<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/gallery-302563p1.html?cr=00&pl=edit-00">Ryan Rodrick Beiler</a>/Shutterstock.com

When President Barack Obama decided to allow undocumented immigrants who were brought to the United States as children to stay in the country and work, Republicans blew a gasket. Sen. Jon Kyl (R-Ariz.) raised the possibility of impeachment. Rep. Steve King (R-Iowa) vowed to sue the administration in court to block the move. And Rep. Lamar Smith (R-Texas), the chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, accused Obama of putting “partisan politics and illegal immigrants ahead of the rule of law and the American people.” The GOP line: Obama went rogue and exceeded his constitutional powers.

Yet Kadiatou Diallo and thousands of other undocumented immigrants like her are living proof that Kyl, King, and Smith are unjustifiably hyperventilating about Obama overstepping his authority.

Diallo is in America because of George W. Bush. She came to the United States from Guinea in 1999, after her son died in a hail of 41 bullets, shot by New York City police officers who said they believed the wallet in his hand was a gun. Diallo—and her family—overstayed their visas. But rather than deport her, immigration authorities granted her deferred action (lawyer-speak for temporarily delayed deportation) and work authorization—and continued to do so every two years, for the entire time Bush was in office.

“This is what my family uses to go to work, pay taxes,” Diallo says. “It’s the only thing we depend on now.”

Diallo is a prime example of how presidents from both parties have long claimed the authority to grant temporary stays of deportation and work authorization to undocumented immigrants. In a series of memos issued after the 1996 Illegal Immigration Reform and Responsibility Act, a law that sought to curtail illegal immigration and prioritize removal of unauthorized immigrants, immigration officials in both the Clinton and Bush administrations established guidelines and limits for when authorities could exercise leniency in dealing with unauthorized immigrants.

“The [immigration] guidelines we issued in 2000 were not rescinded,” says Doris Meissner, a top immigration official in the Clinton administration who is now a senior fellow at the Migration Policy Institute (MPI), a nonpartisan think tank that studies migration. “They’re in place today; they were observed by the Bush administration.” Those guidelines were driven in part by complaints that, as a bipartisan group of members of Congress argued in a 1999 letter to the Clinton Justice Department, the deportation process was “unfair” and resulted in “unjustifiable hardships.” Smith signed that letter, which urged “discretion in removal proceedings.” But now the congressman says the president is undermining the rule of law.

Bush officials didn’t just embrace the idea that the government can prioritize whom to deport—they expanded it. “The universe of opportunities to exercise prosecutorial discretion is large,” Bush immigration adviser William Howard wrote in a 2005 memo. Howard recommended letting people stay in the country when “compelling reasons exist,” such as an unauthorized immigrant being a relative of a US servicemember or for “sympathetic humanitarian factors.”

Julie L. Myers, another Bush-era immigration official, issued another follow-up memo in 2007, advising immigration officials to consider letting people who had health problems or were taking care of sick relatives remain in the United States.

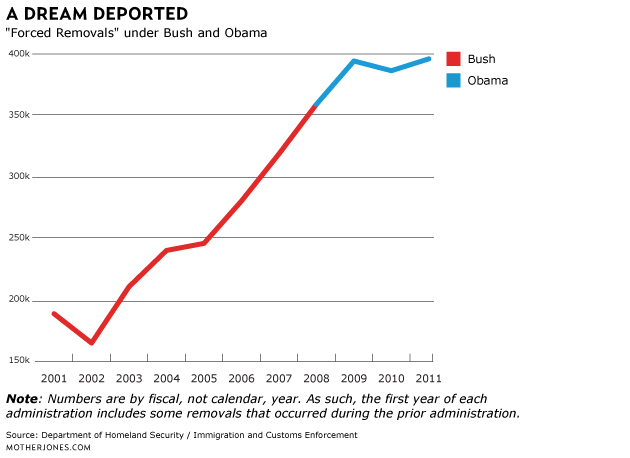

The powers Obama exercised in June decision weren’t new. They don’t grant any of the unauthorized immigrants legal status or citizenship, and it would be a simple matter for a future president to change the rules again and deport the people Obama allowed to stay. And up until now, the Obama administration has been aggressive in pursuing deportations of unauthorized immigrants, removing more than a million since taking office. This chart shows how deportations have risen since Bush took office:

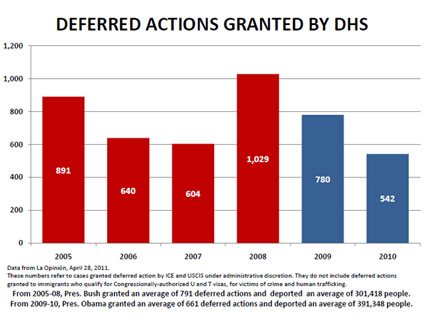

Republicans are right about one thing in this controversy: The Obama administration is using the government’s immigration powers on a greater scale than they were previously used. A June analysis from the MPI estimates that 1.4 million unauthorized immigrants could benefit from the administration’s new policy. That’s a big change. As the chart below shows, until now Obama had actually granted fewer deferred actions than his predecessor—a little over 500 in 2010 compared to more than 1,000 in the last year of the Bush administration:

Via America’s Voice

Via America’s Voice

If the MPI estimate is correct, the 2012 bar on a future version of this chart will be many times higher than the 2009 and 2010 bars. One of people who might be included in that 2012 number is Oleg Chashchukhin, a 22-year-old in Maryland whose father brought him here from Russia when he was seven. Chashchukhin has been getting by doing odd jobs like fixing cars. He has an associate degree in information services technology from a community college in Maryland, but he can’t afford to attend a four-year school in the state because of the out-of-state tuition rate. If he manages to acquire work authorization from DHS, he’ll be able to find regular work. Chashchukhin’s father was so excited that he actually taped Obama’s announcement of the new policy so his son could watch it.

“I couldn’t believe that [Obama] even actually did it,” Chashchukhin says. “He’s the first one that actually even tried to do anything for people who are in the same boat I am.”