Illustration: Dale Stephanos

“That social norm is just something that has evolved over time” is how Mark Zuckerberg justified hijacking your privacy in 2010, after Facebook imperiously reset everyone’s default settings to “public.” “People have really gotten comfortable sharing more information and different kinds.” Riiight. Little did we know that by that time, Facebook (along with Google, Microsoft, etc.) was already collaborating with the National Security Agency’s PRISM program that swept up personal data on vast numbers of internet users.

In light of what we know now, Zuckerberg’s high-hat act has a bit of a creepy feel, like that guy who told you he was a documentary photographer, but turned out to be a Peeping Tom. But perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised: At the core of Facebook’s business model is the notion that our personal information is not, well, ours. And much like the NSA, no matter how often it’s told to stop using data in ways we didn’t authorize, it just won’t quit. Not long after Zuckerberg’s “evolving norm” dodge, Facebook had to promise the feds it would stop doing things like putting your picture in ads targeted at your “friends”; that promise lasted only until this past summer, when it suddenly “clarified” its right to do with your (and your kids’) photos whatever it sees fit. And just this week, Facebook analytics chief Ken Rudin told the Wall Street Journal that the company is experimenting with new ways to suck up your data, such as “how long a user’s cursor hovers over a certain part of its website, or whether a user’s newsfeed is visible at a given moment on the screen of his or her mobile phone.”

There will be a lot of talk in coming months about the government surveillance golem assembled in the shadows of the internet. Good. But what about the pervasive claim the private sector has staked to our digital lives, from where we (and our phones) spend the night to how often we text our spouse or swipe our Visa at the liquor store? It’s not a stretch to say that there’s a corporate spy operation equal to the NSA—indeed, sometimes it’s hard to tell the difference.

Yes, Silicon Valley libertarians, we know there is a difference: When we hand over information to Facebook, Google, Amazon, and PayPal, we click “I Agree.” We don’t clear our cookies. We recycle the opt-out notice. And let’s face it, that’s exactly what internet companies are trying to get us to do: hand over data without thinking of the transaction as a commercial one. It’s all so casual, cheery, intimate—like, like?

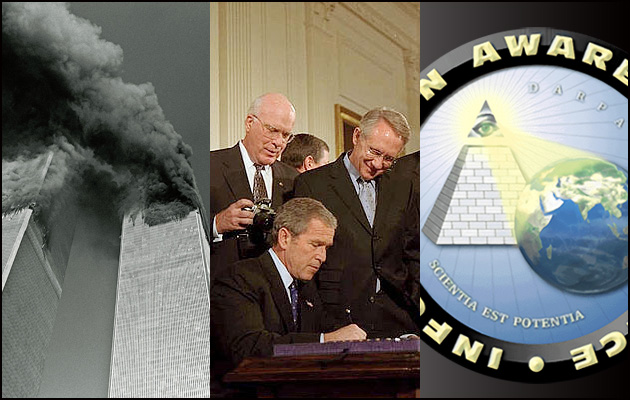

But beyond all the Friends and Hangouts and Favorites, there’s cold, hard cash, and, as they say on Sand Hill Road, when the product is free, you are the product. It’s your data that makes Facebook worth $100 billion and Google $300 billion. It’s your data that info-mining companies like Acxiom and Datalogix package, repackage, sift, and sell. And it’s your data that, as we’ve now learned, tech giants also pass along to the government. Let’s review: Companies have given the NSA access to the records of every phone call made in the United States. Companies have inserted NSA-designed “back doors” in security software, giving the government (and, potentially, hackers—or other governments) access to everything from bank records to medical data. And oh, yeah, companies also flat-out sell your data to the NSA and other agencies.

To be sure, no one should expect a bunch of engineers and their lawyers to turn into privacy warriors. What we could have done without was the industry’s pearl-clutching when the eavesdropping was finally revealed: the insistence (with eerily similar wording) that “we have never heard of PRISM”; the Captain Renault-like shock—shock!—to discover that data mining was going on here. Only after it became undeniably clear that they had known and had cooperated did they duly hurl indignation at the NSA and the FISA court that approved the data demands. Heartfelt? Maybe. But it also served a branding purpose: Wait! Don’t unfriend us! Kittens!

O hai, check out Mark Zuckerberg at this year’s TechCrunch conference: The NSA really “blew it,” he said, by insisting that its spying was mostly directed at foreigners. “Like, oh, wonderful, that’s really going to inspire confidence in American internet companies. I thought that was really bad.” Shorter: What matters is how quickly Facebook can achieve total world domination.

Maybe the biggest upside to l’affaire Snowden is that Americans are starting to wise up. “Advertisers” rank barely behind “hackers or criminals” on the list of entities that internet users say they don’t want to be tracked by (followed by “people from your past”). A solid majority say it’s very important to control access to their email, downloads, and location data. Perhaps that’s why, outside the more sycophantic crevices of the tech press, the new iPhone’s biometric capability was not greeted with the unadulterated exultation of the pre-PRISM era.

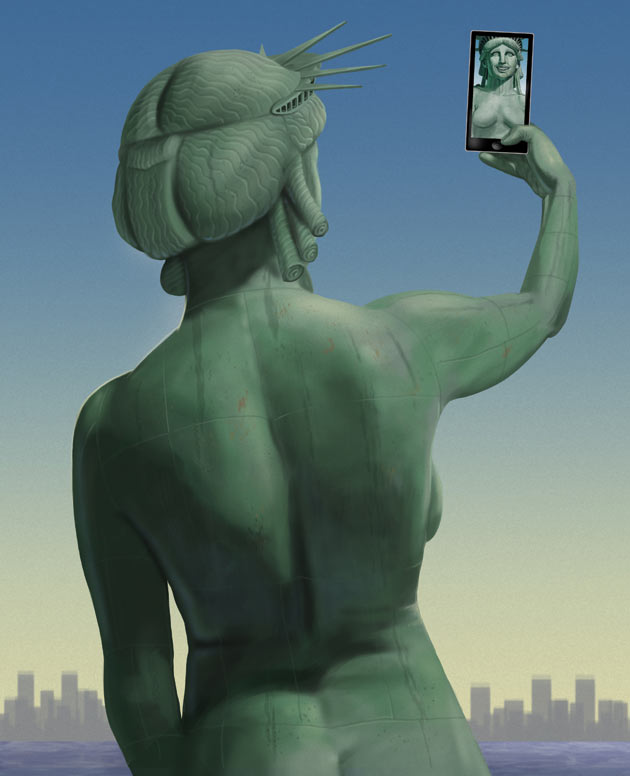

The truth is, for too long we’ve been content to play with our gadgets and let the geekpreneurs figure out the rest. But that’s not their job; change-the-world blather notwithstanding, their job is to make money. That leaves the hard stuff—like how much privacy we’ll trade for either convenience or security—in someone else’s hands: ours. It’s our responsibility to take charge of our online behavior (posting Carlos Dangerrific selfies? So long as you want your boss, and your high school nemesis, to see ’em), and, more urgently, it’s our job to prod our elected representatives to take on the intelligence agencies and their private-sector pals.

The NSA was able to do what it did because, post-9/11, “with us or against us” absolutism cowed any critics of its expanding dragnet. Facebook does what it does because, unlike Europe—where both privacy and the ability to know what companies have on you are codified as fundamental rights—we haven’t been conditioned to see Orwellian overreach in every algorithm. That is now changing, and both the NSA and Mark Zuckerberg will have to accept it. The social norm is evolving.