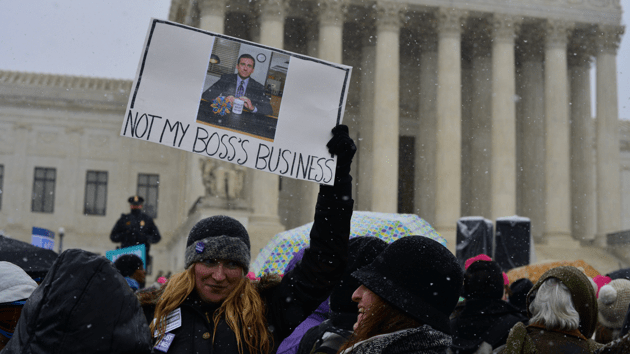

Jay Mallin/ZUMA

The Supreme Court on Monday blew a hole in an Obamacare provision that required employers to provide employees with contraceptive coverage. Specifically, companies whose owners have religious objections to covering contraception are now off the hook—regardless of whether their objections are based in reality.

So what does this mean for women who work for Hobby Lobby—or one of the 70 other companies that challenged Obamacare’s contraception mandate? The White House is considering whether President Obama can take unilateral action to ensure that they are covered. Health care experts say his administration can cover woman affected by today’s ruling similar to how it currently covers women working for nonprofit, religiously affiliated organizations.

Under the accommodation the federal government has worked out with religious nonprofits, the government waives fines for organizations that do not wish to cover contraception; the organization’s insurer or a third-party plan administrator provides the coverage instead. The cost is borne by the insurer, or in the latter case, the government.

“The obligation to provide [contraception] is technically on the insurers,” explains Timothy Jost, who runs Health Affairs Blog. “It’s just the government’s preference that the employers administer the coverage.”

Using the same workaround, the government can ensure that employees of companies such as Hobby Lobby still get the contraception coverage they are entitled to under the Affordable Care Act, says Sara Rosenbaum, chair of the health policy school at George Washington University. “The only difference is that the employer is not exposed to the cost,” she says.

Jost notes: “I don’t see any reason why [the Obama administration] couldn’t do it this way. The Supreme Court more or less told them to do it, or strongly suggested they do it.”

Indeed, the five justices who ruled in favor of Hobby Lobby made the accommodation a key piece of their decision. “HHS has…effectively exempted religious nonprofit organizations with religious objections to providing coverage for contraceptive services,” the court noted in its opinion. The justices suggested extending that exemption, which “does not impinge on the plaintiff’s religious beliefs.”

The cost of closing the coverage gap will fall to insurance companies, and in limited cases, the federal government. Jost estimates that most closely held companies, which tend to be small, are not self-insured. When one of those firms opts out, the cost of covering its employees’ contraceptives will fall to the company’s insurer. If a company that provides its own insurance declines to cover contraception, the company’s third-party plan administrator will offer contraception coverage. In compensation, the federal government will then waive some of the taxes the plan administrator would have paid to support the federal health care exchanges.

Rosenbaum says the existence of the religious nonprofit exemption, which has been upheld by several federal courts, helped doom the contraception mandate.

“There were very powerful arguments as to why corporations should not be allowed to put their employees’ benefits aside,” says Rosenbaum. “It’s a very unfortunate decision.” But, she adds, the government never made a convincing argument for why it couldn’t simply make the same accommodation for Hobby Lobby that it did for nonprofits such as the University of Notre Dame. “It was one of the weaknesses in the government’s arguments all along…and the Supreme Court seized on that.”