces and tried to restore the desk.” A week after Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1964, Stennis read an article by Magee into the Congressional Record in which he returned to the misconception that Revels took Davis’ seat: “The canard of a Negro succeeding Jefferson Davis in the US Senate lingers through the years.”

As the elderly Stennis went on to be portrayed as a “mild mannered” “pillar of the Senate” and “a legend” (in Joe Biden’s words), his desk was treated as a colorful personal detail with no connection to his segregationist past. After he lost a leg to cancer, Stennis attached a brace to the table so he could stand next to it. “Stennis’ Senate desk, like its present owner, has its scars,” an Associated Press reporter wrote in 1987.

When Stennis retired in 1989, the desk was bequeathed to Sen. Thad Cochran and moved to the Republican side of the chamber. Its relocation, the Economist wrote, was “a symbol of the great shift in southern politics.” It also signaled how little had shifted when it came to Mississippi senators fetishizing a piece of furniture. Stennis’ seat went to Sen. Trent Lott, who, according to Washingtonian, “always coveted [Davis’] desk and hoped to stay in the Senate long enough to have it.” That day never came, though in 1995 Lott and Cochran penned a resolution to ensure that the desk “shall at the request of the senior Senator from Mississippi, be assigned to such Senator for use in carrying out his or her senatorial duties.” It passed with unanimous consent.

The following year, when Lott became Senate majority leader, Cochran stood at the desk and praised his junior colleague as the latest in a line of “outstanding” and “distinguished” Mississippi senators starting with Davis. During his career, Lott did not hide his admiration for Davis. In 1998, he said, “Sometimes I feel closer to Jefferson Davis than any other man in America.”

In 2015, amid calls to remove the statues of Davis and other racists from the Capitol, Cochran suggested that removing the statue might lead to more purges of Davis memorabilia. “I don’t want them taking my desk away either. That’s Jefferson Davis’s desk over there where I’m sitting,” he told Roll Call. “I’m very proud to have that.” “Jefferson Davis is a historical figure to be studied and to be honored,” said Sen. Roger Wicker, who had replaced Lott in 2007. “Was he perfect? No. Was anybody? No.” Wicker now sits at the Davis desk. (His office did not respond to a request for comment.)

Even now, the Davis desk is often treated like it’s just another example of the Senate’s reverence for history and anachronism. Senators do make a big deal over where they sit: The desks formerly belonging to Daniel Webster and Henry Clay are reserved for the senior senators from New Hampshire and Kentucky, respectively. Ohio Sen. Sherrod Brown wrote an entire book about his desk, whose former occupants included Robert F. Kennedy, George McGovern, and both Al Gores. Desk 47, once used by Warren G. Harding and Richard Nixon, has been seen as tainted. (Currently held by Sen. Richard Burr, it may not soon shed its scandalous reputation.)

This all may seem quaint, but senators seek out historically significant seats to signal their aspirations and values. So what is being said by those who have laid claim, through custom and decree, to the desk once used by a white supremacist traitor?

Unlike the desks of the other racists and terrible men who have served in the Senate, the Davis desk has been turned into a tribute to its original holder. It might have been simply left as a relic—nothing more than government property (as Bassett put it) passed from lawmaker to lawmaker. (During his time as a desk-hopping senator, Harry S. Truman sat at the desk with no apparent comment.) Instead, its occupants turned it into a vehicle for rehabilitating Davis’ reputation. Much as the nearly 200-year-old desk has been patched and polished so it might stay in use, Davis’ racism and secessionism have been smoothed over so that 21st century white politicians may praise him without embarrassment. It’s time to look past the varnish.