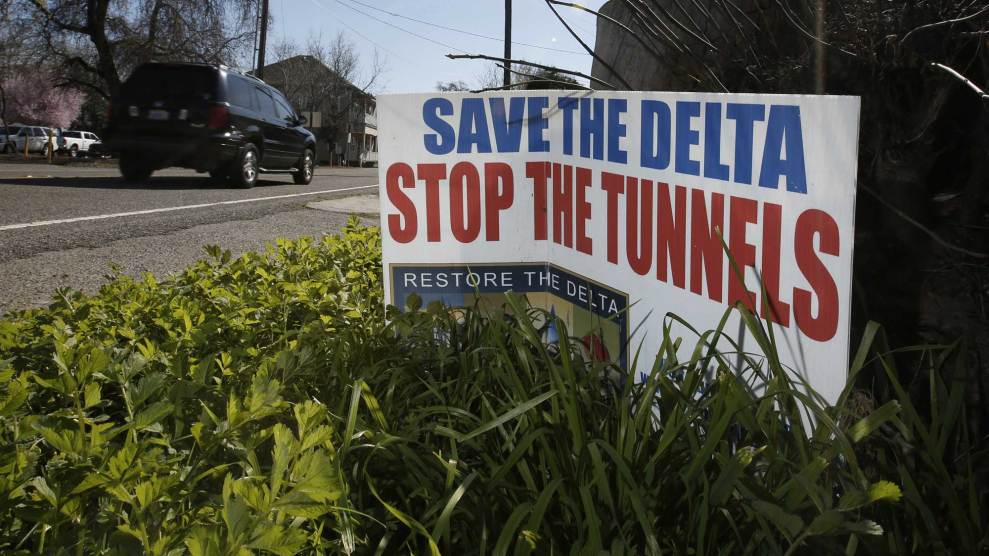

Rich Pedroncelli/AP

Over the strong objections of environmental groups and concerns raised by some of their own scientists, federal wildlife agencies on Monday approved the construction of $15 billion set of tunnels that will on average divert 20 percent of California’s ecologically sensitive Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers to Southern California cities and farms. “It’s farcical,” said Barbara Barrigan-Parrilla, the director of Restore the Delta, a group that represents environmentalists, fishermen, and farmers in the Sacramento Delta region east of San Francisco. “It’s an insult to the people who have tracked these projects all these years because we remember the science that has been performed.”

The tunnel project, known as California WaterFix, is designed to replace two huge pumps that have been blamed for sucking up and killing Delta smelt, a federally protected species that was once a major food source for Northern California’s dwindling salmon population. In 1993, the US Fish and Wildlife Service listed the smelt as “threatened” under the Endangered Species Act, setting the stage for severe limits on the pumping during California’s recent drought. The twin, 40-foot-wide, 35-mile-long tunnels, which will be permitted to carry up to 67,000 gallons of water per second, have been marketed by California Gov. Jerry Brown as a way to guarantee Southern California a more reliable water supply while also saving the smelt by diverting water further upstream in the Delta.

But environmental groups have adamantly opposed the plan based on concerns that the massive tunnels will cause more salt water to intrude into the Delta—a position that the Environmental Protection Agency agreed with as recently as January. California’s own 2015 environmental impact study of the project “continues to predict that water quality for municipal, agricultural, and aquatic life beneficial uses will be degraded and exceed standards as the western delta becomes more saline,” the EPA wrote early this year in a memo to state regulators. The memo predicted “substantial declines in quantity and quality of aquatic habitat for 15 of 18 fishes evaluated under WaterFix.”

The Trump administration’s decision to approve the tunnels is based on supportive biological opinions issued on Monday by the US Fish and Wildlife and National Marine Fisheries Services—though many details in the opinions raise red flags. The FWS biological opinion admits that “overall habitat conditions are not improved” by the tunnels project “compared to baseline conditions.” The NMFS opinion predicts the survival of many salmon runs through the delta will be substantially decreased, and that the abundance of winter run Chinook salmon will be lower than it is today.

A spokesman for the US Fish and Wildlife Service told me that such concerns will be addressed by a requirement that the tunnels project adhere to a set of eight “guiding principles,” including restoring and improving fish spawning habitat and feeding areas, reducing invasive species, and managing sediment. A major factor in the approval of the plan was a commitment by the state of California to restore 1,800 acres of prime fish habitat, said Paul Souza, the Pacific Southwest director of the US Fish and Wildlife Service. “We have concluded that WaterFix will not jeopardize endangered or threatened species or adversely modify their critical habitat,” he said in a phone conference with reporters on Monday.

Yet environmental groups remain unimpressed. The opinion is short on specifics on how the guiding principles will be followed, notes Doug Obegi, a staff attorney with the Natural Resources Defense Council’s water program, but instead “kicks the can down the road for someone else to magically solve.” And the 1,800 acres of restored habitat is a drop in the bucket compared with the 150,000 acres of restoration work that the original tunnels project had pondered (though the original plan also called for even more water diversions).

“It is inexplicable that the agencies would approve a project that is worse for salmon and native fish and wildlife in the Delta than the degraded status quo,” Obegi said. “Very disappointing, but the fight is far from over.”

Environmental groups are also concerned that while the tunnels will be permitted to carry just 67,000 gallons of water per second, they will have the capacity to carry up to 112,000 gallons per second. There are laws on the books to prevent that from happening, but Central Valley farmers are working diligently to overturn those laws. In December, for instance, Congress passed a rider in a federal water bill that allows officials at state and federal water management agencies to exceed the environmental pumping limits to capture more water during storms. “They really are trying to sacrifice one region for another,” Barrigan-Parrilla told me at the time. “If these plans come to pass, [the tunnels] are a complete existential threat to our communities, our people, and to the environment.”

As I reported last year, the California WaterFix is closely tied to billionaire almond and pistachio farmers Stewart and Lynda Resnick. In 2014, their employees quietly began conducting polling and focus groups to figure out the best way to sell the tunnels plan to skeptical voters. Months later they launched Californians for Water Security, a coalition of business and labor interests that promotes the tunnels as an earthquake safety measure. “An earthquake strikes a vulnerable place—the heart of California’s water distribution system,” cautions the group’s television ad. “Despite expert warnings, crumbling water infrastructure has not been fixed…Aqueducts fail. Millions lose access to drinking water…Our water doesn’t have to be at risk! Support the plan. Fix the system.”

Three weeks after the ad went live, Gov. Brown held a press conference in which he rebranded his plan as the California WaterFix.

The tunnels plan still remains far from a fait accompli. Some of the farmers and urban water users that would pay for the project have balked at its high cost, preferring instead to explore options such as rainwater capture. And federal agencies still have not approved an operations plan for the tunnels.

“We are preparing to fight this,” Barrigan-Parrilla says. “I just do not believe that cherry-picked science is going to stand up well in the courts, and I do not believe that the public is going to go along with paying for the project.”

This story has been updated.