Former IRS Commissioner Doug Shulman. Christy Bowe/Globe Photos/ZUMApress.com

Former IRS Commissioner Douglas Shulman, a George W. Bush appointee who ran the tax agency when low-level employees wrongly singled out conservative groups for special scrutiny, testified on Tuesday before Congress for the first time since the scandal erupted on May 10. Senators hoping for new revelations or a mea culpa from Shulman, however, were left wanting. He said little about why IRS staffers targeted tea party groups and others for some 18 months, and he repeatedly downplayed his own role.

But one thing was clear from the hearing: The fallout from the IRS’ tea party debacle isn’t over, and its implications may spill over into campaign finance rules. J. Russell George, the Treasury Department inspector general who investigated the IRS’ actions, said his office will be auditing how the IRS oversees politically active nonprofit groups and presumably how the agency determines which nonprofits are too political. That’s potentially big news for the money-in-politics world: Nonprofits spent hundreds of millions of dollars during the 2012 campaign, and as the IRS scandal has further revealed, the agency’s process for determining how much politicking by a group runs afoul of regulations is vague and confusing.

Nor is George’s office finished with the IRS’ tea party mess. “Suffice it to say, this matter is not over as far as we are concerned,” he told members of the Senate finance committee.

During Tuesday’s hearing, the frustration and anger in the voices of senators was palpable, as Shulman and Steven Miller, the outgoing acting commissioner of the IRS, provided few answers. Shulman avoided taking any blame for the screw-ups of the Cincinnati-based IRS employees at the center of the scandal; he said he regretted that those actions took place on his watch, but referred senators back to the details described in the IG’s report. He dodged when Sen. John Cornyn (R-Texas) pressed him for more.

“The buck doesn’t stop with you?” Cornyn asked.

“I certainly am not personally responsible” for singling out any groups for extra scrutiny, Shulman replied.

Miller, for his part, apologized for what he has called the agency’s “obnoxious” behavior and its employees’ mistakes. IRS staffers lacked the training and expertise, he said, to deal with the influx of nonprofit applications and to vet those groups involved in politics. But Miller reiterated that the IRS’ mistakes were not the result of political bias.

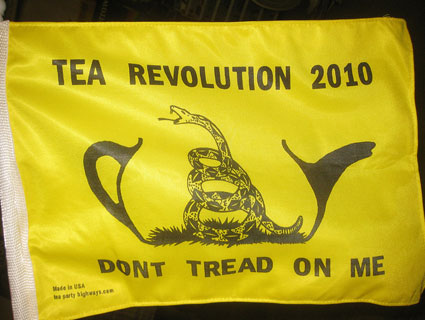

Many senators didn’t buy this. “On the face of it, it certainly appears that it’s completely politically motivated,” said Sen. Pat Toomey (R-Pa.). He noted that nobody in a position of responsibility seemed able to account for the decision to single out groups with “tea party” or “patriots” in the their name, or those with a focus on government debt or spending—criteria that the IG’s report called “inappropriate.” “What we need to do is to bring before this committee some people…who actually decided this was a good idea, who decided we ought to resume this after the initial malfeasance was ended,” Toomey said. “It’s frustrating to have no answers for a hearing like this.”

Sprinkled throughout the hearing were numerous exchanges over what politically active nonprofits can and can’t do—underscoring the tangle of laws and “guidance” intended to regulate nonprofits. Shulman, the former commissioner, said Congress should step in and straighten out the laws for nonprofits; Miller said there was more the IRS could do as well. Sen. Max Baucus (D-Mont.), the chair of the finance committee, wasn’t mollified. “Clearly, a Mack truck is being driven though the 501(c)(4) loophole,” he said, referring to politically active nonprofits of the kind that operated in the 2012 elections such as Karl Rove’s Crossroads GPS and the pro-Obama outfit Priorities USA.

On Wednesday, the House oversight committee is set to grill Shulman and Lois Lerner, an IRS director at the center of the debacle. Members of House will be just as frustrated as their Senate colleagues: Lerner plans to plead the fifth.