<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-110179493/stock-photo-explosion-of-nuclear-bomb-over-city.html?src=mhfbgpQ9C-ivI0Wq4dCGEg-2-130">Elena Schweitzer</a>/Shutterstock

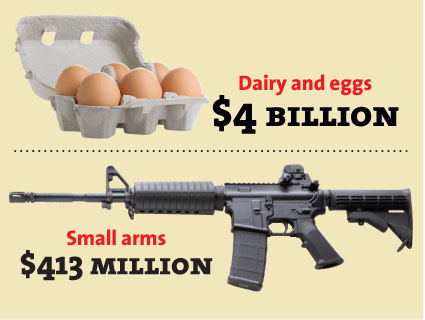

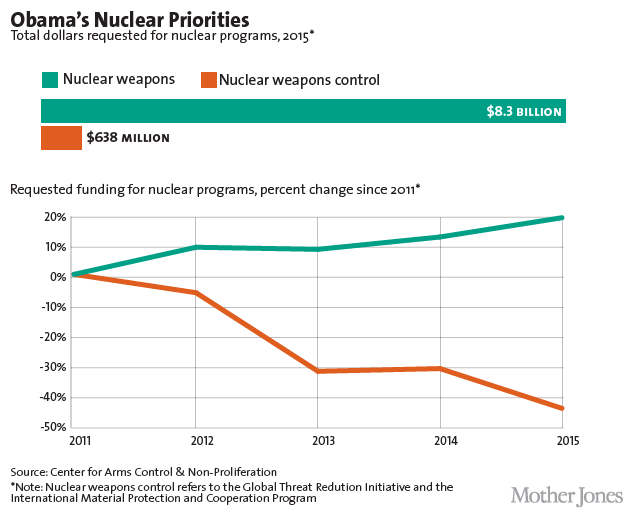

Last week, President Barack Obama claimed to be less worried about security threats from Russia than “the prospect of a nuclear weapon going off in Manhattan.” If that’s the case, however, it isn’t reflected in his latest military budget, which would boost funding for maintaining and developing atomic weapons while cutting back programs that help keep bomb-making materials out of the hands of terrorists.

“It’s troubling that for the third year in a row, the President’s budget proposal funds nuclear weapons programs at the expense of virtually every nonproliferation effort,” Rep. Mike Quigley (D-Ill.), who sits on the House Appropriations Committee, said in a statement provided by his aides. “Maintaining our existing nuclear weapons stockpile is already unsustainable, and it makes little sense to increase investments in weapons that matter less and less for our national security.”

The administration’s proposed 2015 budget reduces the National Nuclear Security Administration’s $790 million in spending on nuclear nonproliferation programs by 20 percent, or $152 million. The cuts apply to NNSA programs that secure buildings containing fissile material, prevent the smuggling of radioactive material across borders, and convert nuclear reactors to use low-enriched uranium, which, unlike highly enriched uranium, cannot be used in nuclear warheads.

At the same time, the Obama budget increases the NNSA’s spending on nuclear weapons systems by nearly 6 percent, or $445 million. This includes a $100 million increase for the “life extension” of the B61 nuclear gravity bomb, a Cold War-era weapon stationed mostly around Europe that many arms experts call outdated and unnecessary.

“It’s misplaced priorities across the board,” says James Lewis, communications director for the Center For Arms Control And Non-Proliferation. The nation’s nuclear weapons complex “is just such a massive behemoth that there really isn’t money for anything else.”

Energy Secretary Ernest Moniz has defended the cuts, albeit without much enthusiasm. “Nuclear nonproliferation programs, I’m afraid, is not such a great story,” he told the Albuquerque Journal News last month. “It’s frankly disappointing that we have such a substantial reduction this year. However, I do want to emphasize that this will continue to be a very robust program.”

Yet according to the Center For Arms Control, the cuts will hobble the NNSA’s primary nonproliferation efforts—the Global Threat Reduction Initiative and the International Materials Protection Cooperation Program, which focus on securing nuclear materials controlled by foreign governments. In particular, the cuts will delay by five years (until 2035) the conversion of 200 reactors away from using highly-enriched uranium, and likely will prevent the agency from securing 8,500 buildings containing radioactive material by its target date of 2044, which is already two decades past the date set two years ago.

In addition to the cuts detailed in the chart that accompanies this story, the NNSA plans to chop in half the $400 million budget for the Mixed Oxide fuels program, whose purpose is to dispose of the plutonium from dismantled nukes by modifying it for use in civilian reactors. Plagued with technical problems and cost overruns, the MOX program is now being put into “standby mode,” according to Moniz. Yet the NNSA has no alternative long-range plan for disposing of unwanted plutonium—or for channeling the cuts to MOX into other nonproliferation programs.

The arms experts I’ve spoken with are appalled by the administration’s lack of urgency about loose nukes. Hundreds of sites in 25 countries, taken together, contain some 2,000 metric tons of nuclear material, and much of it isn’t effectively secured. A team with the appropriate technical expertise and enough high-enriched uranium to fill a five-pound sugar bag, or a grapefruit-sized quantity of plutonium, could fabricate a devastating nuclear device. And while few people have the engineering skills to build and detonate a nuke, terrorists could still cause panic by exploding a non-nuclear “dirty bomb” that disperses these elements, contaminating a populated area.

Early last month, President Obama told Massachusetts political fundraiser Chris Gabrieli that “loose nukes” are the number one thing that keeps him up at night, Gabrieli told the Boston Radio station WBUR. But when I asked the DOE who within the administration had advocated for the cuts to nonproliferation, a spokesman declined to comment.