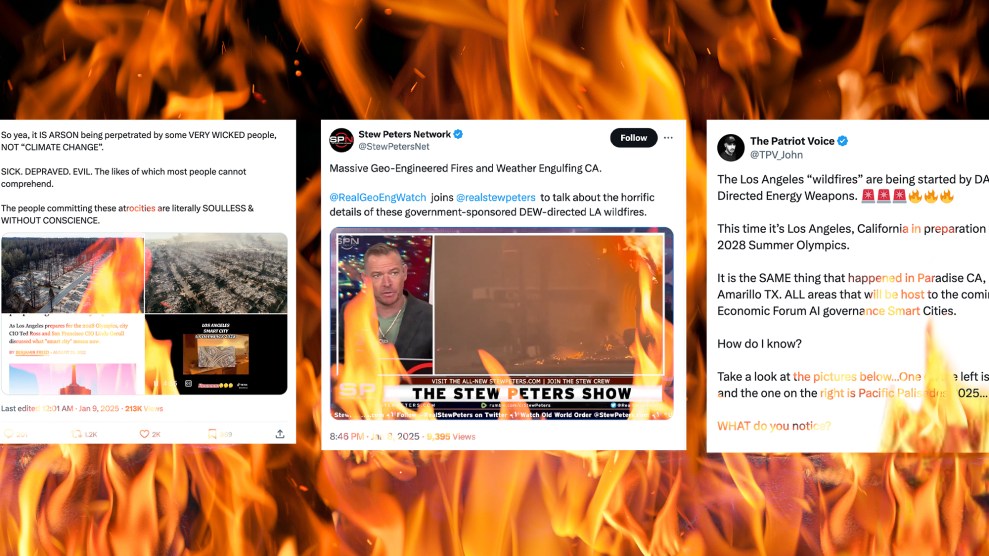

Desmond Meade fills out a voter registration form with his wife, Sheena, at the Supervisor of Elections office on January 8.John Raoux/AP

On Tuesday morning, Desmond Meade went down to the the Orange County elections office in Orlando, Florida, and registered to vote for the first time in decades. Since being released from prison, where he was held on a gun possession charge, in 2005, Meade had been unable to vote because of a Florida law preventing ex-felons from casting a ballot even after they’d paid their debt to society.

In 2018, Meade—now president of the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition (FRRC)—led the effort to pass a ballot initiative overturning the felon disenfranchisement law. It passed on November 6 with 64 percent of the vote. The initiative, known as Amendment 4, went into effect Tuesday morning.

“It was a very, very emotional moment,” Meade said on Facebook after he submitted his voter registration form, his eyes welling up with tears. He was surrounded by his wife and kids and wore a “Let My People Vote” t-shirt. “Across the state of Florida, our democracy is being expanded. That’s a great thing.”

Desmond Meade, who led the years-long effort to return the right to vote to 1.4M former felons in Florida, registered this morning at the Orange County elections office pic.twitter.com/lmyCTuhJeD

— Steven Lemongello (@SteveLemongello) January 8, 2019

Amendment 4 automatically restores voting rights to people with felony records who have completed their full sentences, except those convicted of murder or a sexual offense. Before it passed, Florida was one of only four states that prevented ex-felons from voting, which blocked 10 percent of Floridians from casting a ballot, including 1 in 5 African Americans. The enactment of Amendment 4 could lead to the largest increase in new voters in the state since the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The passage of Amendment 4 was particularly remarkable given that Florida elected a Republican senator and a Republican governor in 2018 who both opposed restoring voting rights to ex-felons. Amendment 4 attracted significant support from Republicans in Florida, even as their party invested heavily in making it harder to vote nationwide. In a huge expansion for voting rights, eight states approved ballot initiatives in 2018 to make it easier to vote and harder to gerrymander.

A huge and improbable coalition supported Amendment 4, ranging from the American Civil Liberties Union to the Christian Coalition to the Koch brothers’ political network. “We are fighting just as hard for that person that wishes he could vote for Donald Trump as that person who wanted to vote for Barack Obama or Hillary Clinton,” Meade told me when I visited Florida in August. “We don’t care about how a person may vote. What we care about is that they have the ability to vote. That is our compass.”

Meade’s own story was equally remarkable, as I reported for Mother Jones:

On a muggy August day in 2005, Desmond Meade stood in front of the railroad tracks north of downtown Miami and prepared to take his life. He’d been released from prison early after a 15-year sentence for gun possession was reduced to three years, but he was addicted to crack, without a job, and homeless. “The only thing going through my mind was how much pain I’d feel when I jumped in front of the oncoming train,” Meade said. “I was a broken man.”

But the train never came, and eventually Meade walked two blocks to a drug treatment center and checked himself in. He got clean, enrolled in school, and received a law degree from Florida International University in 2014. Meade should have been the archetypal recovery success story—“[God] took a crackhead and made a lawyer out of him,” as he put it. But he’s not allowed to practice law. And when his wife ran for the Florida House of Representatives in 2016, he couldn’t vote for her. “My story still doesn’t have a happy ending,” he said. “Because despite the fact that I’ve dedicated my life to being an asset to my community, I still can’t vote.”

Meade’s unlikely partner in the felon restoration effort was Neil Volz, a former chief of staff for Republican Rep. Bob Ney of Ohio and a top lobbyist for onetime superlobbyist Jack Abramoff. Volz was a GOP power broker in Washington until Abramoff’s pay-for-play lobbying scheme unraveled and Volz pled guilty in 2006 to conspiring to corrupt public officials. He lost the right to vote when he moved to Florida afterward, and registered for the first time in over a decade on Tuesday.

Today…no words. Grateful to God and everyone who has fought to protect our ability to vote!! @sheena_meade @desmondmeade @JessiChiappone @FLRightsRestore pic.twitter.com/CmPmEovZbl

— Neil Volz (@Volzie) January 8, 2019

“Year by year, when you don’t have the vote, you really take on an appreciation for having the ability to vote,” Volz, who’s now the political director for FRRC, told me after he registered at the Lee County elections office in Fort Myers. Similar stories of ex-felons registering across the state circulated widely on social media.

Corri Moore, 42, was one of the first people downtown to register to vote today. He said he lost his right to vote about 14 years ago for a felony charge of driving with a suspended license. He most regrets not getting to be a part of the historic 2008 election of Barack Obama. pic.twitter.com/OPblgrdcdo

— Andrew Pantazi 🐘 (@apantazi) January 8, 2019

“Thousands of people are registering to vote today,” Volz said. “It’s a real acknowledgement of the sacredness of democracy that’s happening in front of our eyes.”

Some top Republican officials in Florida, however, have sought to delay the implementation of Amendment 4. New GOP Gov. Ron DeSantis, who officially took office on Tuesday, said in December that the Florida Legislature, which does not convene until March, should pass “implementing language” before Amendment 4 took effect. Voting rights groups countered that the amendment was “self-executing” and “the Legislature does not need to pass implementing legislation in order for the amendment to go into effect.” Though new registrants are being processed today, the Legislature could still make the implementation of the law more restrictive when it convenes in the spring.

Paul Lux, president of the Florida State Association of Supervisors of Elections, told me that election officials in Florida had received no guidance from the state on how to comply with Amendment 4. “What we’ve heard is nothing,” he said. He said county supervisors, who oversee voter registration, would register new voters as required by the new law. “I am not aware of any supervisors who have said they won’t take registration forms,” Lux said. Meade and Volz said they were not aware of anyone being turned away from registering. “They were letting people register and celebrating with us,” Meade said of election officials.

Craig Aiken, 43, who did time for drug possession, registered to vote in Jacksonville Tuesday. “A second chance to be human,” he said of Amendment 4, which Florida voters approved in November pic.twitter.com/FS7Ef030Ce

— Steve Bousquet (@stevebousquet) January 8, 2019

Meade invited DeSantis to celebrate with returning citizens (his preferred term for ex-felons) who were registering today, noting that over 1 million DeSantis supporters also voted for Amendment 4. “We have a governor who campaigned on abiding by the rule of law, and this is the law now,” he said.

North Port resident Alan Rhyelle is the first convicted felon to register to vote under Amendment 4 in Sarasota County. He was waiting in the parking lot by 7:15 a.m.. Busted for growing pot to help his daughter struggling with prescription meds after car accident. pic.twitter.com/SDqrvPJhCk

— Zac Anderson (@zacjanderson) January 8, 2019

Meade told me that election officials in Orlando were crying as returning citizens registered for the first time in decades, some for the first time in their lives. “When I walked in there, there was a newfound appreciation for the right to vote,” he said. “We hope that’s a message we’re able to convey to other American citizens. There’s something beautiful about participating in American democracy. This is what democracy is all about—the more the merrier.”