Grand Theft Auto V/Rockstar Games

It was one of the most brutal video games imaginable—players used cars to murder people in broad daylight. Parents were outraged, and behavioral experts warned of real-world carnage. “In this game a player takes the first step to creating violence,” a psychologist from the National Safety Council told the New York Times. “And I shudder to think what will come next if this is encouraged. It’ll be pretty gory.”

To earn points, Death Race encouraged players to mow down pedestrians. Given that it was 1976, those pedestrians were little pixel-gremlins in a 2-D black-and-white universe that bore almost no recognizable likeness to real people.

Indeed, the debate about whether violent video games lead to violent acts by those who play them goes way back. The public reaction to Death Race can be seen as an early predecessor to the controversial Grand Theft Auto three decades later and the many other graphically violent and hyper-real games of today, including the slew of new titles debuting at the E3 gaming summit this week in Los Angeles.

In the wake of the Newtown massacre and numerous other recent mass shootings, familiar condemnations of and questions about these games have reemerged. Here are some answers.

Who’s claiming video games cause violence in the real world?

Though conservatives tend to raise it more frequently, this bogeyman plays across the political spectrum, with regular calls for more research, more regulations, and more censorship. The tragedy in Newtown set off a fresh wave:

Donald Trump tweeted: “Video game violence & glorification must be stopped—it’s creating monsters!” Ralph Nader likened violent video games to “electronic child molesters.” (His outlandish rhetoric was meant to suggest that parents need to be involved in the media their kids consume.) MSNBC’s Joe Scarborough asserted that the government has a right to regulate video games, despite a Supreme Court ruling to the contrary.

Unsurprisingly, the most over-the-top talk came from the National Rifle Association:

“Guns don’t kill people. Video games, the media, and Obama’s budget kill people,” NRA Executive Vice President Wayne LaPierre said at a press conference one week after the mass shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary. He continued without irony: “There exists in this country, sadly, a callous, corrupt and corrupting shadow industry that sells and stows violence against its own people through vicious, violent video games with names like Bulletstorm, Grand Theft Auto, Mortal Kombat, and Splatterhouse.”

Has the rhetoric led to any government action?

Yes. Amid a flurry of broader legislative activity on gun violence since Newtown there have been proposals specifically focused on video games. Among them:

State Rep. Diane Franklin, a Republican in Missouri, sponsored a state bill that would impose a 1 percent tax on violent games, the revenues of which would go toward “the treatment of mental-health conditions associated with exposure to violent video games.” (The bill has since been withdrawn.) Vice President Joe Biden has also promoted this idea.

Rep. Jim Matheson (D-Utah) proposed a federal bill that would give the Entertainment Software Rating Board’s ratings system the weight of the law, making it illegal to sell Mature-rated games to minors, something Gov. Chris Christie (R-N.J.) has also proposed for his home state.

A bill introduced in the Senate by Sen. Jay Rockefeller (D-W.Va.) proposed studying the impact of violent video games on children.

So who actually plays these games and how popular are they?

While many of the top selling games in history have been various Mario and Pokemon titles, games from the the first-person-shooter genre, which appeal in particular to teen boys and young men, are also huge sellers.

The new king of the hill is Activision’s Call of Duty: Black Ops II, which surpassed Wii Play as the No. 1 grossing game in 2012. Call of Duty is now one of the most successful franchises in video game history, topping charts year over year and boasting around 40 million active monthly users playing one of the franchise’s games over the internet. (Which doesn’t even include people playing the game offline.) There is already much anticipation for the release later this year of Call of Duty: Ghosts.

The Battlefield games from Electronic Arts also sell millions of units with each release. Irrational Games’ BioShock Infinite, released in March, has sold nearly 4 million units and is one of the most violent games to date. (Read MoJo‘s interview with Irrational’s cofounder and creative director, Ken Levine.)

What research has been done on the link between video games and violence, and what does it really tell us?

Studies on how violent video games affect behavior date to the mid 1980s, with conflicting results. Since then there have been at least two dozen studies conducted on the subject.

“Video Games, Television, and Aggression in Teenagers,” published by the University of Georgia in 1984, found that playing arcade games was linked to increases in physical aggression. But a study published a year later by the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, “Personality, Psychopathology, and Developmental Issues in Male Adolescent Video Game Use,” found that arcade games have a “calming effect” and that boys use them to blow off steam. Both studies relied on surveys and interviews asking boys and young men about their media consumption.

Studies grew more sophisticated over the years, but their findings continued to point in different directions. A 2011 study found that people who had played competitive games, regardless of whether they were violent or not, exhibited increased aggression. In 2012, a different study found that cooperative playing in the graphically violent Halo II made the test subjects more cooperative even outside of video game playing.

Metastudies—comparing the results and the methodologies of prior research on the subject—have also been problematic. One published in 2010 by the American Psychological Association, analyzing data from multiple studies and more than 130,000 subjects, concluded that “violent video games increase aggressive thoughts, angry feelings, and aggressive behaviors and decrease empathic feelings and pro-social behaviors.” But results from another metastudy showed that most studies of violent video games over the years suffered from publication biases that tilted the results toward foregone correlative conclusions.

Why is it so hard to get good research on this subject?

“I think that the discussion of media forms—particularly games—as some kind of serious social problem is often an attempt to kind of corral and solve what is a much broader social issue,” says Carly Kocurek, a professor of Digital Humanities at the Illinois Institute of Technology. “Games aren’t developed in a vacuum, and they reflect the cultural milieu that produces them. So of course we have violent games.”

There is also the fundamental problem of measuring violent outcomes ethically and effectively.

“I think anybody who tells you that there’s any kind of consistency to the aggression research is lying to you,” Christopher J. Ferguson, associate professor of psychology and criminal justice at Texas A&M International University, told Kotaku. “There’s no consistency in the aggression literature, and my impression is that at this point it is not strong enough to draw any kind of causal, or even really correlational links between video game violence and aggression, no matter how weakly we may define aggression.”

Moreover, determining why somebody carries out a violent act like a school shooting can be very complex; underlying mental-health issues are almost always present. More than half of mass shooters over the last 30 years had mental-health problems.

But America’s consumption of violent video games must help explain our inordinate rate of gun violence, right?

Actually, no. A look at global video game spending per capita in relation to gun death statistics reveals that gun deaths in the United States far outpace those in other countries—including countries with higher per capita video game spending.

A 10-country comparison from the Washington Post shows the United States as the clear outlier in this regard. Countries with the highest per capita spending on video games, such as the Netherlands and South Korea, are among the safest countries in the world when it comes to guns. In other words, America plays about the same number of violent video games per capita as the rest of the industrialized world, despite that we far outpace every other nation in terms of gun deaths.

Or, consider it this way: With violent video game sales almost always at the top of the charts, why do so few gamers turn into homicidal shooters? In fact, the number of violent youth offenders in the United States fell by more than half between 1994 and 2010—while video game sales more than doubled since 1996. A working paper from economists on violence and video game sales published in 2011 found that higher rates of violent video game sales in fact correlated with a decrease in crimes, especially violent crimes.

I’m still not convinced. A bunch of mass shooters were gamers, right?

Some mass shooters over the last couple of decades have had a history with violent video games. The Newtown shooter, Adam Lanza, was reportedly “obsessed” with video games. Norway shooter Anders Behring Breivik was said to have played World of Warcraft for 16 hours a day until he gave up the game in favor of Call of Duty: Modern Warfare, which he claimed he used to train with a rifle. Aurora theater shooter James Holmes was reportedly a fan of violent video games and movies such as The Dark Knight. (Holmes reportedly went so far as to mimic the Joker by dying his hair prior to carrying out his attack.)

Jerald Block, a researcher and psychiatrist in Portland, Oregon, stirred controversy when he concluded that Columbine shooters Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold carried out their rampage after their parents took away their video games. According to the Denver Post, Block said that the two had relied on the virtual world of computer games to express their rage, and that cutting them off in 1998 had sent them into crisis.

But that’s clearly an oversimplification. The age and gender of many mass shooters, including Columbine’s, places them right in the target demographic for first-person-shooter (and most other) video games. And people between ages 18 and 25 also tend to report the highest rates of mental-health issues. Harris and Klebold’s complex mental-health problems have been well documented.

To hold up a few sensational examples as causal evidence between violent games and violent acts ignores the millions of other young men and women who play violent video games and never go on a shooting spree in real life. Furthermore, it’s very difficult to determine empirically whether violent kids are simply drawn to violent forms of entertainment, or if the entertainment somehow makes them violent. Without solid scientific data to go on, it’s easier to draw conclusions that confirm our own biases.

How is the industry reacting to the latest outcry over violent games?

Moral panic over the effects of violent video games on young people has had an impact on the industry over the years, says Kocurek, noting that “public and government pressure has driven the industry’s efforts to self regulate.”

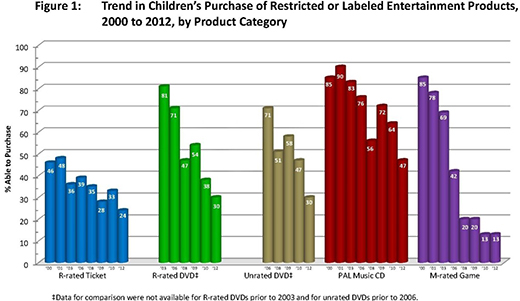

In fact, it is among the best when it comes to abiding by its own voluntary ratings system, with self-regulated retail sales of Mature-rated games to minors lower than in any other entertainment field, as this chart shows:

But is that enough? Even conservative judges think there should be stronger laws regulating these games, right?

There have been two major Supreme Court cases involving video games and attempts by the state to regulate access to video games. Aladdin’s Castle, Inc. v. City of Mesquite in 1983 and Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Association in 2011.

“Both cases addressed attempts to regulate youth access to games, and in both cases, the court held that youth access can’t be curtailed,” Kocurek says.

In Brown v. EMA, the Supreme Court found that the research simply wasn’t compelling enough to spark government action, and that video games, like books and film, were protected by the First Amendment.

“Parents who care about the matter can readily evaluate the games their children bring home,” Justice Antonin Scalia wrote when the Supreme Court deemed California’s video game censorship bill unconstitutional in Brown v. EMA. “Filling the remaining modest gap in concerned-parents’ control can hardly be a compelling state interest.”

So how can we explain the violent acts of some kids who play these games?

For her part, Kocurek wonders if the focus on video games is mostly a distraction from more important issues. “When we talk about violent games,” she says, “we are too often talking about something else and looking for a scapegoat.”

In other words, violent video games are an easy thing to blame for a more complex problem. Public policy debates, she says, need to focus on serious research into the myriad factors that may contribute to gun violence. This may include video games—but a serious debate needs to look at the dearth of mental-health care in America, our abundance of easily accessible weapons, our highly flawed background-check system, and other factors.

There is at least one practical approach to violent video games, however, that most people would agree on: Parents should think deliberately about purchasing these games for their kids. Better still, they should be involved in the games their kids play as much as possible so that they can know firsthand whether the actions and images they’re allowing their children to consume are appropriate or not.

Don’t miss MoJo‘s award–winning coverage of gun violence in America.