President Donald Trump greets US Army Chief of Staff Mark Milley during a Rose Garden event with the Army football team.Alex Wong/Getty Images

The Army just released an 11-page blueprint for the next decade, providing in equal measure a frank look at the immediate priorities of the military’s largest fighting force and another reminder that graphic design is not necessarily a military specialty.

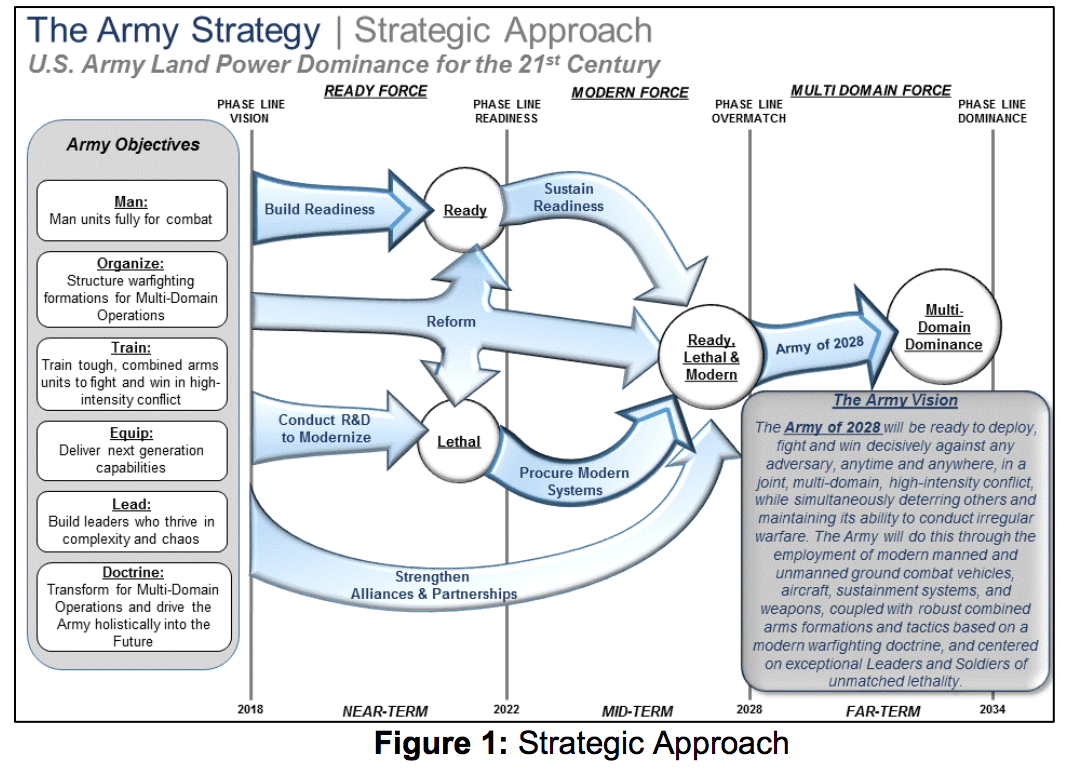

Let’s start with the centerpiece of the document—an ungainly mess of arrows and text boxes:

For a document that demands some careful reading and—on close inspection—offers some interesting insights into where the Army intends to deploy its resources, this reaction is probably not what the world’s largest military was hoping for online:

I turned the Army’s strategy slide into an illustration of an alien. pic.twitter.com/DFGM5JNhLO

— Lauren Katzenberg (@Lkatzenberg) October 25, 2018

This Army strategy for the next ~30 years doesn't look so good pic.twitter.com/Qc18Qekl97

— Kelsey D. Atherton (@AthertonKD) October 25, 2018

The aesthetic shortcomings aside, here are some of the major takeaways from the next decade of Army planning:

At least one part of Trump’s government still loves the global order

To hear Donald Trump tell it, America’s traditional allies like Canada and Germany are “dishonest and weak,” the 18-year war in Afghanistan has been a “total disaster,” and Kim Jong Un—in addition to being the dictator of one of the world’s most repressive regimes—is “very talented” and writes “beautiful letters.”

Against this geopolitical backdrop, here’s how the Army described the role of the United States in the world:

As the backbone of the international world order following World War II, the United States helped develop international institutions to provide stability and security, which enabled states to recover and grow their economies. Global competitors are now building alternative economic and security institutions to expand their spheres of influence, making international institutions an area of competition. As a result, we must strengthen our alliances and partnerships, and seek new partners to maintain our competitive advantage.

These “alternative economic and security institutions,” a nod perhaps to China and Russia’s growing influence in Eastern Europe and Asia, have flourished in no small part because of Trump’s retreat from global partnerships. “On his third day in office, [Trump] withdrew from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a twelve-nation trade deal designed by the United States as a counterweight to a rising China,” the New Yorker reported earlier this year. “To allies in Asia, the withdrawal damaged America’s credibility.”

Despite Trump’s “America first” rhetoric, Secretary of Defense James Mattis has mostly attempted to reassure our allies of our commitment to global cooperation during several trips abroad. Last June, he assured allies during a conference of defense ministers in Singapore that “we have got plenty of valid reasons for many nations to work together in maintaining the rules based order today,” including “the value in commerce and in security where we work together.” Mattis slightly altered his tone at this summer’s conference, when he spoke of taking “a clear-eyed view of the strategic environment” and recognizing “that competition among nations not only persists in the 21st-century, in some regard it is intensifying.” Put simply, the Army’s genial approach to our traditional allies is in stark contrast to Trump’s zero-sum view of foreign affairs.

A budget showdown is coming

Even as the Army strategy promotes “fiscal reforms to improve business processes,” its range of equipment upgrades and bulked-up recruiting will run at loggerheads with Trump’s stated priorities and a vexing appropriations process. Early in his term, Trump promised to build up the military’s fighting force, but this week he reportedly informed the Pentagon of his desire to cut $33 billion from next year’s budget proposal, Deputy Defense Secretary Patrick Shanahan said Friday.

The cut would align DoD with the other federal agencies Trump has asked to cut 5 percent from their budgets as part of his self-described “nickel plan.”

The Army acknowledges this uncertainty in its plan, stating, “fiscal uncertainty and decreased buying power will likely be a future reality, threatening our ability to achieve the Army Vision.” Defense spending bills have been a rare bipartisan affair in the past, but the makeup of the next Congress could explode that fragile consensus.

Mental health remains a distant priority

Since the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq began, the suicide rate among soldiers more than doubled. No shortage of reports and statistics exist—including many commissioned by the Army—on the problem of preventing suicide among active-duty and reserve members of the force. Suicide has become a leading cause of death for US service members—more than deaths caused by the Islamic State in some months.

Despite a widening focus across the services on the root causes of suicide and an acknowledged need for better treatment, intervention, and resilience, the strategic plan contains no references to suicide or mental health. Resilience is mentioned just twice and only to affirm that the Army’s force posture should be “lethal, agile, and resilient.”