Mother Jones illustration

On April 10, 2018, Facebook co-founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg did something he had managed to avoid in his 14 years at the helm of the tech giant he had built: He testified before Congress. His company had been battered in the preceding months, first by revelations that Russia had used the platform as part of its covert disinformation campaign to help elect President Donald Trump, then by news that the political consulting firm Cambridge Analytica had illicitly harvested the personal data of tens of millions of Facebook users to help Trump win. Senators from the commerce and judiciary committees repeatedly hammered Zuckerberg on these issues.

But three hours into the hearing, Sen. Cory Booker (D-N.J.) opened up a different line of questioning. Facebook, he told Zuckerberg, was becoming a tool of racial discrimination. Rather than fulfill technology’s promise of expanding opportunity, the platform had given advertisers “more sophisticated tools with which to discriminate.” Booker spent his allotted five minutes asking Zuckerberg about Facebook ads that discriminated against minorities in housing, employment, and loans. Toward the end, he said to Zuckerberg, “I’m wondering if you’d be open to opening your platform for civil rights organizations…to really audit what is actually happening.”

“Senator,” Zuckerberg responded, “I think that’s a very good idea.”

It was a blink-and-you-miss-it moment. But sitting at her computer watching a livestream of the hearing, Brandi Collins-Dexter knew it was a triumph: the culmination of years of advocacy and civil rights advocates’ best shot at forcing Facebook to investigate the ways its platform harmed people of color. Now she and her colleagues at the racial justice group Color of Change, where she served as senior campaign director, had to make sure Zuckerberg kept his word.

Famously launched from Zuckerberg’s Harvard dorm room in 2004, Facebook now has more users than Christianity has adherents. In 15 years of unregulated growth, it has become a place where companies can market fancy houses to white people and junk food to black children, where hate speech is amplified and the right to vote is suppressed. As the problems multiplied, some advocates and watchdogs came to believe that the repeated civil rights violations on the platform were rooted in a deliberate decision by Facebook to ignore evidence of advertising discrimination, voter suppression, and the proliferation of hate speech and extremism.

Since the fall of 2016, Color of Change and a growing chorus of civil rights groups have pressured Facebook to conduct an independent, in-depth audit of how the company’s policies affect African Americans, Muslims, women and other communities protected by federal civil rights laws. The purpose is to pull back the curtain on one of the world’s most secretive companies so that both advocates and Facebook executives can understand—and begin to rectify—the ways Facebook’s policies, enforcement, technology, and internal culture are hurting minorities and women. The Center for Media Justice’s Erin Shields, who along with other advocates attended a series of 2018 meetings with Facebook representatives in Washington to push for an audit, put it more bluntly: “It’s so that we can have a greater understanding of how Facebook is actually fucking with our communities.”

Color of Change, founded in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina to use the internet to organize racial justice campaigns, began targeting Silicon Valley in 2014, when the group turned its focus to the lack of diversity in tech. Over the past five years, Color of Change and dozens of other activists lobbied Facebook on issues of discrimination that continued to crop up on the platform. Year after year, Facebook took no meaningful action.

According to nearly 20 civil rights advocates and watchdogs who spoke to Mother Jones, a pattern emerged. Civil rights advocates would raise concerns with Facebook, the company would welcome them into a meeting, and nothing would come of it. “You can talk to them all day until you’re blue in the face about an issue,” says Shields, but nothing happens unless outside forces bring public scrutiny to Facebook.

Now, those forces came in the form of the Russia scandal and the Cambridge Analytica revelations. Suddenly, Facebook was on the defensive.

Zuckerberg’s testimony before Congress was just two weeks away. “We knew this would be our one shot to get Mark Zuckerberg on the record to agree to a civil rights audit,” says Collins-Dexter. The success of years of advocacy by civil rights groups hung in the balance. They got to work.

The civil rights laws of the 1960s and ’70s gave Americans of color, all women, and religious minorities sweeping new protections against discrimination in employment, housing, and credit. To make these protections meaningful, Congress prohibited discrimination in advertising in those areas. Ads for houses and mortgages and jobs could not be directed toward only white audiences, nor could ads for high-interest loans or poverty-wage jobs target people of color. But Facebook provided an innovative new way around these rules.

In March 2016, an executive at Universal Pictures named Doug Neil hosted a panel at the technology conference South by Southwest in which he revealed the secret to the box-office success of the recent film Straight Outta Compton. Since 2014, Facebook had been sorting its users into “ethnic affinity” groups, guessing their race based on the pages they liked, their interests, and other factors. The result was the most accurate race-targeting data commercially available. Advertisers could select—or exclude—entire racial groups from viewing their ads.

These tools allowed Universal to market one trailer to black people and an entirely different one to white people. Black users saw an homage to the pioneering hip-hop group N.W.A, featuring interviews with original band members Dr. Dre and Ice Cube describing their work as “protest art” against the conditions black people endured in 1980s Los Angeles. Viewers who Facebook coded as white viewed a trailer that depicted the rappers as semi-automatic-toting gangsters clashing with cops and rioting in the streets.

Rachel Goodman, an attorney at the American Civil Liberties Union, saw the Straight Outta Compton presentation and immediately realized that its implications went beyond ticket sales. If advertisers were also using Facebook’s ethnic affinity labels to find job applicants, home buyers, or credit card users, federal civil rights laws were being violated. Facebook had gone down a dystopian path where white users might see ads for white-collar jobs, houses in sought-after neighborhoods, and low-interest loans, while people of color would see ads for low-wage jobs, housing in impoverished areas, and predatory loans that would drain wealth from their communities.

It took multiple phone calls between the ACLU and members of Facebook’s Washington, DC, policy shop before the DC team acknowledged that racial targeting could lead to discrimination, according to one participant in these conversations. “It’s true that we had calls with the groups before we began to develop solutions,” says Facebook spokeswoman Ruchika Budhraja. “In any engagement, we start by trying to understand the perspective of the groups and the nature of the issues they care about.”

There was no evidence that any housing, credit, or job ads had actually been posted to the site that excluded certain races or genders. But then again, if there had been any, it would have been almost impossible to know without access to internal Facebook data. Effectively, an advertiser would have had to come forward to confess to illegally targeting ads by race. (Months later, lawyers did find African American plaintiffs who alleged that although they were actively looking for jobs, Facebook did not show them employment ads. The case was settled, leaving no public account of whether the plaintiffs were able to prove they’d been excluded.)

In the spring of 2016, the ACLU brought together a small working group of tech experts and civil rights organizations, including the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund (LDF) and the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, to work with Facebook to remove racial targeting from housing, employment, and credit ads. They proposed a straightforward solution to avoid violations of civil rights law: Set up a different portal for housing, employment, and credit ads that do not allow targeting by race.

But Facebook pushed back. Advertising is how Facebook makes money, and one participant in the meetings came away with the impression that the company was trying to avoid jeopardizing revenue. “They were very much not wanting to add new fields or new steps to the process of buying and placing ads,” the participant recalls. “They were pretty blunt about that with us: We’re not going to add whole new screens and new options that everyone has to go through. Because every time we do that, we lose a fraction of a percent of the advertisers.” Facebook’s representatives, the participant says, also expressed concern that if the company started putting up legal notices in the advertising portal, “you might scare off lower-level marketing staff that use the Facebook interface.”

Budhraja, the Facebook spokeswoman, flatly denies that financial motivations guided the company’s response to the advocates’ recommendations. “We never objected to any of their ideas based on speculation about advertiser reaction,” she says. Facebook, she maintains, was “frank with the groups about the technical challenges of implementing some of the proposals we had discussed.”

Then, on October 28, 2016, ProPublica published a bombshell exposé detailing what the ACLU’s Goodman and her colleagues already knew: that in legally protected industries, Facebook allowed ads to be racially targeted. Under public pressure to fix the problem, Facebook sprang into action. It created an algorithm that would scan ads after they were submitted and block ethnic-affinity targeting for ads in housing, employment, and credit. It would also prompt people placing ads in these areas to self-certify compliance with Facebook’s terms of service and the law. The civil rights groups urged Facebook to implement it, which Facebook did in February 2017.

But another ProPublica investigation in November 2017 showed that it was still easy for housing advertisers to discriminate based on race. Reporters had purchased rental housing ads and used the “exclude people” drop-down menus to prevent African Americans, Jews, Spanish speakers, people interested in wheelchair ramps, and other groups from seeing the ads. Facebook never prompted the reporters to certify compliance with the law, and all of the ads were approved.

The story also revealed that Facebook allowed advertisers to target users by zip code to advertise housing, an easy proxy for race. When an advertiser selected a zip code to exclude from a housing ad, Facebook’s mapping tool would draw a red line around it. The Jim Crow practice of redlining—when banks routinely denied home loans to African Americans in segregated neighborhoods that US government surveyors had marked on maps as “hazardous” with red ink—was reanimated in digital form.

ProPublica’s investigations prompted a class-action lawsuit against Facebook in California and a suit from the National Fair Housing Alliance in New York, as well as ACLU complaints with the federal Equal Employment Opportunity Commission over age and gender ad discrimination. Facebook moved to have the two lawsuits dismissed, arguing that the advertising tools were not harming people. Even if the law had been violated, Facebook lawyers claimed, the advertisers were “wholly responsible for deciding where, how, and when to publish their ads.” Facebook was just the platform.

But technology experts say that’s simply not the case. On top of the targeting metrics that advertisers set, Facebook layers its own algorithms to display ads to the users most likely to click on them. These algorithms sometimes exclude users on the basis of race or gender, even when the advertiser never intends to discriminate.

Miranda Bogen, who studies artificial intelligence and discrimination at the tech nonprofit Upturn, gives the example of an employer who wants to advertise a computer programming job to people with a college degree. More men might feel qualified for that job and click on the ad. Facebook will learn from this that men are better targets for the ad and then show it more often to people who resemble those already clicking—namely men. Upturn, which was involved in the 2016 meetings between Facebook and civil rights groups over ad targeting, recently placed test ads on Facebook. Ads for lumber industry jobs reached 90 percent men, those for supermarket cashiers reached 85 percent women, and those for taxi company positions reached 75 percent African Americans, even though the target audience Upturn specified was the same for all three ad types.

“Facebook is learning from people’s behavior and then following that path,” Bogen says. “So if certain people are more likely to engage with certain content, that type of content is going to be shown more regularly to people who Facebook sees to resemble one another.”

One of Facebook’s most valuable tools, called “Lookalike Audience,” builds an audience for a particular ad when the advertiser doesn’t know whom to target. These advertisers come to Facebook seeking to expand their client base or recruit employees. They give Facebook the contact information of current clients or workforce and allow the company to use that knowledge to build an ad audience that resembles them. If those people are primarily white men, Facebook will seek out other men who the platform presumes are white—leaving out users it has labeled as ethnic minorities and women.

When civil rights advocates have complained about these practices, Facebook executives have implied that these critics simply don’t understand how the company works. “With technology companies, the additional challenge is, they get to say, ‘You just don’t understand the technical difficulties of doing what you want to do. You just don’t get what we’re doing here,’” says Todd Cox, former director of policy at LDF. “No, I get what you’re doing here: You’re selling ads.” In 2018, Facebook made $55.8 billion. Ninety-nine percent of that came from selling ads.

Civil rights groups have been trying to persuade tech companies to crack down on internet hate speech for most of a decade. In 2012, the Anti-Defamation League began organizing a series of meetings with executives from Facebook, Google, Microsoft, Twitter, Yahoo, and YouTube about the proliferation of hate speech online. The ADL flew in Mike Whine, a British expert on anti-Semitism. At the first meeting, at Stanford University, Whine got the sense that the Silicon Valley executives had never considered that their platforms could be used for evil. They were in a “Californian bubble,” he says, “unaware of the effect of hateful messages online, or even of what was going on” on their own platforms.

Meanwhile, the Black Lives Matter movement was emerging, and Facebook was a critical organizing tool—but also a battleground. When BLM activists posted pictures and events, white supremacists commented with racial slurs, images of nooses, and other threats. By late 2015, Malkia Cyril, a BLM activist and executive director of the Center for Media Justice, was spending around two hours every day flagging threatening and racist content to Facebook for removal. Finally, Cyril reached out to Kevin Martin, then vice president for mobile and global access policy at Facebook, whom Cyril knew from his previous work at the Federal Communications Commission, where he served as chairman under President George W. Bush.

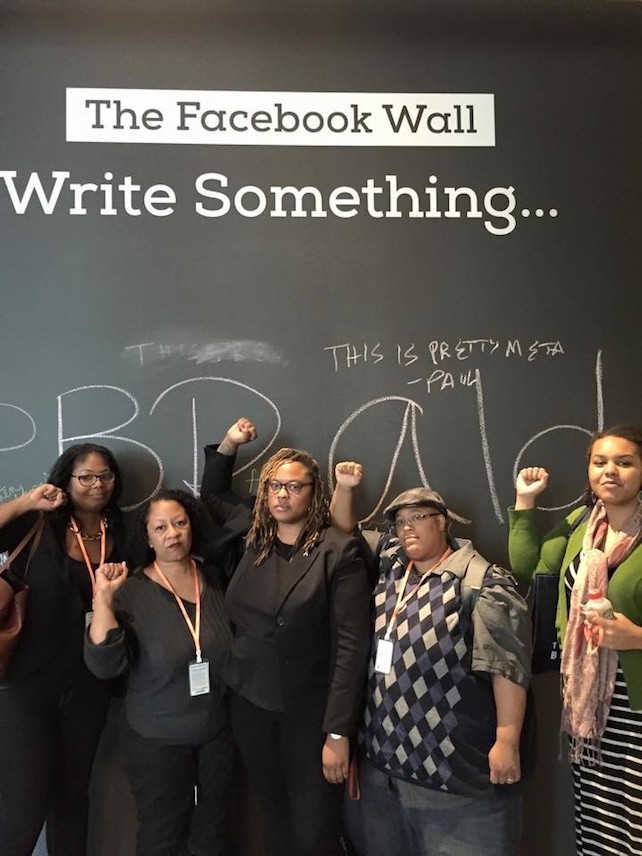

Martin helped set up a meeting, and on February 11, 2016, Cyril, Color of Change’s Collins-Dexter, and three other black civil rights advocates were shown into a conference room at Facebook’s headquarters in Menlo Park, California. They were there to meet the company’s head of global policy, a former federal prosecutor named Monika Bickert. Since 2013, Bickert has been in charge of Facebook’s “community standards,” rules for what can and cannot be posted on the platform.

The advocates arrived with a list of demands. They wanted Facebook to clarify its definition of hate speech and address what they perceived as its disproportionate removal of posts and pages put up by black people for allegedly violating its standards, while not removing posts that threatened them. A month earlier, Facebook had taken down the Minneapolis BLM chapter’s page, along with some of its organizers’ profiles, with a vague explanation about violating Facebook’s standards. (After the BLM chapter appealed, Facebook restored its page.) One attendee, Tanya Faison, the founder of the Sacramento BLM chapter, was stalked at her home and at rallies after a militant gun enthusiast put her address, phone number, and picture on Facebook. Faison says she and her friends had reported the post to Facebook, but it never came down.

According to Cyril, Bickert and her team said they did not want to censor political speech. Cyril, Collins-Dexter, and another attendee say the Facebook team also claimed that its content moderators, largely in Southeast Asia, failed to remove hate speech because they were not familiar with the symbols and buzzwords of American racism. The meeting resulted in only one change: Facebook designated several Black Lives Matter pages as “verified,” a move that activists hoped would make moderators less likely to censor them.

Bickert says she does not recall this specific meeting, but she notes that Facebook has hired more US-based content moderators to tackle hate speech. Still, she acknowledges that free speech can’t really exist on the platform if it’s met with abuse. “For many people, creating that safe environment and placing some limits on what you can say on Facebook is actually vital to allowing people a voice,” she says.

The activists left the meeting feeling stymied. “It felt like an obligatory meeting where Facebook told us, in very nice words, that they really couldn’t do anything to help us,” says Shanelle Matthews, who attended in her role at the time as communications director for the Black Lives Matter Global Network.

As the activists exited, they passed a chalkboard wall where Facebook employees are encouraged to scribble notes. They took a few photos in front of the wall, including one in which they each raised a fist as a symbol of the Black Power movement. Then Faison wrote “Black Lives Matter” on the board.

After they left, an employee crossed out Faison’s message and wrote “All Lives Matter.” Another employee changed it back to “Black Lives Matter,” which was crossed out again and replaced with “All Lives Matter.” This went on for weeks, until the escalating battle leaked to the press. Zuckerberg ultimately organized a company town hall to educate employees on the BLM movement. As Facebook dithered in confronting racism on its platform, its own staff couldn’t agree on whether black lives mattered.

Activists Brandi Collins-Dexter, Tanya Faison, Shanelle Matthews, Malkia Cyril, and Sarah Howell pose in front of Facebook’s chalkboard. Credit:

Malkia Cyril

Six months later, on August 1, 2016, a Baltimore police officer shot and killed a 23-year-old African American woman named Korryn Gaines. Gaines had been broadcasting, via Facebook Live, an hours-long confrontation at her apartment with the cops, who were trying to serve her a warrant for failing to show up in court for charges stemming from a traffic violation. Gaines had a shotgun and her five-year-old son with her, and it was clear that she was mentally ill and not cooperating, so the police petitioned Facebook to deactivate her account in what police said was an attempt to de-escalate the conflict. Shortly after her live feed disappeared, an officer shot Gaines five times and shot her son in the face and the elbow.

The shooting gave Color of Change a greater sense of urgency about Facebook’s impact on the black community. Three months later, Color of Change and the Center for Media Justice sent Facebook a letter asking the company to clarify its policies on content censorship. The letter, which was signed by 75 other progressive groups, urged Facebook to “undergo an external audit on the equity and human rights outcomes of your Facebook Live and content censorship and data sharing policies” and then “institute a task force for implementing the recommendations.” Facebook responded that its policies had already been approved by a coalition of technology companies and nonprofits.

Meanwhile, the civil rights group Muslim Advocates had been pushing Facebook for years to address anti-Muslim content, also without much success. In the summer of 2017, the anti-Muslim group ACT for America used its Facebook page to organize street protests in 28 cities to intimidate Muslims during the holy month of Ramadan. Members of right-wing militia groups were invited to provide security, and protesters in several cities came armed. Muslim Advocates urged Facebook to take down the group’s page, which was littered with threatening messages referring to Muslims as “terrorists,” “maggots,” and “a cancer to our Nation.” Facebook declined to do so. In October 2017, a year after Color of Change made its audit demands, Muslim Advocates wrote its own letter to Facebook demanding a civil rights audit, with 18 other groups signing on.

The timing of the letter was fortuitous. Outside events made it impossible for Facebook to continue punting on the issue of discrimination. Earlier that month, chief operating officer Sheryl Sandberg had flown to Washington for damage control after Facebook had disclosed that the Internet Research Agency (IRA), a shadowy Russian company working for the Kremlin, had purchased more than $100,000 in Facebook ads during the 2016 presidential election. The ads reached 10 million people with messages aiming to divide the electorate on hot-button issues, including immigration, race, LGBT rights, and gun control. A Columbia University study released that month had found that Facebook posts by IRA employees, posing as ordinary Americans and seeking to promote Trump and suppress votes for Hillary Clinton, had likely reached billions of people.

African Americans were the primary target. Two reports commissioned by the Senate Intelligence Committee found that sowing confusion and division among African Americans was the centerpiece of Russia’s social media strategy to help Trump. “The most prolific [Russian] efforts on Facebook and Instagram specifically targeted Black American communities and appear to have been focused on developing Black audiences and recruiting Black Americans as assets,” the think tank New Knowledge concluded in one of the reports. Several accounts on Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube feigned allegiances with Black Lives Matter, then discouraged their hundreds of thousands of followers from supporting Clinton. The IRA’s “Blacktivist” page, with 360,000 likes, posted messages like “NO LIVES MATTER TO HILLARY CLINTON. ONLY VOTES MATTER TO HILLARY CLINTON” and “NOT VOTING is a way to exercise our rights.” Other accounts directed the black vote to third-party candidate Jill Stein.

“Race was the back door that the Russians used to get into the last presidential election,” says former LDF lawyer Cox, who met with Sandberg. In the 2016 election, Color of Change president Rashad Robinson has said, “Russians seemed to know more about black people than Facebook.”

When Color of Change began asking Facebook for a civil rights audit, it already knew what a successful one could accomplish. In July 2015, a 23-year-old black woman named Quirtina Crittenden had started the viral hashtag #AirbnbWhileBlack, bringing more attention to the discrimination that black people faced on the housing rental site. Crittenden’s booking requests were routinely denied until she shortened her profile name to Tina and swapped out her photo for a city skyline.

Airbnb hired Laura Murphy, former director of the ACLU in Washington, DC, to lead an audit.* Released to the public in September 2016, the audit recommended making guests’ photos less prominent on the page, as well as a comprehensive nondiscrimination policy and a commitment to staff and user diversity. “They set up public benchmarks and intentions that allow us and other advocates be able to hold them accountable,” says Collins-Dexter, who still meets with Airbnb on a regular basis.

Airbnb had not just a moral but a financial incentive to keep black users on its platform. But Cristina López G., who tracks online extremism for the liberal watchdog group Media Matters, believes Facebook has a financial incentive not to address racially motivated hate speech and extremism. Studies have shown that provocative content causes users to spend more time on social media platforms than uncontroversial material, generating more clicks and revenue. “The outrage moves a lot of the traffic,” says López.

Users’ interactions with extremist messages can also be valuable data for Facebook. “There will be a political campaign in the future that will want to target people that share those interests,” Lopez says. “At the end of the day, users on Facebook are just data points.”

Budhraja, the Facebook spokeswoman, denies that Facebook has a profit motive to allow extremist content on the platform. Leaving hate speech up on the site “will ultimately make people feel less comfortable and less willing to share,” she says. “So I’d actually argue that the opposite is true—the long-term effect of leaving hateful content up is that it has the potential to reduce profitability.” She says Facebook immediately removes content that violates its hate speech policies unless an error in enforcement occurs.

While civil rights groups struggled to get Facebook to address their complaints, conservatives had much better luck. Right-wing media figures found a champion in Facebook’s DC policy shop, which former employees describe as the company’s conservative enclave. In 2011, to curry favor with the new Republican majority in the House, Facebook hired Joel Kaplan, former deputy chief of staff for policy to President George W. Bush, as vice president of global public policy in Washington. (Kaplan’s influence came under scrutiny last year when he attended the confirmation hearing of his friend Brett Kavanaugh to support the embattled Supreme Court nominee.) The move was meant to balance the seemingly liberal leanings of Zuckerberg and Sandberg, but it had an unintended consequence: creating a fast track for conservative complaints to Facebook.

In May 2016, Gizmodo reported that Facebook employees had suppressed some conservative content on the platform’s “trending topics” feature, provoking outrage on the right. Facebook denied any bias and conducted an internal investigation that found no evidence of prejudice. To calm the storm, Kaplan arranged for Zuckerberg and other Facebook executives to meet with Glenn Beck, Tucker Carlson, billionaire Trump-backer Peter Thiel (who was also a Facebook board member), and a dozen other prominent conservatives. Three months later, Facebook put algorithms in charge of the trending topics and fired the contractors in charge of making sure the news items the platform was promoting were legitimate. According to a BuzzFeed News analysis, clicks and shares of fake news stories promoting Trump nearly tripled after the change.

Facebook seemed to be sending a message to conservative writers, politicians, and internet trolls: If they simply alleged bias, they could get Facebook to accede to their demands.

In late 2017, the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights organized a series of meetings between Facebook and a coalition of civil rights advocates. Activists hoped a group effort might help them convince Facebook finally to undertake an audit.

Their optimism was short-lived. After an initial meeting, Facebook structured each subsequent conversation around a single topic: election interference in February, data privacy in March, hate speech in April. Advocates arrived at each meeting at Facebook’s DC office to find a classroom-style seating arrangement and a presentation on Facebook’s approach to the day’s subject. The sessions were hosted by Monique Dorsainvil and Lindsay Elin, part of a new progressive outreach team Facebook had created, alongside a conservative counterpart.

The meetings grew tense. At the February and March gatherings, advocates cut off the presenters and tried to discuss solutions. Several groups asked about the audit. Muslim Advocates asked at each meeting why the anti-Muslim group ACT for America was still on the platform.

“Groups felt like they were not making any headway,” recalls one advocate, who asked to remain anonymous because the meetings were off the record. “There was a little bit of a Groundhog Day aspect to this.” At the April gathering, several advocates said that if Facebook did not take up a civil rights audit, they no longer saw a reason to meet.

But the advocates had another opportunity to make their case. Zuckerberg was about to testify before Congress for the first time. Color of Change scrambled to get lawmakers to do what it couldn’t accomplish in its meetings with Facebook: pin Zuckerberg down on a civil rights audit. Collins-Dexter and a colleague sent a memo to eight Democratic senators and representatives who would be questioning Zuckerberg, laying out a series of queries that would force the Facebook CEO to address his company’s civil rights record and commit to an audit. Most of the offices thanked Color of Change for the memo but took no further action. One Senate office, however, expressed particular interest.

As a relatively junior senator, Cory Booker wouldn’t get to ask a question until hours into the hearing, when Russian election interference and Cambridge Analytica would be exhausted topics. His aides had been looking into other issues that Booker could raise. That’s when they received Color of Change’s memo.

Collins-Dexter and a colleague spoke with Booker’s staff on the phone and in person about Facebook’s civil rights problems and the need for an audit. But it was still unclear what the senator would ask, and as the hearing entered its third hour without any mention of an audit, she was beginning to lose hope. When Booker finally asked about it, Collins-Dexter says, we “knew we had our moment.” On a phone call shortly after the hearing, Color of Change gave Booker’s staff the parameters of what it considered an acceptable audit: one conducted by a third party and that engaged civil rights groups, and that would become public. Booker’s office followed up with Facebook about the audit, and a member of Facebook’s policy team confirmed to a senior Booker aide that the company would pursue the audit.

On May 2, Facebook announced publicly that it would conduct a civil rights audit, helmed by Murphy, the former ACLU director who had led the Airbnb audit. But on the same day, Facebook also announced a second audit into anti-conservative bias, led by former Sen. Jon Kyl, an Arizona Republican. The conservative audit felt like a slap to civil rights groups. Rather than treat civil rights as a moral imperative, they believed, Facebook was casting it as a liberal priority that had to be counterbalanced by a conservative one.

“A lot of groups that we were organizing with were incredibly pissed off,” says the Center for Media Justice’s Shields. “Because it equated something very serious, and also something that should be nonpartisan, which is civil rights, to something as silly as a conservative bias on their platform.”

As the audits got underway, Facebook continued its efforts to balance the demands of civil rights advocates and conservatives. In September, the company brought in the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights to train its election monitoring team to detect voter suppression. But it also provided training on detecting voter fraud, which is exceedingly rare yet hyped as a major problem by some conservative activists and politicians who favor policies that make it more difficult to vote.

Facebook remained evasive when pressed by Color of Change and others on whether it would release the results of the civil rights audit. The 2018 midterm elections were nearing with a sense of urgency about voter suppression, and at least the audit was addressing that. The selection of Murphy to conduct the audit gave advocates hope that Facebook was finally making an honest effort to tackle discrimination.

Two weeks before Thanksgiving, Collins-Dexter was heading home to Chicago when she got a call from an activist named Sarah Miller with Freedom From Facebook, a campaign lobbying the government to break up Facebook. Miller had learned that the New York Times was about to publish a story that would concern Color of Change. To Collins-Dexter, the warning sounded ominous.

The Times investigation, published a few hours later, revealed that during the time Color of Change had been meeting with Facebook, the company had hired a Republican opposition research firm to try to discredit the group and other Facebook critics. The firm, Definers Public Affairs, had been pushing the media to investigate the group’s financial ties to liberal donor George Soros, who is frequently portrayed on the right as the puppet master of progressive politics, sometimes in attacks tinged with anti-Semitism. According to Federal Election Commission filings, Soros gave $400,000 to Color of Change’s political action committee in 2016 and $50,000 in 2018, but he is not the PAC’s biggest funder. (That distinction goes to Facebook co-founder Dustin Moskovitz. It’s possible that Soros also donated to Color of Change’s nonprofit arms, but Color of Change declined to disclose donor records.)

Suddenly, Robinson, Color of Change’s president, understood why reporters had begun to ask him in recent months about Soros. Facebook had not only tried to discredit a civil rights group, but it had done so by providing ammunition for the type of bigotry that Color of Change was urging it to take seriously. “While we were operating in good faith trying to protect our communities, they were stooping lower than we’d ever imagined, using anti-Semitism as a crowbar to kneecap a Black-led organization working to hold them accountable,” Robinson said in a scathing statement. Any trust that Facebook and the civil rights advocates had built over the first few months of the audit process was gone.

Sandberg insisted in a post on Facebook that it “was never anyone’s intention to play into an anti-Semitic narrative against Mr. Soros or anyone else.” She added, “The idea that our work has been interpreted as anti-Semitic is abhorrent to me — and deeply personal.” Facebook fired Definers Public Affairs.

On a phone call in December, Robinson says, Sandberg assured him that she would personally take responsibility for the audit. It’s a commitment that may become advocates’ best hope for a meaningful investigation of the company’s civil rights problems, as Sandberg has been pressured to tie her own ambitions to the audit’s success. Laura Murphy says Sandberg is “very involved” and “very hands on” with the audit. If the audit’s scope is narrow, if its results are buried, or if the resulting reforms are inadequate, Sandberg will be left to explain why.

But many civil rights advocates say they’ve lost faith that Facebook will voluntarily make its platform safer for people of color. Increasingly, advocates are lobbying Congress and the Federal Trade Commission to regulate the tech giant, concluding that Facebook has proven more receptive to threats from Washington than pleadings from advocates. Color of Change, convinced that Facebook will not seriously tackle civil rights as long as Zuckerberg controls a majority of the Facebook board’s votes, is also pushing a resolution at Facebook’s May 2019 shareholder meeting to replace him as chairman of the board. “We’re not foolish enough to believe that Facebook can self-regulate,” says Collins-Dexter.

The audit is ultimately an exercise in self-regulation: It will only lead to as much change as Facebook allows. Murphy’s final audit report will include findings about the impact of Facebook’s policies on civil rights and recommendations to the company on improving its handling of voter suppression, hate speech, discrimination in advertising, and Facebook’s internal diversity and culture. Murphy aims to produce an initial report on her activity in June and the final report in December. In conducting the audit, Murphy has met with more than 90 civil rights groups and relayed their concerns to Facebook executives and engineers. Murphy says she will consider the audit a success only if Facebook adopts her suggestions, including company-wide policies to prevent civil rights violations.

Facebook executives say the start of the audit compelled the company to implement a policy to ban ads that misrepresent the voting process, such as by claiming that people can vote by text, or suggesting that individual votes don’t matter. The policy also requires Facebook to send misinformation about voting to third-party fact-checkers.

On March 19, Facebook settled three lawsuits and two EEOC complaints involving ad discrimination. It agreed to implement major changes to its ad tools, including the creation of a separate portal for ads in housing, credit, and employment that will prevent users from being targeted based on race, gender, age, disability, and other protected characteristics—the exact change that the ACLU’s working group had proposed three years earlier. It also agreed to limit the ways the “Lookalike Audience” tool excludes protected classes of people, although the settlement did not mandate changes to other Facebook algorithms that skew the audience for ads along racial and gender lines.

“What I feel like we learned from this process is that these tech companies are huge ships, and litigation may really be the only tool that can turn the ships effectively,” says the ACLU’s Goodman, “even when there are individuals in the company who see the problem and would like to fix it.”

A week after the settlements, Facebook announced it would begin to block content that praised white nationalism—a change that Budhraja and Murphy say resulted from the audit. But it quickly became evident that its new policy fell short of banning all white nationalist content. For example, Facebook defended its decision not to remove a video by self-declared Canadian white nationalist Faith Goldy in which she did not explicitly mention white nationalism but railed against people of color and Jews and bemoaned that they were “replacing” white populations in North America and Europe. After a public outcry, Facebook reversed course and removed Goldy’s account.

Advocates point to the audit as a sign that they’ve finally made progress with Facebook. But after years of setbacks, they’re reserving judgment until they see what the audit actually accomplishes.

Facebook seems “a little more willing to change,” says Francella Ochillo, vice president for policy and general counsel at the National Hispanic Media Coalition, who participated in the 2018 meetings with Facebook. “But I think also you have to put it in perspective. It took hearings, it took Cambridge Analytica, it took the New York Times, it took all of those things to get somebody to say, ‘I’m listening.'”

Correction: An earlier version of this article mischaracterized the process by which Laura Murphy was brought on to conduct the Airbnb audit.