<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/whitehouse/8477041444/in/photostream">White House</a>/Flickr and <a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/60969081@N00/8292545493/sizes/l/">Gavroche_</a>/Flickr

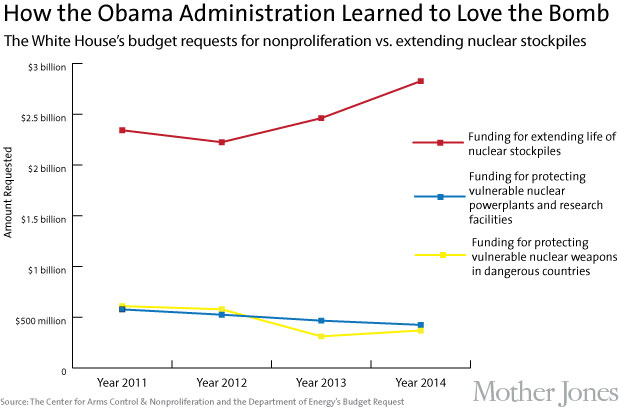

In the winter of 2012, President Obama stood on a podium at the National Defense University to honor the 20th anniversary of a program that successfully dismantled nuclear weapons in the former Soviet Union, declaring, “We simply cannot allow the 21st century to be darkened by the worst weapons of the 20th century.” He reaffirmed his commitment to continue investing in nonproliferation, because “our national security depends on it.” But his administration’s recently released budget proposal reflects the opposite agenda: It makes big cuts to nuclear nonproliferation programs while beefing up funding for the United States’ nuclear-weapons stockpile.

“I’m baffled as to why they would do that,” says Barry Watts, a senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, a national-security policy think tank, said of the Obama administration. “Nonproliferation goes straight to the heart of their policy.” Obama’s budget proposal for 2014 would cut $400 million from nonproliferation programs while spending an additional $560 million on extending the life of our atomic arsenal (compared to the fiscal 2012 budget).

Experts say the most consequential cuts to nonproliferation efforts in Obama’s budget—some $79 million—are slated to come from a program called the Global Threat Reduction Initiative. GTRI takes highly enriched uranium from other countries and sends it to the United States or Russia to be converted into non-weapons-grade material. The program also protects vulnerable nuclear materials at civilian energy and research sites around the world. Since 2009, GTRI has removed more than 3,000 pounds of highly enriched uranium and plutonium, enough to make dozens of nuclear weapons.

The Global Threat Reduction Initiative is a “core material security program to ensure that terrorists can’t their hands on nuclear weapons-usable material,” explains Kingston Reif, director of nonproliferation programs at the Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation. In 2012, the administration projected that it would spend $630 million on the GTRI in 2014. Obama’s current budget proposal requests $424 million. Obama’s 2013 budget proposal for GTRI was so low that Congress voted to increase funding by $35 million beyond the level that the administration requested. “We are hoping for the same thing this year,” Reif says.

Other nonproliferation programs are slated for cuts too. The Fissile Materials Disposition Program could see its budget cut from $685 million in 2012 to $502 million in 2014. The program tracks where fissile materials are going so they can’t be stolen or diverted and made into nuclear weapons.

The shift away from nonproliferation efforts, Reif says, is likely the result of austerity policies crimping the president’s agenda. Watts, of the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Studies, speculates that the thinking inside the White House “could have been: ‘We need to hack so much out of the discretionary spending budget,’ and nonproliferation took a hit.”

Yet the budget cuts are not across the board. Obama is not only proposing pouring more money into maintaining our nuclear stockpile—his administration is also putting about $1 billion into turning B61 nuclear bombs in Europe into weapons that can be delivered by F-35 fighter jets.

The nonproliferation advocates are baffled. At a 2009 speech in Prague and in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, Obama vowed to work toward a world free of nuclear weapons. The new budget is “inconsistent with the philosophy the president has espoused at Prague and in his Nobel Peace Prize speech. The direction seems wrong,” says Philip Coyle, a senior science fellow at the Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation and a former associate director of the White House Office on Science and Technology. Obama “committed to reducing the stockpile, and stockpiles are scheduled to go down. The DOD has supported that. The vice chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff has supported that. The Secretary of State has supported that.”

The renewed focus on maintaining the nuclear arsenal, says Watts, may reflect a shift away from the administration’s idealistic stance. Though Obama’s position has been to “try to get out of the nuclear business in the long run, the problem with that is if you look at virtually all other nuclear-powers wannabes, they don’t seem inclined to follow our lead, which I think was the hope.” Last week, a Chinese defense white paper appeared to alter the country’s long-standing commitment to not use its nuclear weapons first. Writing in the New York Times, James M. Acton of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace said this move “may also make it more difficult politically for President Obama to carry out his ambitious nuclear agenda.”

Coyle worries that the overall effect of the White House’s about-face on nuclear weapons policy could prove counterproductive. “We don’t want more nuclear weapons in the world,” he says. “We’re asking North Korea to stop its program. We’re asking Iran to stop its program. And in the same breath we’re gutting our nuclear nonproliferation by 15 or 20 percent. That would send a confusing message to the rest of the world.”

In response to a request for comment on the increased stockpile budget, the White House referred Mother Jones to the National Nuclear Security Administration, which responded, “The President remains committed to a safe, secure, and reliable nuclear deterrent.” John Noonan, a spokesman for the House Armed Services Committee, approved of the president’s nuclear spending choices. “Tight budgets require everyone to set priorities,” he wrote in an email. “In this case, sustaining the nuclear weapons stockpile is the NNSA’s central mission and an appropriate priority.”

It is not clear exactly how the president intended to accomplish the goals he articulated four years ago. The administration’s 2010 Nuclear Posture Review laid out several different options for reducing the United States’ nuclear stockpile, but it didn’t include hard numbers. And the specifics of the administration’s international nonproliferation efforts are classified. What is clear is that not all vulnerable nuclear material is in safe hands. Reif says there are still dozens of research reactors that remain to be converted from using weapons-grade highly enriched uranium, and that hundreds of pounds of highly enriched uranium remain unsecured.

A spokesperson for the White House Office of Management and Budget said in an email that the cuts to nonproliferation programs are the result of the NNSA, which oversees the nation’s nuclear stockpile and nonproliferation efforts, having completed Obama’s “2009-initiated effort to secure vulnerable nuclear materials.” But the OMB also says work remains to be done on disposing of weapons-grade nuclear materials, and that the NNSA will continue that work.

Robert Middaugh, a spokesman for the NNSA, reiterated this in an email. He wrote that the proposed budget cuts “were minor.” Middaugh pointed out that “we’re dismantling and eliminating nuclear weapons at a rate faster than even we had planned.”

Coyle says it’s nice that NNSA has made progress, “but if you took them literally” when the agency says that it has met all its goals, “then their budget next year should be zero.”