Tamir Rice's sister and mother at the park where the 12-year-old was gunned down.Michael McElroy/Zuma

At 3:22 p.m. last November 22, just minutes before 12-year-old Tamir Rice was fatally wounded by a Cleveland police officer at a neighborhood park, a man called 911 to report “a guy in here with a pistol…pointing it at everybody.” During the two-minute conversation, the caller described a person in a gray coat, “probably a juvenile,” who was sitting on a swing and holding a gun that was “probably fake.” Before hanging up, the caller reiterated his uncertainty about the gun: “I don’t know if it’s real or not.”

Those presumably important details would never go past that call.

Constance Hollinger, a Cleveland police dispatcher of 19 years, was on the other end of the line that day. Hollinger entered information from the caller’s description of the scene into the dispatch computer system, according to an official investigation of the case. A few minutes later, dispatcher Beth Mandl read Hollinger’s notes from a computer screen as she transmitted the information to police officers over the radio: “In the park by the youth center is a black male sitting on the swings. He is wearing a camouflage hat, a gray jacket with black sleeves. He keeps pulling a gun out of his pants and pointing it at people.”

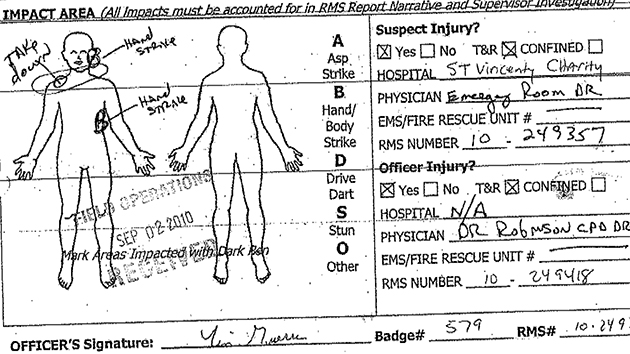

Mandl relayed it as a “code one,” indicating the highest priority level and the need for immediate response. By 3:30 p.m., officers Timothy Loehmann and Frank Garmback pulled up in front of Rice in the park, and within two seconds Loehmann jumped out and fired his gun at Rice at close range, striking him in the abdomen. For the next several minutes, Rice lay bleeding on the ground while the two officers stood by without giving him aid—inaction that may have potentially been criminal according to one policing expert—until other responders arrived, tended to Rice, and took him to a hospital, where he died the next day.

Recordings of the initial 911 call and the radio dispatch to officers, released by the Cleveland police department in November (listen below), showed that the details about Rice’s suspected age and fake gun never reached Loehmann and Garmback. After a five-month probe into the shooting by the Cuyahoga County Sheriff’s Department, which culminated in a 224-page report released in mid June, investigators concluded that these details did not make it from Hollinger to Mandl. The report did not specify why.

According to a county official familiar with the investigation who spoke to Mother Jones, the details were not relayed because Hollinger did not enter them into the dispatch computer system. Why she did not do so is one of several key questions still hanging over the case seven months later. The ongoing investigation is now in the hands of Cuyahoga County Prosecutor Timothy McGinty, who took over the case on June 3.

In an interview with Cuyahoga County sheriff’s detectives, Hollinger said that as a 911 call taker, she was responsible for retrieving “pertinent information” about each call—such as the caller’s name, address, location, and reason for the call—and assigning the call a priority level. But Hollinger refused to answer investigators’ questions about why she did not input the details about Rice’s suspected age and possibly fake gun, per the advice of her union-provided attorney.

Hollinger declined to comment to Mother Jones about her role in the case, citing the ongoing investigation and the Cleveland police department’s “stringent rules” about making public statements. Her attorney, Keith Wolgamuth, told Mother Jones that Hollinger “was advised to exercise her Fifth Amendment rights,” and that her actions last November 22 were within protocol. Wolgamuth, who says he has represented police radio dispatchers in Cleveland for 30 years, said “a prudent call taker” views information about a possible fake gun “as immaterial to the necessary police response because any gun could be fake, as the responding officers know.” As for the caller’s comments about Rice’s probable youth, he said, “the person could always be a ‘juvenile’ and, perhaps as importantly, there are plenty of juveniles that have real guns and use them, as police officers well know. A prudent call taker understands this information is not essential to the police response.”

[Listen to excerpts from the 911 call and the dispatch to officers:]

Experts on police dispatch operations declined to comment specifically on Hollinger’s handling of the 911 call. Speaking about industry best practices, they concurred that details about a juvenile or a possible fake gun would be important to relay to officers, both for their safety and tactical response.

Dave Warner, a former police officer who is a consultant for the International Academies of Emergency Dispatch, said a call reporting an armed suspect should prompt call takers and dispatchers to ask a series of questions—covering the suspect’s estimated age, whether medical assistance is required, whether the caller feels like he or she is in danger, and a description of the weapon. “If the caller says he thinks that it could possibly be fake, that should have been in there,” he said.

Warner pointed out, however, that even if Hollinger had relayed the missing details about Rice, there’s no way to know whether Loehmann and Garmback would have approached the scene differently or whether the fatal shooting would have been averted.

The precise level of detail required from a dispatcher depends on the police agency’s policies, notes Chris Carver, an operations director at the National Emergency Number Association. “There is an unbelievable amount of variance” across agencies on how to handle 911 calls, Carver says, adding that there’s no national standard on training for 911 personnel. “That is a critical issue we’re trying to address all around the country.”

In Cleveland, however, dispatchers are supposed to “relay all information included in an incident” to officers responding to a call, including a suspect’s “physical characteristics” and a weapon type and description, according to the agency’s policy for answering 911 calls.

“There is always the chance the witness is wrong, that the suspect has a real gun,” acknowledges Seth Stoughton, a former police officer who now teaches at the University of South Carolina School of Law. “But a witness’s description of a weapon as ‘probably fake,’ combined with a description of the suspect as a juvenile, is very different than a description of an adult holding a firearm that the witness is sure is real,” he says. “Officers may take a very different approach” to each of those cases, he says.

According to the 224-page report, Hollinger and Mandl worked in the same “large room” housing multiple dispatch operations. In an interview with Cuyahoga County sheriff’s investigators, Mandl said the only information known to dispatchers was what was entered into the dispatch computer system. Dispatchers have no other means to acquire information about a call, she said, and they have no direct contact with the caller, except in cases when an officer in the field requests additional information. There was no such request from Loehmann or Garmback on November 22 after Mandl broadcast the information from Hollinger.

According to a personnel file released by the city of Cleveland, a supervisor gave Hollinger a “satisfactory” performance rating in 2013, noting that Hollinger “tends to be abrupt, and disconnect the caller when they are attempting to provide additional info.”

The investigation by the Cuyahoga County Sheriff’s Department did not include any testimony from Loehmann and Garmback, who declined investigators’ repeated requests for interviews based on the advice of their union-provided attorneys. In an email to Mother Jones, Michael Maloney, an attorney representing the officers, said his clients also would not agree to an interview at this time with McGinty, the Cuyahoga County prosecutor. Maloney said his clients “have not ruled out the possibility of prepared written statements” for the prosecutor, and that they would make a decision about testifying before a grand jury “when the time comes.”

McGinty’s office declined to comment to Mother Jones about the case, including with regard to how much longer the investigation might take.