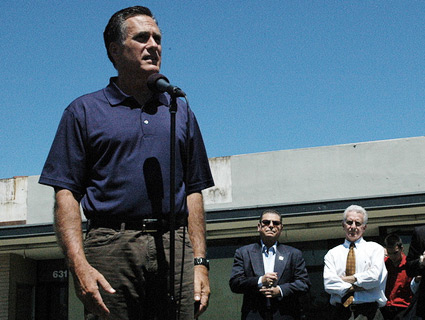

Illustration: Steve BrodnerInside a cramped doctor’s office near a busy thoroughfare in Alexandria, Virginia, two women are getting their faces buzzed with a faintly humming device that looks like an electric razor. It’s a “galvanic spa,” and its electrical charges, combined with special gels and serums, are supposed to target “youth gene clusters” and reverse the effects of aging. But the group of about 20 men and women gathered here haven’t come just for the free skin-care treatments. They’re here to learn about a business opportunity.

Illustration: Steve BrodnerInside a cramped doctor’s office near a busy thoroughfare in Alexandria, Virginia, two women are getting their faces buzzed with a faintly humming device that looks like an electric razor. It’s a “galvanic spa,” and its electrical charges, combined with special gels and serums, are supposed to target “youth gene clusters” and reverse the effects of aging. But the group of about 20 men and women gathered here haven’t come just for the free skin-care treatments. They’re here to learn about a business opportunity.

This is a recruiting session for the Utah-based multilevel-marketing (MLM) company Nu Skin, which sells vitamins, dietary supplements, and beauty products through a network of independent distributors. The meeting is led by an energetic 42-year-old named Martha Sanchez, who frames her pitch with a lengthy explanation of just how hard it is to save for retirement. She flashes slides that illustrate how much of a nest egg you need to generate $5,000 a month in “residual” income: At 5 percent interest, it’s a staggering $1.25 million.

The promise of a steady flow of passive income lies at the heart of Nu Skin’s pitch. Its business model entails recruiting distributors, who in turn recruit more distributors, and so on, with each layer kicking the proceeds up the chain. Theoretically, as your “downline” grows, so do your monthly commission checks, even as your own effort diminishes.

Unlike franchises, which Sanchez notes can be stressful to run and require a big up-front investment, Nu Skin offers a low barrier to entry. Anyone who ponies up $1,198 can secure a “business builder” package that includes two galvanic spas and all the goo that goes with them to deploy on potential clients.

Sanchez walks the group through Nu Skin’s various levels. Those who reach “executive” status, which is most easily accomplished by recruiting four more distributors, can earn an average of $10,000 a year. It’s not much, she notes, but it’s often enough to keep a family out of bankruptcy. Bring in eight executives and that’s a new ballgame: “That’s when you start making over $10,000 a month.”

Nu Skin has created more than 800 millionaires, Sanchez insists. She has even brought one along: Art Farrington, a “blue diamond” distributor who she says earns more than $500,000 a year.

Farrington is also on hand to give a personal demonstration of Nu Skin’s products. A former fighter pilot, he’s in his 70s and says he’s been using the galvanic spa on one side of his neck and face, leaving the other side untouched. He models the untreated side, then the treated one, tilting his head slightly so that the wrinkles smooth out a bit. I can’t see any difference, but the other Nu Skin distributors respond with oohs, and the newcomers nod in approval.

Mike Sinisgalli is ready to get in on the action. He’s an ex-Army officer and says he’s decided to throw in with Nu Skin because he’s “trying to lead a healthy lifestyle” and wants to pursue “something that bears the fruit of my own efforts.” He was persuaded by an advertising supplement to the Wall Street Journal that ranked Nu Skin as one of the top “direct selling” companies in the country. “This, I can build it and I can keep it,” he says.

Like other MLM firms that advertise financial independence in uncertain times, Nu Skin’s stock price has skyrocketed, increasing from $9 in March 2009 to $54 this past March. Last year it posted a record $1.7 billion in revenue. And Nu Skin has accomplished this despite a controversial history of regulatory actions and lawsuits that have alleged it is little more than a pyramid scheme—a company whose primary customer base is its growing galaxy of distributors.

With Nu Skin’s growth has come significant political influence, particularly in Utah. As governor, Jon Huntsman brought company executives on a trade mission to China, where Nu Skin has been eager to gain a foothold.

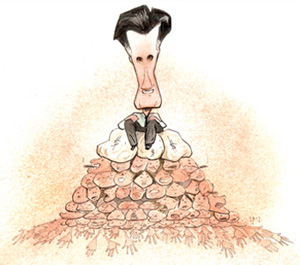

Nu Skin also has key supporters in Congress, including Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah), the ranking member of the Senate Finance Committee. Where Nu Skin was once the target of federal investigations, last year Hatch invited its top lawyer to testify before Congress on trade policy. The company’s former spokesman, Jason Chaffetz, is now a Utah congressman. “These are good companies to have in Utah,” he told the Salt Lake Tribune in October. And then there’s Mitt Romney, whose ties to Nu Skin and other MLM companies have yielded a torrent of campaign cash to fuel his presidential bid.

In 1999, Nu Skin’s 10th international convention featured a speech by the CEO of the organizing committee for Salt Lake City’s 2002 Winter Olympics, who had managed to secure a $20 million sponsorship from the company. The deal had helped to close some of the revenue shortfall plaguing the games, so Romney was effusive in his gratitude. Nu Skin and the Olympics had something in common, he told the 10,000 distributors in attendance: Both are “about taking control of your life and managing your own destiny.”

Speaking at the same event, Nu Skin’s then-president, Steven Lund, didn’t dispel the impression that the company was trying to buy its way to legitimacy. “We have aligned ourselves with the Olympics because this alignment helps you do your jobs better,” he said, according to the Deseret News, promising that the Olympic logo newly affixed to distributors’ business cards would bring in loads of new recruits.

Years later, as Romney embarked on his first presidential bid, Nu Skin—founded and led by Mormons—was a natural base of support. The company’s founder and chairman, Blake Roney, became a bundler for Romney’s 2008 campaign. Roney was also a partner at Rainmaker Sports and Entertainment, a Utah consulting firm that worked for the Romney campaign in 2008. Nu Skin employees donated more than $50,000 to Romney during that election cycle.

Three years later, as Romney was ramping up his current presidential bid, a handful of his former aides launched a super-PAC, Restore Our Future. When it filed its first financial report, two donations stood out—$1 million each from a pair of companies called Eli Publishing and F8 LLC. The Provo, Utah, address both firms gave traced back to an accounting firm that doubled as the official address of a foundation created by Nu Skin cofounder Sandra Tillotson. Corporate records show that the registered agents of Eli Publishing and F8 were, respectively, Steven Lund and his son-in-law.

When a local television reporter caught up with Lund to ask about the contributions, he said he had donated through a shell company for accounting reasons. But campaign finance watchdogs, who filed complaints with the Federal Election Commission, alleged the intent was to mask the money’s source.

Nu Skin isn’t Romney’s only connection to the MLM industry. Gordon Morton, cofounder of the supplement company Xango (the self-described creator of the mangosteen beverage “category”), served on his 2008 campaign’s finance committee. This past January, David Lisonbee, founder of the Sandy, Utah-based MLM company 4Life Research, donated $500,000 to Restore Our Future. And Romney’s current finance chair, Frank VanderSloot, is the CEO of Idaho-based Melaleuca, a multilevel-marketing company that sells green cleaning products and nutritional supplements.

Melaleuca and its subsidiaries contributed $1 million to Restore Our Future last year. In 2010, Romney had lavishly praised the firm on the occasion of its 25th anniversary: “Under the leadership of Frank VanderSloot,” he said in a statement, “Melaleuca has delivered on its promise of enhancing the lives of people.”

Utahns have a joke about multilevel-marketing companies: MLM really stands for “Mormons Losing Money.” The notion of selling to one’s friends and neighbors is so intertwined with the culture that the final season of HBO’s Big Love featured an MLM subplot. According to the Salt Lake Tribune, Utah has the highest concentration of such companies in the country.

There’s a reason why MLMs, many of which peddle natural health products like Nu Skin’s dietary supplements, have thrived there. Mormon scripture encourages the use of herbs as God’s medicine, and the faith has a strong tradition of turning to alternative medicine. Its founder, Joseph Smith, reportedly shunned traditional doctors, believing a physician had killed his brother. The tight-knit Latter-day Saints community, and the trusting nature of its adherents, have made Utah a lucrative terrain for multilevel marketers. Mormons, who typically spend two years serving as missionaries, are also natural recruits for companies that need salespeople with a high tolerance for rejection. And finally, MLM firms often pitch themselves to women as a way to stay home with their kids while still earning substantial incomes.

Yet for all the empowerment rhetoric, companies like Melaleuca and Nu Skin appear to subsist in large part on the hopes and fears of Americans losing their grip on financial security. Industry watchdog Robert L. FitzPatrick says Nu Skin’s business model “sets the average person upon his neighbor to get at his assets, savings, and investments.” Their structure—vast numbers of foot soldiers feeding a tiny layer of top earners—may not offend Romney, who has dismissed questions about income inequality as a matter of “envy.” But a close association with companies that seem to prey on consumers might not play well for a candidate who has battled allegations that the private equity firm he cofounded, Bain Capital, engaged in vulture capitalism. (Romney’s campaign did not respond to requests for comment.)

On the campaign trail, Romney has repeatedly stressed his commitment to the middle class—to the point of remarking in one interview that he was “not concerned about the very poor” or “the very rich” but rather “the 90 to 95 percent of Americans who right now are struggling.” But the hardworking conservatives Romney is courting—and has struggled to connect with—are the very same demographic that MLM companies are recruiting in droves.

Throughout its early years, Nu Skin was dogged by consumer advocates, regulators, and lawyers representing aggrieved distributors who claimed the company was an illegal investment scheme. In one 1991 case, a former Nu Skin distributor in California filed a class action asserting that as many as 100,000 people had lost $75 million by signing up with the company. Nu Skin settled in 1992 and gave distributors $16 million in refunds for merchandise they were sitting on. A group of Canadian distributors brought a case against Nu Skin that was settled in 2001 with a similar outcome.

During the 1990s, Nu Skin entered into settlements with the attorneys general of Connecticut, Florida, Illinois, Michigan, Ohio, and Pennsylvania after a rash of complaints from distributors. Michigan’s attorney general threatened the company with a lawsuit, accusing it of operating a pyramid scheme and violating state consumer protection laws. Nu Skin settled the case without admitting wrongdoing and agreed to pay $25,000 to cover the state’s costs and give refunds to anyone who returned its products. In Connecticut, then-Attorney General Richard Blumenthal filed suit in 1992 alleging that Nu Skin was engaging in deceptive business practices. The company paid $85,000 to settle that case, in an agreement that had similar terms to those in Michigan. Two years later the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) cracked down on Nu Skin for making false claims about its products—including weight-loss supplements and baldness cures—and misrepresenting what new distributors would earn. (Its marketing materials blared: “If you’re not earning $10,000 a month or more We Need To Talk!” and “$14,000 a month…$168,000 a year…A lot of other people are doing it right now.”)

In 1994 Nu Skin signed a consent order with the FTC promising not to engage in false advertising and to cease misleading potential distributors. Three years later, it paid $1.5 million in civil penalties for violating the order.

That order, which bars the company and its distributors from making claims about potential financial returns without prominently disclosing the average earnings of distributors, is still in force. But at the meeting in Alexandria, and another I attended, there was near-nonstop talk of the fantastic opportunities available through Nu Skin, and very little in the way of qualifiers. At neither of these meetings did I receive information about what a typical distributor actually makes. (Nu Skin declined to respond to a detailed list of questions for this story.)

Though Sanchez touted blue-diamond distributor Farrington as proof of the potential for six-figure earnings with Nu Skin, the company’s disclosure forms tell a different story. In 2010 only 13 percent of its active US distributors received any kind of monthly commission, the documents show. The average was $119 a month—and that’s before factoring in the cost of the Nu Skin products and marketing materials distributors are told to purchase. (To become a distributor, you are urged to buy the business builder pack at $1,198; to remain in good standing at the next “executive” level, you must sell, on your own or through the people you’ve signed up, at least $2,000 worth of merchandise each month.)

The victims of multilevel marketing are largely invisible. Their losses are often too small to spur significant litigation. Many are convinced that if they fail to succeed as distributors, it’s because they didn’t try hard enough, not because the deck was stacked against them. Further cementing the code of silence, the victims of multilevel-marketing schemes are often perpetrators as well. “Because of the endless chain of recruitment, everyone who’s been recruited has brought their friends and family into the business,” explains Jon Taylor, who founded the Consumer Awareness Institute, an MLM watchdog group.

Taylor, a Utah native, has seen multilevel marketing from the inside, working for a year as a Nu Skin distributor in 1994. His disillusionment with the industry came after realizing that he was spending some $1,500 a month on Nu Skin training materials, products, publications, conferences, and advertising—all to get $246 in monthly commission checks. And he says he was one of the lucky ones. He hears regularly from people who feel they’ve been scammed by MLMs, but he’s rarely persuaded any to come forward and go public with their stories. “There’s a huge fear element,” he says.

These days federal regulators seem distinctly less interested in policing MLMs than they were in the 1990s. An FTC spokeswoman pointed to a 2007 suit the commission brought against now-defunct MLM firm BurnLounge, which focused on the music industry. But the FTC has brought only a handful of cases against such companies in the past decade, despite the industry’s explosive growth and a steady stream of letters to the commission about MLM business practices.

The era of diminished enforcement coincided with the presidency of George W. Bush, who seeded the FTC with MLM supporters after getting elected with substantial campaign cash from Amway, one of the nation’s oldest multilevel-marketing companies.

In 2001, Bush installed Tim Muris, a lawyer whose firm once represented Amway, as the commission’s chairman. David Scheffman, who was named director of the FTC’s bureau of economics, had previously served as an expert witness for Equinox, a multilevel-marketing firm that was shut down by the FTC during the Clinton administration. The revolving door spun the other way as well: Jodie Bernstein, the head of the FTC’s consumer protection division in the Clinton administration, became an Amway lobbyist, fighting proposed regulations that would have required MLM companies to disclose more information to potential distributors.

MLMs “desperately want to avoid being regulated,” says Douglas Brooks, the lawyer who represented the Canadian Nu Skin distributors in their class action. “Disclosure is death.”

That could be one reason why Nu Skin, like other MLMs, has increasingly set its sights overseas. Its record-breaking revenue, and its rising stock price, are largely the result of its entry into foreign markets, where it has found an untapped supply of potential distributors and, often, the added benefit of weaker regulation. Nearly 90 percent of the company’s revenue now comes from overseas, particularly from Asia.

In November, at a Nu Skin “opportunity meeting” held in the banquet room of a Marriott in Tysons Corner, Virginia, Cheryl Huffman gushed about how the company can help families find true prosperity. A former elementary-school teacher from West Virginia with a warm voice and a fondness for words like “heart,” she told the audience of about 150 that finding Nu Skin had allowed her to stay home with her kids while still earning a great living. She said she had just joined Nu Skin’s “million-dollar club.”

Huffman was a success story—the kind of person Romney refers to on the campaign trail when he lays out his vision of an “opportunity society” in which people who succeed through hard work “merit the rewards they are able to enjoy.” It’s a you-too-can-make-it maxim that aligns directly with Nu Skin’s pitch; perhaps it’s no wonder, then, that the company has invested so heavily in Romney’s campaign. With a history of troubled relations with government regulators, its executives must appreciate the value of having friends in high places.

Back in Tysons Corner, Huffman told the crowd she had a stock response when people ask about her business. “You know what I sell?” she said. “I sell hope to people. Our very best product is the hope we give to people.”