<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com">Stephen VanHorn </a>/Shutterstock

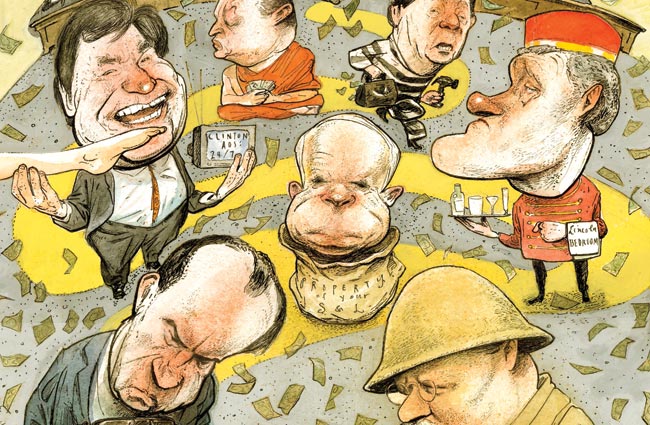

Big dark-money groups like the Karl Rove-advised Crossroads GPS promised the IRS they would have “limited” involvement in politics—in order to protect their nonprofit tax-exempt status—yet went on to spend hundreds of millions of dollars to influence the 2010 and 2012 federal elections. Now several tax policy experts, including a former high-ranking IRS official who ran the division overseeing nonprofits, say the IRS must bring the hammer down on these shadowy nonprofits or risk looking weak and useless.

“The government’s going to have to investigate them and prosecute them,” says Marcus Owens, who ran the IRS’s tax-exempt division for a decade and is now a lawyer in private practice. “In order to maintain the integrity of the process, they’re going to be forced to take action.”

In their initial applications seeking tax-exempt status under a particular provision of the tax code, section 501(c)(4), dozens of political nonprofits told the IRS their political spending would be limited or, in some cases, nonexistent. (Otherwise, they wouldn’t qualify for this advantageous tax status, which allows them to take foreign donations and hide the identities of their funders.) But ProPublica reported that many of those groups have spent big on politics. In 2008, for instance, the Iowa-based American Future Fund assured the IRS on its tax-exempt application that it would spend “no” money to influence elections; the same day the group mailed its application, it released a web ad hailing then-Sen. Norm Coleman (R-Minn.) and went on to spend $8 million on politicking in the 2010 elections. Americans for Responsible Leadership, an Arizona-based nonprofit, was more bold: It told the taxman it would engage in zero political work. It then spent $5.2 million backing Mitt Romney.

The most high-profile nonprofit to tell the IRS one thing and seemingly do another is Crossroads GPS, the powerful group cofounded by Karl Rove. In a 41-page application, dated September 3, 2010, Crossroads told the IRS it would spend only a “limited” amount of money on influencing elections. Crossroads is different from the two groups mentioned above in a crucial way: The IRS has yet to approve its tax-exempt application, which means its 2010 application is confidential. Yet ProPublica obtained it and exposed the gap between what Crossroads said in September 2010 and what it went on to do.

Despite telling the IRS it would spend a “limited” amount of money on politics, Crossroads unloaded nearly $16 million in dark money on political advertising during the 2010 campaign and more than $70 million to influence the presidential and congressional contests in 2012.

Tax experts, including Owens, the former IRS director, say the IRS appears to have been duped by these groups. (Super-PACs, the other big spending vehicles in recent elections, must disclose all donors and spending and are not regulated by the IRS.) “If [IRS officials] allow a large number of these organizations to knowingly say anything they want on their applications and almost immediately turn around do the opposite,” Owens says, “that really erodes the integrity of the process.” (The IRS did not respond to a request for comment.)

Nonprofit groups like American Future Fund and Americans for Responsible Leadership* and their lawyers sign their tax-exempt applications under penalty of perjury, Owens notes. If the IRS did decide to bring actions against certain nonprofit groups, it would need to prove that those groups knowingly tried to mislead agency about their plans. For instance, did a nonprofit tell its donors it planned to spend heavily on elections, but tell the IRS something different? Having worked on the inside of the IRS, Owens says it’s a tough very case to build. (That might explain why the IRS audit rate for 501(c)(4) groups clocks in at less than 1 percent.) That said, the IRS isn’t the only agency that can prosecute law-breaking nonprofits; the Department of Justice can also take action. But it rarely does, Owens says.

Crossroads GPS spokesman Jonathan Collegio declined to comment. An American Future Fund spokeswoman did not respond to requests for comment. Neither did Jason Torchinsky, a lawyer for Americans for Responsible Leadership. But Torchinsky recently wrote an email to the editor at the Arizona Capitol Times saying that ARL had amended its tax-exempt application and “corrected the error that was the central feature” of the ProPublica story—namely, that ARL’s initial application said it would spend no money on politics.

Frances Hill, a University of Miami law professor and an expert on nonprofits, says she agrees with Owens that the government must crack down on groups that seemingly misled the government about their true intentions. Ditto Donald Tobin, a law professor at Ohio State University. “There really is serious concern about our current process, both the actual rules surrounding [these groups] but also the misuse and in some case unethical conduct” of those using 501(c)(4) nonprofits, he says. “It’s really disturbing on a whole set of fronts.”

Tax experts like Owens, Hill, and Tobin aren’t the only ones prodding the IRS to take action. Campaign finance watchdogs have hounded the agency for years for not investigating and punishing politically active nonprofits. In a letter dated January 2, lawyers with the Campaign Legal Center and Democracy 21, two groups that favor more regulation of political money, urged the IRS to officially deny tax-exempt status to Rove’s Crossroads GPS. (The group’s application is technically still pending.) “Crossroads GPS served as little more than a campaign operation in 2012,” the lawyers wrote.

Collegio, the Crossroads spokesman, has dismissed the letter as “the 25th identical letter that the partisans and ideologues at the Campaign Legal Center have sent to the IRS, and it doesn’t merit anyone’s attention.”

Hill says she doubts whether the IRS has the “political will” to go after political nonprofit groups, which spent well over $400 million on the 2012 elections and often have direct ties to top Democratic and Republican lawmakers. Yet what’s at stake, Hill adds, is nothing less than the very integrity of the tax law. “We have tax laws on the books—the question now is, does the IRS intend to enforce the law?” she asks. “Or are we all just going to pretend that the laws are going to be enforced?”

*This sentence has been corrected. Click here to return to the story.