HRAUN/Getty

Adrienne Moore knew something was wrong. After being diagnosed and successfully treated for ovarian cancer a decade earlier, she recognized the pain and bleeding she began to experience during intercourse, and the sudden irregularity of her periods, as signs of a potentially serious problem with her reproductive health.

Moore, a 45-year-old respiratory nurse from Atlanta, was terrified that her cancer had returned. But when she sought help from her doctors in 2012, she left her appointments with a series of misdiagnoses: perimenopause, cysts, fibroids. “Being in the medical world, I thought I knew how to communicate with my caregivers,” she says. But even as she pressed her fears, it felt like no one was listening.

She returned to her doctors repeatedly over the next three years, but her symptoms didn’t improve. When her employers switched her health insurance plan, and her monthly premium jumped, Moore became unable to afford specialist care. As the pain grew unbearable, she requested sick leave from work. Instead, she was laid off. Her family paid out of pocket for scans and tests that Moore herself ordered. Still, doctors found nothing wrong.

But growing in Moore’s pelvic cavity, across her ovaries and into the endometrium—the lining of her womb—was a disease that could kill her.

Endometrial cancer is the most common type of gynecological cancer in the United States. Four times more common than cervical cancer, and the fourth most common cancer in women, it’s one of the few cancers in the country for which diagnoses and deaths are on the rise. The American Cancer Society estimates that at least 57,000 women will be diagnosed this year, and more than 11,000 will die.

Black women are just as likely to get endometrial cancer as white women, but they are more likely to die from it. “Within every age, within every stage of diagnosis, within every tumor type, black women do worse,” says Dr. Kemi Doll, a gynecologic oncologist at the University of Washington.

Doll has spent the past seven years researching gynecological cancers and investigating the cause of the disparity. She believes that, as with racial discrepancies in other medical conditions, the difference in the endometrial cancer death rate is the result of how the medical establishment treats black women.

To start, black women are less likely than white women to receive an early diagnosis for the disease. As a result, thousands discover they have the cancer only after it has spread, when they have less chance of survival.

That could be because doctors miss early signs of the disease, or because many black women are more reluctant or less able than their white counterparts to seek help from doctors. For many black women, confidence in the health care system has been undermined by decades of difficult experiences. Studies have found that doctors are more likely to view black patients as medically uncooperative, and that diagnostic and treatment decisions are influenced by patients’ race. Black patients consistently report higher levels of dissatisfaction with their care and mistrust of their doctors. Doll says that patients she speaks with frequently describe feeling dismissed, ignored, or overwhelmed. “If you consider a black woman in the US who has had a lifetime of experiences of subpar reproductive health care,” Doll says, “it might not be that a couple of drops of postmenopausal bleeding has you running to the doctor.”

And even those, like Moore, who seek help early for endometrial cancer receive less aggressive care. A recent study conducted by Doll’s team found that black women with health insurance or access to medical care were less likely than white women to receive biopsies that could confirm their cancer earlier. Another found that 40 percent of the black-white mortality gap in endometrial cancer may be due to inequitable surgery rates: research shows that black women are less likely to receive surgery than white women at every stage of the disease, and they are also less likely to receive chemotherapy.

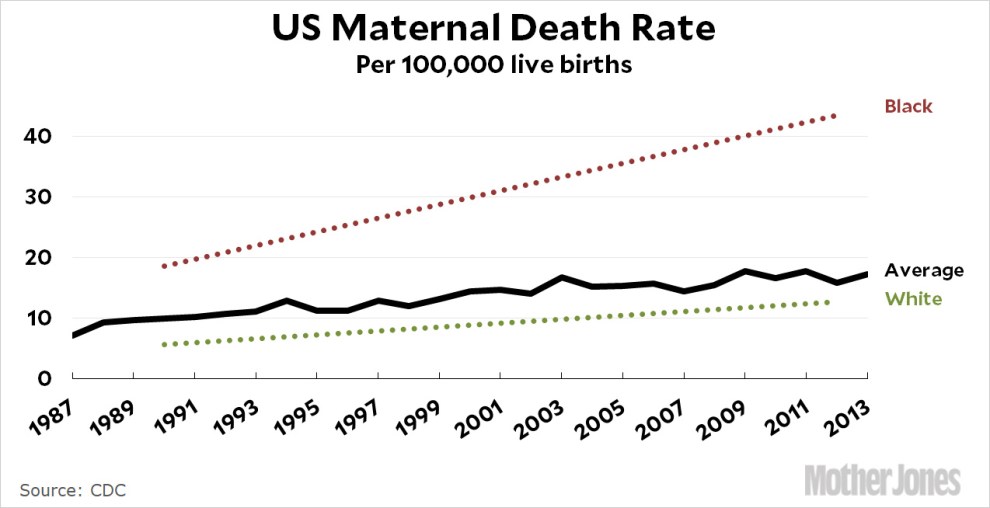

For further proof, Doll points to the racial discrepancies that exist in other diseases. Black women are less likely than white women to be tested for hereditary genetic mutations linked to breast cancer. Black patients with end-stage renal disease are less likely to be considered appropriate candidates for kidney transplants. Compared with white patients, black patients are more likely to die from breast, prostate, and stomach cancer, more likely to develop Alzheimer’s, and more likely to have a stroke. When it comes to maternal care, black women are almost four times more likely to die a pregnancy-related death than white women, and more likely to experience pregnancy complications like preeclampsia, placental abruptions, and postpartum hemorrhage.

“You can either approach it from the standpoint that there is something fundamentally wrong with black women’s bodies, or there’s something wrong with the way we treat black women and their bodies,” Doll says. “We are not going to help women, and we are not going to solve this problem, if we don’t deal with the problem of race and racism.”

Not everyone agrees entirely with Doll’s prognosis. Dr. Rodney Rocconi, interim director of the University of South Alabama Mitchell Cancer Institute, believes that biology plays an important part in endometrial cancer’s mortality disparity. Rocconi points to the fact that black women are more likely to be diagnosed with an aggressive form of endometrial cancer, regardless of how early she is diagnosed.

Rocconi’s research has found that women with a higher percentage of African ancestry are significantly more likely to have a genetic mutation that allows tumors to grow unchecked. Other research corroborates this idea: certain genetic mechanisms that help suppress tumors are less active in black women. Studies of kidney disease and hypertension suggest that genetics may also play part in increasing black people’s risk of developing the illnesses.

Critics argue that research linking race, genetics, and disease veers troublingly close to endorsing theories of eugenics and promoting pseudo-scientific racism. Rocconi agrees that “there’s no such thing as a black gene.” But identifying a concrete link between black women’s genetics and the aggressive tumors they suffer could be the first step in finding a cure. “What’s most exciting to me is that we can target” the biological cause of the disease, Rocconi says. Once the research is confirmed, “we can add a targeted therapy to inhibit that immune pathway, and make patients more likely to respond to therapy.”

But progress is hampered by another racial discrepancy, this time in clinical trials. Black enrollment numbers for early-phase endometrial cancer clinical trials, Rocconi notes, are dismal: For even one white person enrolled, 0.04 black people are. “That first phase in clinical trials helps set the pipeline for agents that can be used in patients,” Rocconi says. “We are self-selecting [therapies] that work in the majority white population.” This is a widespread problem. A recent ProPublica investigation found that in trials for 18 drugs targeting cancers that occur at least as frequently in black people as white, on average only 4.1 percent of participants were black.

To increase participation, Rocconi says, doctors must find a way to garner black patients’ trust in medical institutions. In Alabama, where the infamous Tuskegee syphilis experiment remains in living memory, Rocconi has had success enrolling more black patients in cancer treatment trials thanks to a University of South Alabama peer support program that helps patients understand treatment plans and medications and access things like medical insurance, hospital transportation, and community services. “These were black women who were talking to people from the same community,” Rocconi says. “They were advocates for them.”

Rocconi’s and Doll’s research converge in another way, too: Both researchers believe epigenetics, the idea that social, economic, and cultural inequalities can alter our DNA, might also have a role in explaining why more black women are dying from endometrial cancer. Since the inequalities black women face persist throughout lifetimes, “the resulting epigenetic changes keep accumulating…resulting in poorer health outcomes, including cancer,” among certain racial and ethnic groups, a study co-written by Rocconi asserts. In other words, black women’s genes may predispose them to aggressive endometrial cancer. But those genes have been influenced by generations of inequality.

This is why Doll believes that her patients’ experiences are key. “The genetic information that you’re getting comes from a person who had an experience,” she says. “And if you don’t look at that experience you simply won’t ever know how it may be influencing what you’re seeing on the genetic level.”

Back in Atlanta, Adrienne Moore was determined to find answers to what was ailing her. When she started a new job, a year after being laid off, she used her reinstated health benefits to order a biopsy on one of her cysts. It confirmed what she thought she already knew: She had cancer. But when the oncologist described the disease, she was shocked. She had never heard of endometrial cancer before. Her disease was so advanced, she was diagnosed at Stage 3. She was lucky to survive.

As she finished chemotherapy, Moore joined the Endometrial Cancer Action Network for African-Americans, a national support group founded by Doll. The organization hosts an online community for survivors and an education arm that informs black women about the disease, and its members serve as a research pool for ongoing studies into the cancer’s causes and treatments. Moore, whose cancer is now in remission, is a patient advisor for ECANA and conducts outreach to black women across Georgia.

“There’s such a silence around our reproductive health,” says Moore. She feels she had a lucky escape. “When black women tell me they’ve never heard of endometrial cancer,” she says, “it’s probably because we’ve lost so many to this disease.”