chapters

IT WAS A MILD, crystal clear desert evening on November 15, 2004, when Jennifer Longdon and her fiance, David Rueckert, closed up his martial-arts studio and headed out to grab some carnitas tortas from a nearby taqueria. They were joking and chatting about wedding plans—the local Japanese garden seemed perfect—as Rueckert turned their pickup into the parking lot of a strip mall in suburban north Phoenix. A red truck with oversize tires and tinted windows sideswiped theirs, and as they stopped to get out, Rueckert’s window exploded. He told Longdon to get down and reached for the handgun he had inside a cooler on the cab floor. As he threw the truck into gear, there were two more shots. His words turned to gibberish and he slumped forward, his foot on the gas. A bullet hit Longdon’s back like a bolt of lightning, her whole body a live wire as they accelerated toward the row of palm trees in the concrete divider.

The air bag against her was stifling, the inside of the cab hot. She managed to call 911. “Where are you shot on your body?” the dispatcher asked. “I don’t know, I cannot move. I can’t breathe anymore. Somebody help me,” she pleaded. “I’m dying.”

There was a rush of cool air, and a man leaning over her. Then a flood of bright lights. “Am I being medevacked?” she asked. “Those are news vultures,” the EMT told her. He shielded her face with his hand as they rushed the gurney into the ambulance. She couldn’t stop thinking of her 12-year-old. “Tell my son I love him,” she said.

Half of her ribs were shattered. Her lungs had collapsed and were filling with blood. As the ambulance screamed toward the hospital, Longdon, an avid scuba diver, clawed at the oxygen mask. She kept trying to tell them: “My regulator isn’t working. My regulator isn’t working.” The EMT held her hand as she faded in and out.

She was barely hanging on as the ER doctor prepared to insert a tube through her rib cage. “I’m really fast,” he assured her, “and I’m going to do this as quickly as I can.” As the nursing staff held her down, Longdon heard a dog wailing in the corner of the room. How could they allow a dog into this sterile place and let it howl like that? “The last thing I remember was realizing that it wasn’t a dog,” she recalls. “It was me.”

A couple of days into what would become her five-month hospital stay, Longdon was lying with her back to the door when a doctor came in. She didn’t see his face when he calmly told her the news: She was a T-4 paraplegic, no longer able to move her body from the middle of her chest down. Rueckert had also survived, but a bullet through his brain left him profoundly cognitively impaired and in need of permanent round-the-clock care.

Jennifer Longdon

for wheelchair-related modifications to her home

Antonius Wiriadjaja

for medical care, physical therapy, and counseling

Kamari Ridgle

for medical care, including a $25,000 medevac ride

Philip Russo

in lost household income

Pamela Bosley

in medical care and counseling for family

BJ Ayers

in state-funded emergency care

Caheri Gutierrez

for hospitalization and reconstructive surgeries

Paris Brown

for a year of grief counseling

Longdon didn’t know it yet, but she was also facing financial ruin. Shortly after the shooting, her health insurance provider found a way to drop her coverage based on a preexisting condition. She would be hospitalized three more times in quick succession, twice for infections and once for a broken bone; all told, the bills would approach $1 million in the first year alone. Longdon was forced to file for personal bankruptcy—a stinging humiliation for someone who had earned about $80,000 a year working in the software industry and building a massage therapy practice on the side.

“I’d never not paid a bill on time before that,” Longdon told me as we looked across the mostly empty parking lot on an overcast afternoon in late February. Little had changed about the place except for the name on the Mexican restaurant. “I felt like a failure,” she added, beginning the lengthy process of loading herself back into her custom lift-equipped van. “Those doctors had given their all to save my life.”

Over the past decade, Longdon has been hospitalized at least 20 times. One especially bad fall from her wheelchair in 2011 broke major bones in both legs. She came close to having them amputated and had to have titanium rods inserted. In 2013, she was admitted five times for sepsis, once after being defibrillated on her living room floor because the fever from the infection had caused her heart to stop. She has taken so many antibiotics that some no longer have any effect.

Most of Longdon’s medical bills have been covered through a combination of Medicaid and Medicare. Her income since the shooting has been primarily from Social Security Disability Insurance, which pays her about $2,000 a month. It has amounted to about a quarter million dollars over the past 10 years, though that’s barely been enough to keep her in her small house, which required extensive modifications just so she could wheel herself through the front door, take a shower, or make a bowl of ramen for dinner.

When I asked Longdon to try to add it all up—the hospital bills, the countless hours of physical therapy, the trauma counseling, the in-home care, the wheelchairs, the customized van, her lost income—she let out a sharp laugh. “Please don’t make me cry.” She pondered the numbers for a long moment. “I don’t know, maybe $5 million?” She started the engine and used a lever next to the steering wheel to accelerate back toward the main road.

How much does gun violence cost our country? It’s a question we’ve been looking into at Mother Jones ever since the 2012 mass shooting at a movie theater in Aurora, Colorado, left 58 wounded and 12 dead. How much care would the survivors and the victims’ families need? What would be the effects on the broader community, and how far out would those costs ripple? As we’ve continued to investigate gun violence, one of our more startling discoveries is that nobody really knows.

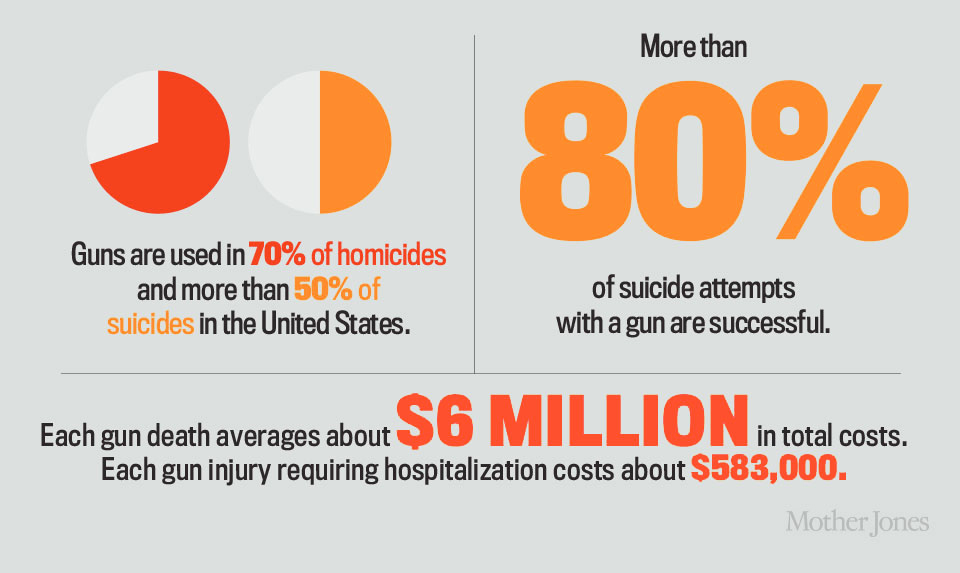

Jennifer Longdon was one of at least 750,000 Americans injured by gunshots over the last decade, and she was lucky not to be one of the more than 320,000 killed. Each year more than 11,000 people are murdered with a firearm, and more than 20,000 others commit suicide using one. Hundreds of children die annually in gun homicides, and each week seems to bring news of another toddler accidentally shooting himself or a sibling with an unsecured gun. And perhaps most disturbingly, even as violent crime overall has declined steadily in recent years, rates of gun injury and death are climbing (up 11 and 4 percent since 2011) and mass shootings have been on the rise.

Yet, there is no definitive assessment of the costs for victims, their families, their employers, and the rest of us—including the major sums associated with criminal justice, long-term health care, and security and prevention. Our media is saturated with gun carnage practically 24/7. So why is the question of what we all pay for it barely part of the conversation?

Nobody, save perhaps for the hardcore gun lobby, doubts that gun violence is a serious problem. In an editorial in the April 7 issue of Annals of Internal Medicine, a team of doctors wrote: “It does not matter whether we believe that guns kill people or that people kill people with guns—the result is the same: a public health crisis.”

And solving a crisis, as any expert will tell you, begins with data. That’s why the US government over the years has assessed the broad economic toll of a variety of major problems. Take motor vehicle crashes: Using statistical models to estimate a range of costs both tangible and more abstract—from property damage and traffic congestion to physical pain and lost quality of life—the Department of Transportation (DOT) published a 300-page study estimating the “total value of societal harm” from this problem in 2010 at $871 billion. Similar research has been produced by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) on the impact of air pollution, by the Department of Health and Human Services on the costs of domestic violence, and so on. But the government has mostly been mute on the economic toll of gun violence. HHS has assessed firearm-related hospitalizations, but its data is incomplete because some states don’t require hospitals to track gunshot injuries among the larger pool of patients treated for open wounds. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has also periodically made estimates using hospital data, but based on narrow sample sizes and covering only the medical and lost-work costs of gun victims.

Why the lack of solid data? A prime reason is that the National Rifle Association and other influential gun rights advocates have long pressured political leaders to shut down research related to firearms. The Annals of Internal Medicine editorial detailed this “suppression of science”:

Two years ago, we called on physicians to focus on the public health threat of guns. The profession’s relative silence was disturbing but in part explicable by our inability to study the problem. Political forces had effectively banned the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other scientific agencies from funding research on gun-related injury and death. The ban worked: A recent systematic review of studies evaluating access to guns and its association with suicide and homicide identified no relevant studies published since 2005.

An executive order in 2013 from President Obama sought to free up the CDC via a new budget, but the purse strings remain in the grip of Congress, many of whose members have seen their campaigns backed by six- and even seven-figure sums from the NRA. “Compounding the lack of research funding,” the doctors added, “is the fear among some researchers that studying guns will make them political targets and threaten their future funding even for unrelated topics.”

David Hemenway, director of the Harvard Injury Control Research Center, describes the chill this way: “There are so many big issues in the world, and the question is: Do you want to do gun research? Because you’re going to get attacked. No one is attacking us when we do heart disease.”

To begin to get a grasp on the economic toll, Mother Jones turned to Ted Miller at the Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation, an independent nonprofit that studies public health, education, and safety issues. Miller has been one of the few researchers to delve deeply into guns, going back to the late 1980s when he began analyzing societal costs from violence, injury, and substance abuse, as well as the savings from prevention. Most of his 30-plus years of research has been funded by government grants and contracts; his work on guns in recent years has either been tucked into broader projects or done on the side. “I never take positions on legislation,” he notes. “Instead, I provide numbers to inform decision making.”

Miller’s approach looks at two categories of costs. The first is direct: Every time a bullet hits somebody, expenses can include emergency services, police investigations, and long-term medical and mental-health care, as well as court and prison costs. About 87 percent of these costs fall on taxpayers. The second category consists of indirect costs: Factors here include lost income, losses to employers, and impact on quality of life, which Miller bases on amounts that juries award for pain and suffering to victims of wrongful injury and death.

In collaboration with Miller, Mother Jones crunched data from 2012 and found that the annual cost of gun violence in America exceeds $229 billion. Direct costs account for $8.6 billion—including long-term prison costs for people who commit assault and homicide using guns, which at $5.2 billion a year is the largest direct expense. Even before accounting for the more intangible costs of the violence, in other words, the average cost to taxpayers for a single gun homicide in America is nearly $400,000. And we pay for 32 of them every single day.

Indirect costs amount to at least $221 billion, about $169 billion of which comes from what researchers consider to be the impact on victims’ quality of life. Victims’ lost wages, which account for $49 billion annually, are the other major factor. Miller’s calculation for indirect costs, based on jury awards, values the average “statistical life” harmed by gun violence at about $6.2 million. That’s toward the lower end of the range for this analytical method, which is used widely by industry and government. (The EPA, for example, currently values a statistical life at $7.9 million, and the DOT uses $9.2 million.)

Our investigation also begins to illuminate the economic toll for individual states. Louisiana has the highest gun homicide rate in the nation, with costs per capita of more than $1,300. Wyoming has a small population but the highest overall rate of gun deaths—including the nation’s highest suicide rate—with costs working out to about $1,400 per resident. Among the four most populous states, the costs per capita in the gun rights strongholds of Florida and Texas outpace those in more strictly regulated California and New York. Hawaii and Massachusetts, with their relatively low gun ownership rates and tight gun laws, have the lowest gun death rates, and costs per capita roughly a fifth as much as those of the states that pay the most.

At $229 billion, the toll from gun violence would have been $47 billion more than Apple’s 2014 worldwide revenue and $88 billion more than what the US government budgeted for education that year. Divvied up among every man, woman, and child in the United States, it would work out to more than $700 per person.

But even the $229 billion figure ultimately doesn’t capture what gun violence costs us. For starters, there are gaps in what we know about long-term medical and disability expenses specifically from gunshots. Miller’s research accounts for about seven years of long-term care for victims, and for lifelong care for those with spinal-cord or traumatic brain injuries. But Kelly Bernado, a former police officer who now works as an ER nurse near Seattle, points out that survivors’ life spans and medical complications can exceed expectations. One of her patients was shot as a teenager: “He was paralyzed from the neck down and could not feed himself, toilet himself, dress himself, or turn over in bed. He will live the rest of his life in a nursing home, all paid for by the taxpayers, as he is a Medicaid patient.” She estimates that over the last two decades the price tag for this patient’s skilled nursing care alone has been upwards of $1.7 million. Even in less severe cases the consequences from gunshots can be profound, says Bernado, who joined the advocacy group Moms Demand Action for Gun Sense not long after police killed a man who had been firing shots outside her son’s high school. “These people have long-term problems—bowel issues, arthritis problems, chronic pain. They’re on pain medication, and there are addiction issues. They keep returning to the hospital.” In August 2014, a medical examiner concluded that former presidential aide James Brady’s death in a nursing home at age 73 was due to complications from the bullet he took to his head during the attempt on Ronald Reagan’s life almost 34 years earlier.

To gauge mental-health impact, Miller uses a study he coauthored back in 1998 that surveyed practitioners treating patients for trauma stemming from a broad range of violent crime. It calculated the rate of people who sought counseling, and the corresponding costs. Applying those numbers to current data on gun injuries and deaths gives an estimate of $410 million annually in direct mental-health costs. But that sum would rise substantially if all gun victims and their families could afford to seek counseling. Miller hasn’t had resources to build on the data since, and Mother Jones could find no other firearm-related mental-health studies by government or private institutions.

Then there are the costs that the available research doesn’t capture at all. What about the trauma to entire communities, whether from mass shootings or chronic street violence? What about the steep societal cost of fear, which stunts economic development and provokes major spending on security and prevention? “This is what big-city mayors worry about,” says Duke University economist Philip Cook, who coauthored a study 16 years ago that asked people how much they’d be willing to pay to reduce gun violence where they live. “How can Camden get out of the profound slump it’s in? The first answer has to be, ‘We’ve got to do something about the gun violence.'”

The fallout from mass shootings, which have been on the rise in recent years, includes outsize financial impact. Legal proceedings for the Aurora movie theater killer, for example, reached $5.5 million before the trial even got underway this spring, including expenses related to the pool of 9,000 prospective jurors called for the case. Most Americans probably don’t even recall a less lethal rampage that took place just a few months after the Aurora tragedy, at the Clackamas Town Center near Portland, Oregon. When a gunman killed two people, wounded another, and took his own life at the shopping complex in December 2012, more than 150 officers from at least 13 local, state, and federal law enforcement agencies responded—an investigation that lasted more than three months and culminated in a report nearly 1,000 pages long. To calm the public, make repairs, and beef up security, the 1.5-million-square-foot mall shut down for three days during the height of the holiday shopping season, depriving 188 retail businesses of revenue.

Since the mass shooting at Columbine High School in 1999, the federal government has doled out at least $811 million to help school districts hire security guards, including $45 million since 20 first-graders and six adults were massacred at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut. That sum doesn’t account for spending at the state and local level; according to the trade magazine Campus Safety, approximately 90 percent of American school systems have made security enhancements since Sandy Hook. Many have worked with law enforcement agencies to conduct active-shooter drills. Companies are marketing “bulletproof” backpacks and other defensive gear for children. A Massachusetts school recently tested an “active-shooter detection system” that costs as much as $100,000 and uses technology also deployed in war zones. One research company recently projected that by 2017, school security systems will be a $5-billion-a-year industry.

Jennifer Longdon knows how culturally important guns are in Arizona, where almost anyone 18 and older can purchase firearms at any time, no questions asked. She grew up with guns and has shot them for sport over the years, including periodically since her injury—she favors the reliable heft of a .45-caliber Glock in her palm.

She also sometimes worries that she might turn one on herself. She staves off the feeling with a packed schedule and the occasional pour of añejo. But grief, PTSD, and perpetual neuropathic pain linger. So do the questions.

Had they been targeted? Was it a spontaneous act of road rage? Maybe a case of mistaken identity? The Phoenix police investigated, but never arrested anyone.

Sitting near her favorite waterfall at the Japanese garden where she and Rueckert once planned to get married, Longdon tells me how she eventually had to let go of the idea of justice. “People think all of these crimes make sense,” she says, “that all of them have some beginning, middle, and end. They don’t.”

Longdon, who is 55 and has long dark hair and a sly, charismatic smile, never lets a conversation stay heavy for too long. Many days, she transports herself to meetings with advocacy groups, the mayor’s office, or Arizona legislators, hammering away on guns and disabilities issues alike. So you’d better not refer to her as handicapped or wheelchair-bound—she’s a woman and a wheeler. “I’m no saint,” she adds, “simply a deeply flawed loudmouth on a mission.”

Before her injury, fitness was essential to her life. She and Rueckert were black-belt martial artists and trained rigorously. Often they would begin their days by hiking to the top of Piestewa Peak, where they’d snack on fruit and watch the sun rise over the mountains around Phoenix.

Now, Longdon says, “my morning ritual is so consumed with just setting up this body for survival for the day.” It’s a taxing hour and a half: the careful process of checking her lower limbs and getting out of bed, the transfers to the toilet and then the shower chair—every day a formidable workout for the arms—and then the tedious process of “logrolling” into her clothes. “And that’s before I even put on my makeup, get the coffee going, and start thinking about work,” she says.

Gun politics in Arizona are as rough as anywhere, and on the morning we head over to Phoenix City Hall, Longdon is going off about legislation just introduced by a state senator to legalize silencers and sawed-off shotguns. Longdon believes in universal background checks for gun buyers, a position national polls show is shared by most gun owners. But speaking out about the issue has drawn her vicious attacks from gun rights activists—she’s been stalked, spat on in public, and harassed with rape and death threats.

Nobody who knows Longdon expects any of that to get in her way—certainly not the mayor’s chief of staff, Reuben Alonzo, who worked closely with her on a program in 2013 that took 2,000 unwanted firearms off the streets, the largest buyback in the state’s history. Longdon was one of the first people the mayor turned to for advice on gun policy, Alonzo says, noting that it wasn’t just a matter of her personal story. “There’s a stereotype about advocates like Jennifer,” he says, “but her approach is really quite pragmatic. She has the knowledge to back it up.”

Longdon is well aware that 2,000 unwanted guns melted down by the Phoenix PD is a tiny fraction of the firepower out there. But the cost of gun violence works out to more than $800 a year each for Arizona’s 6.7 million residents, and if she can start to chip away at that by keeping guns out of the wrong hands, it’s worth it to her. “Not one of those guns will ever be used in a suicide, an accidental discharge, or a crime,” she says, “and that is significant.”

And maybe it will help save someone from having to pay what she has. “There’s nothing I wouldn’t give to go back to where life was before. On long nights, when I’m alone and my pain level is high, and maybe something has triggered the memories, I have to be really careful not to let that melancholy and grief overwhelm me,” she says. “It’s an ongoing battle every day—choosing to stay alive, and to continue to fight.”