A health care worker in Freetown discharges a young patient from an Ebola treatment center.Jennifer Yang/ZUMA

With the death toll in the worst Ebola outbreak in history exceeding 1,000, pharmaceutical companies and health authorities are sprinting to develop new drugs and vaccines. On Monday, drug maker GlaxoSmithKline announced that it would start clinical trials of an Ebola vaccine ahead of schedule. And on Tuesday, the World Health Organization ruled that the use of experimental drugs to treat Ebola patients is ethical so long as the patients give their consent. But for now, there are no proven drugs to treat Ebola, and experts doubt that any new drug or vaccine could beat back the current outbreak in Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Guinea.

“The drugs are not going to stop the outbreak, period,” says Robert Garry, a virology researcher at Tulane University. One problem, he says, is the meager supply of drugs and vaccines. ZMapp, an experimental drug, has already begun human trials. But Mapp Biopharmaceutical, the company developing ZMapp with the help of the US Army, did not expect to start human tests this early, and it has only about a dozen doses. It has already sent two of those doses to Liberia.

Any Ebola vaccine, meanwhile, could not help contain the spread of the disease unless it is administered to huge numbers of people. GlaxoSmithKline, which is working on a vaccine in concert with the National Institutes of Health, has produced just a few hundred doses intended for future clinical trials, the company told the New York Times. In the best case scenario, the vaccine will go to market sometime next year.

When a new drug or vaccine does become available, Garry says, medical workers in West Africa will face difficulties reaching people in need. Mistrust of doctors has already hampered aid efforts in some hard-hit regions. “And we’re talking about areas where there virtually is no infrastructure,” he adds.

Ahmed Tejan-Sie, a North Carolina doctor who created a petition urging the FDA to speed up clinical trials of potential medicines, agrees that new drugs don’t have much potential to help the people who are currently affected. Stabilizing the drugs so that doses stay potent under tropical conditions with unreliable refrigeration, he notes, poses a particular problem.

Although new drugs probably won’t be able to stop the current crisis, Tejan-Sie, whose parents and sister live in Freetown, Sierra Leone, hopes that speedier drug development will help prepare the region for future outbreaks. That is the general hope of the medical community.

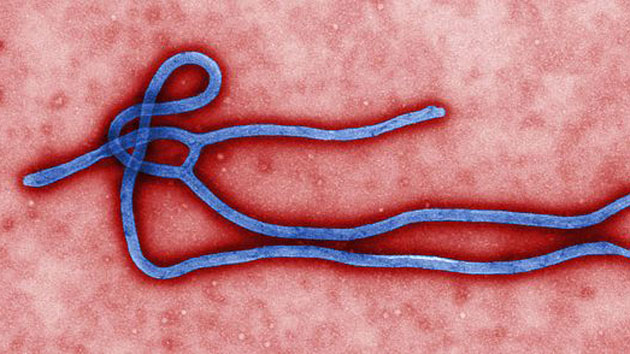

“Some of these drugs look great in the test tube and in mice and primates,” says Erica Saphire, a molecular biologist at Scripps Research Institute whose lab is studying the effectiveness of ZMapp. The drug is a cocktail of antibodies that attach to the virus or infected human cells, flagging them for destruction by the immune system and “locking” Ebola’s viral machinery so that the virus can no longer invade healthy cells.

Ebola usually kills humans within days. But trials on lab mice suggest that certain drugs in the pipeline could prolong the amount of time that doctors have to to save Ebola patients. In mice, Saphire says, “multiple days after [receiving] multiple times the lethal dose [of virus], many can be saved. Which is great. Because if a patient comes to your hospital, you don’t always know how long it’s been since they’ve been infected.”

The nature of Ebola may ultimately allow researchers to develop a drug that remains effective against the virus for years. Unlike other viruses, such as HIV, which can live in a patient for long periods of time, Ebola either kills its host or is eradicated by the immune system in a matter of weeks or even days. Ebola’s speed is part of what makes it so horrifying. But its short lifespan within a single human means the virus only interacts with any drugs a patient takes very briefly—and has limited opportunities to develop drug resistance.

ZMapp is not showing promise as a treatment for other strains of Ebola, such as Sudan ebolavirus, the type of Ebola that’s endemic in parts of East Africa. (None of those strains are at play in the current outbreak, which is limited to three countries in the West.) But researchers are preparing for future outbreaks of those strains, too. The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases has given Ebola researchers, including Saphire, $28 million over five years to combine and test therapies developed in labs as far-flung as Canada, Japan, and San Diego against the various strains of the virus.

Garry emphasizes that, while new drugs may not be key to stopping new cases of Ebola, they can still save lives. “For humanitarian reasons and for good patient care—and because it’s the right thing to do—we should give [these drugs] to as many people as we can,” Garry says. “The best we can hope, for drugs and vaccines in this particular outbreak, is that they give us some preliminary data,” Garry says. “Is this the best combination of drugs? Is this medication or that medication the best?”

There is one way new drugs could take on a larger role, Garry adds: If West African governments are unable to stop the spread of the current outbreak, and it continues to spread. “It’s scary to think about,” he says. “But we could still be talking about the ongoing Ebola outbreak a year, two years from now.”