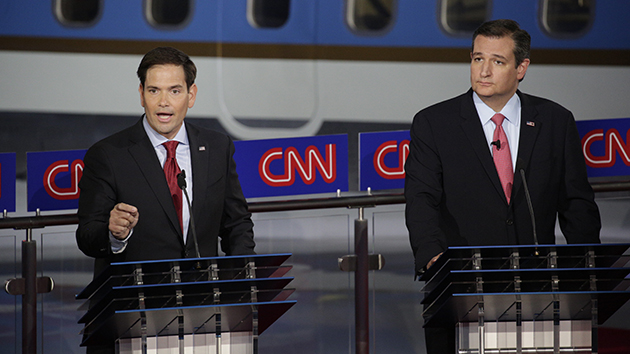

AP

Earlier this month, when Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.) named his top campaign representatives across Florida, he tapped a conservative activist named Clyde Fabretti as one of the leaders of his presidential effort in Orange County, a key district that includes Orlando. But Fabretti, the co-founder of the West Orlando Tea Party, has a sketchy background that might not reflect well on Rubio’s campaign: He is a convicted white-collar criminal with a history of questionable business dealings and associations with fraudsters. Most recently, Fabretti’s name surfaced in an ongoing lawsuit by investors in a tea-party-related media startup who claim he played a role in a company that allegedly defrauded them. And records show that the 67-year-old activist may have committed voter fraud by registering to vote and casting ballots in Florida elections when his criminal record rendered him ineligible to do so.

In 1997, Fabretti pleaded guilty to a single federal felony count of conspiracy to commit income tax evasion, bank fraud, mail fraud, and failing to file tax returns. He was sentenced to 21 months in prison and three years of probation. He was also ordered to pay more than $200,000 in restitution.

According to the federal indictment, Fabretti used his then-wife Susan, who worked for him, to execute an elaborate scheme to defraud First Union Corporation, the banking giant that eventually merged with Wachovia and later Wells Fargo. Prosecutors charged that in 1990 Fabretti provided his wife with false documents inflating her income and assets, which she then used to obtain a loan to buy a five-bedroom, eight-bathroom mansion in Oakton, Virginia.

The indictment also charged that Fabretti attempted to hide his assets by putting them in his wife’s name and masked his income by using corporate accounts he controlled to pay his rent, child support from a previous marriage, and living expenses. Susan pleaded guilty to bank fraud and tax evasion charges and was sentenced to three months in prison. Fabretti received a far harsher punishment.

This isn’t the only episode from Fabretti’s past that’s omitted from his online biography, in which he describes himself as the “quintessential entrepreneur” who has run an ad agency, a graphic arts production company, a printing firm, a small chain of hardware stores, a travel agency, and a real estate sales outfit. He notes that he’s a Vietnam vet who served in the US Air Force Postal and Courier Service and that he’s worked as a conservative political strategist. He currently promotes himself as a business and marketing consultant who offers “Christian conservative political consulting services.”

What he doesn’t highlight is his track record of working with shady operators who have been put behind bars for their scams and schemes. In the 1970s, according to the Washington Post, Fabretti worked for a notorious stock swindler named Cortes Randell who had earlier been convicted of orchestrating what the paper called “one of the biggest stock frauds in the history of Wall Street.” After completing a stint in federal prison, Randell had started a pair of companies that arranged barter deals between businesses and individuals, and Fabretti joined one of these firms. In 1977, federal investigators and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) began probing Randell’s business dealings. While these investigations were ongoing, Randell was charged in connection with a separate business scheme. He was again convicted of stock fraud, along with the interstate transportation of stolen funds and defrauding the Veterans Administration. He was sentenced to seven years in prison.

Fabretti, who was not implicated in any of Randell’s misdeeds, told the Washington Post that he quit Randell’s barter operation in 1978, when he learned it was not making any money. He set up a similar company, National Commerce Exchange, with another former Randell employee. That company, according to the Post, would arrange trades of anything from bat guano to plumbing services, for a fee.

Around 1994, Fabretti started another company, ITEX USA, which worked with a publicly traded barter firm called ITEX. Fabretti’s firm marketed and negotiated ITEX barter deals. ITEX, though, turned out to be a largely fraudulent enterprise that engaged in bogus barter deals, many of them involving company founder Terry Neal and offshore entities he controlled.

In 1999, the SEC filed a fraud suit against ITEX. When the case settled a year later, Neal was forced to repay $2.3 million in ill-gotten gains. (Fabretti, who was already in prison by the time the ITEX scandal emerged, was not involved in the SEC lawsuit.) Neal later pleaded guilty to tax fraud in a separate case and was sentenced to five years in prison.

After completing his prison term, Fabretti went to work for a retirement planning group in northern Virginia and eventually moved to Florida. He declared his official residence in the state in February 2006, about three years after getting off probation, and he registered to vote as a Republican in Florida that same month. The Orange County, Florida, voter registration form requires applicants to swear that they’ve never been convicted of a felony or, if they have, that they’ve had their voting rights restored by the governor. Lying on the form is a third-degree felony that carries a possible five-year prison term. The Florida Commission on Offender Review has no record of Fabretti getting his voting rights restored in the state, nor does Virginia, where Fabretti had lived previously. Nevertheless, Florida records show he voted in elections in 2006, 2008, 2010, and 2012.

In an email to Mother Jones, Fabretti did not respond to specific questions about his past record as a businessman or whether his voting rights had been restored, but he noted, “I have lived a very long life, and like many among us, I have accomplished much, done my share of good deeds, and have made my share of mistakes, for which I accept accountability. Some of the assertions about my life that it appears will be part of your article are true, some are misleading at best, and some are just blatantly false.” He did not respond to a follow-up email asking which details about his past he believed were misleading or “blatantly false.”

Fabretti’s involvement in Florida politics seems to have begun with the rise of the tea party movement. Ron McCoy, who started the West Orlando Tea Party, says Fabretti called him one day out of the blue after reading a newspaper article in which McCoy discussed establishing the tea party group. Fabretti told McCoy that he had been thinking about starting his own outfit, and the pair ultimately teamed up to run the West Orlando Tea Party. By 2011, Fabretti had become prominent on the local tea party scene and was appearing regularly in the media as a conservative activist representing central Florida tea party groups. During a 2011 political debate, he quizzed Florida state Senate candidates about their stance on a favorite tea party bugaboo—Agenda 21, the UN sustainable development initiative that Fabretti claimed was threatening the “sovereignty of America and the sanctity of our individual property rights.”

In 2011, Fabretti became a consultant to a new conservative media startup, Big Voices Media, founded by Billie Tucker, a prominent Florida tea party leader. The following year, several conservative activists who had invested tens of thousands of dollars in that endeavor sued Tucker and BVM, alleging that they illegally sold unregistered securities (that is, ownership stakes in the company) in violation of state and federal law and had misled investors. Fabretti is not a party to the suit. But in court filings, the investors have accused Fabretti of being involved in a scheme that caused them to lose more than $100,000.

Emails between Fabretti and Tucker—obtained by the plaintiffs during discovery—support the allegation that Fabretti played a behind-the-scenes role in the company. The plaintiffs claims they were unaware of Fabretti’s involvement in the firm when they first invested and that initially they did not know about his criminal record, which they only discovered later. The lawsuit is ongoing. Tucker, who declined to comment on the litigation, said through her lawyer that she was no long working with Fabretti.

Even before joining Rubio’s presidential campaign, Fabretti was helping the senator. When conservative activists assailed Rubio for seeking an immigration reform compromise, Fabretti defended him. “Whenever you hear he’s losing face with conservatives, that’s bunk,” he told the Tampa Bay Tribune in 2013. “The real grass roots tea party movement, the boots on the ground, we support his leadership.”

In April, a week before Rubio formally announced his White House bid, Fabretti attended a backyard party where the candidate informed some of his closest aides, donors, and supporters that he planned to seek the presidency. Fabretti says he was not invited but was brought to the event as a guest of someone who was “so that my 10 year old daughter could see Marco Rubio in person. Our exposure to Mr. Rubio at that time lasted a couple of minutes, we shook hands with Mr. Rubio, said hello and we never spoke to him again for the entire evening.”

Earlier this month, when the co-chair of Rubio’s Florida campaign announced the appointment of Fabretti and others to the candidate’s leadership team, he noted that “these grassroots leaders” were largely “new to the political arena.” If Rubio hopes Fabretti will rally anti-establishment tea party types for his presidential bid, he might be disappointed. The West Orlando Tea Party has gone dormant. The group hasn’t convened for more than a year, says McCoy, who’s no long involved with the outfit. Its corporate registration has been dissolved, and its website doesn’t appear to have been updated since 2013.

In his email to Mother Jones, Fabretti noted, “Like thousands of other unpaid grassroots supporters, I am and always have been, since Marco Rubio ran for Senate, an unpaid grassroots volunteer. Nothing more, nothing less. I am not now nor have I ever been a member of the Rubio Campaign staff… I am one of 6 other unpaid grassroots volunteers in Orange County, called ‘team leaders’ (there are almost 150 such unpaid grassroots volunteers called ‘team leaders’ in 67 Florida counties) whose only authority and responsibility, like mine, is to find other unpaid volunteers, like us, who are willing to make calls to voters, walk precincts and put Rubio For President signs in their yards. These ‘team leaders’ are such big shots that we have to pay $3 for a bumper sticker if we want one.”

The Rubio campaign did not respond to a request for comment.

One former business associate of Fabretti—who asked not to be identified—says he’s not surprised by Fabretti’s move into politics: “Fabretti is a natural-born promoter. A natural-born confidence man. It’s in his genes. He could sell anyone anything anytime.”