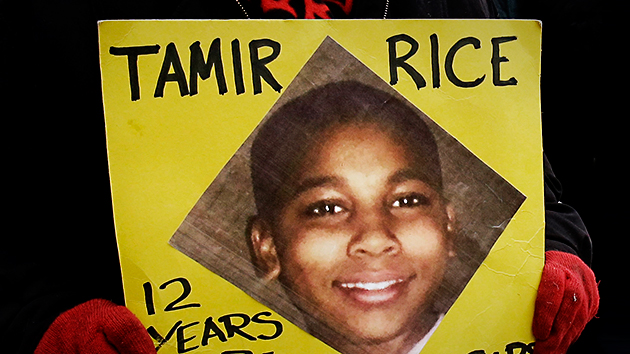

Tony Dejak/AP

When the Cuyahoga County Sheriff’s Department made its first public comments on Tuesday about its ongoing investigation into the death last November of 12-year-old Tamir Rice, it provided few details. Nearly six months since Cleveland police fatally shot Rice at a community center park where he had been waving around a toy gun, questions are mounting as to why the investigation has taken so long, especially given explicit surveillance footage of the shooting and the troubling police record of the officer who pulled the trigger.

Mother Jones has learned that the two officers involved in the shooting—Timothy Loehmann, who fired the shots, and Frank Garmback, who drove the police car—still have not been interviewed by investigators from the sheriff’s department. According to an official familiar with the case, investigators have made more than one attempt to interview Loehmann and Garmback since the Cleveland Police Department handed over the case in January. (Read more about why the sheriff’s department took over the investigation here.)

A county official familiar with the case told Mother Jones that the criminal investigation is focused solely on Loehmann. Garmback, who pulled the police car to within a few feet of Rice right before Loehmann stepped out and shot Rice almost instantly, is currently not under criminal investigation by the sheriff’s department, the official said.

In the surveillance footage, both Loehmann and Garmback can be seen standing around after the shooting while Rice lies bleeding on the ground. About a minute and a half after the shooting, Garmback can be seen tackling Rice’s 14-year-old sister as she tries to run to her wounded brother. Four minutes go by during which Loehmann and Garmback make no attempt to give Rice first aid. An FBI agent in the area then comes to the scene and begins to tend to Rice before an ambulance arrives to take him to the hospital (where he died the next day).

Michael P. Maloney and Henry Hilow, the two attorneys representing the officers, declined to comment to Mother Jones about the officers’ participation in the investigation, saying it would be inappropriate to do so while the investigation was ongoing.

Whether Garmback could also potentially face criminal charges is a complex question, says Seth Stoughton, a law professor at the University of South Carolina who studies policing. Stoughton says that he would expect prosecutors to at least consider the possibility, adding that both officers’ actions in the wake of the shooting also raise stark ethical questions: “The Tamir Rice shooting was a use of horrible tactics,” he says. “It was a ludicrous way to approach a scene where you’ve been told that there is a person with a gun who has been aiming it at bystanders. I would expect the officers would park at a safe distance and walk up, using cover and concealment, and try to initiate communication at a distance. That’s the ‘three Cs’ of tactical response.”

It remains unclear why, in the minutes after both Rice and his sister lay on the ground, the officers did not tend to Rice. According to Stoughton—who previously served as a police officer himself for five years—a fundamental principle of policing is that once a threat has been eliminated and a scene secured, an officer’s first priority is to aid an injured person. “At that point, the officer and his medical kit might be the only thing between the suspect and death,” he says. “It’s not only an ethical requirement but almost certainly a departmental imperative to do what they can to save the life of the suspect. The failure to do that is really disturbing.”

In Stoughton’s opinion, such inaction could potentially rise to the level of criminal charges, depending on departmental policy, state law, and other circumstances. He adds: “There’s nothing in the video suggesting that there was a threat that would justify the officers in doing anything other than rendering aid to Tamir Rice.”

In the statement to reporters on Tuesday, Cuyuhoga County Sheriff Clifford Pinkney said that his investigators had examined “thousands of pages of documents” and that “a majority of our work is complete.” According to an official familiar with the investigation, those documents include Rice’s autopsy report, a 911 call transcript, cellphone records, transcripts of interviews with witnesses, and the training records of both police officers.

The documents also include Loehmann’s mental-health records, as well as disciplinary records from both the Cleveland Police Department and the Independence Police Department, where he’d served until December 2012. A deputy chief’s letter from Loehmann’s personnel file there said that during firearms qualification training Loehmann was “distracted” and “weepy,” according to a report on Cleveland.com. It also said that Loehmann “could not follow simple directions, could not communicate clear thoughts nor recollections, and his handgun performance was dismal.”

The sheriff’s investigation is expected to conclude in the coming weeks, an official familiar with the work confirmed. In the meantime, Rice’s grieving family members felt they could no longer wait for closure. They’d been paying to preserve the boy’s body, the Washington Post reported on Wednesday, waiting until the legal investigation was complete, in case an additional medical examination was needed. Late last week the family decided to cremate Rice, the family’s attorney told the Post. “What everyone needs to understand is that Samaria Rice is a mother first,” the attorney said. “Whether in life or death, her instinct is to take care of her child. Him not being put to final rest was just physically, emotionally, psychologically unsettling to her.”