Nuclear trucking routes in the US Jeff Berlin

Nuclear trucking routes in the US Jeff Berlin

“Is that it?” My wife leans forward in the passenger seat of our sensible hatchback and points ahead to an 18-wheeler that’s hauling ass toward us on a low-country stretch of South Carolina’s Highway 125. We’ve been heading west from I-95 toward the Savannah River Site nuclear facility on the Georgia-South Carolina border, in search of nuke truckers. At first the mysterious big rig resembles a commercial gas tanker, but the cab is pristine-looking and there’s a simple blue-on-white license plate: US GOVERNMENT. It blows by too quickly to determine whether it’s part of the little-known US fleet tasked with transporting some of the most sensitive cargo in existence.

As you weave through interstate traffic, you’re unlikely to notice another plain-looking Peterbilt tractor-trailer rolling along in the right-hand lane. The government plates and array of antennas jutting from the cab’s roof would hardly register. You’d have no idea that inside the cab an armed federal agent operates a host of electronic countermeasures to keep outsiders from accessing his heavily armored cargo: a nuclear warhead with enough destructive power to level downtown San Francisco.

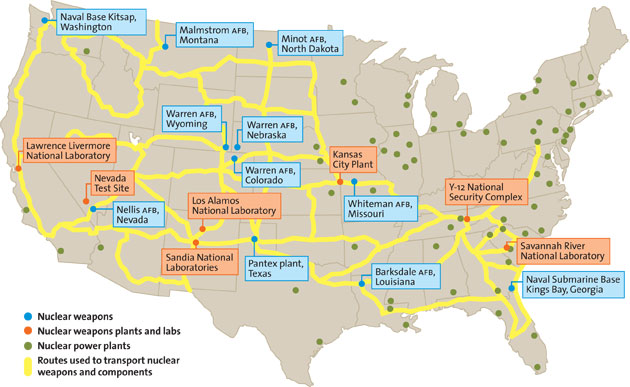

That’s the way the Office of Secure Transportation (OST) wants it. At a cost of $250 million a year, 350 couriers employed by this secretive agency within the US Department of Energy use some of the nation’s busiest roads to move America’s radioactive material wherever it needs to go—from a variety of labs, reactors and military bases, to the nation’s Pantex bomb-assembly plant in Amarillo, Texas, to the Savannah River facility.* Most of the shipments are bombs or weapon components; some are radioactive metals for research or fuel for Navy ships and submarines.

The OST’s operations are an open secret, and much about them can be gleaned from unclassified sources in the public domain. Yet hiding nukes in plain sight, and rolling them through major metropolises like Atlanta, Denver, and LA, raises a slew of security and environmental concerns, from theft to terrorist attack to radioactive spills. “Any time you put nuclear weapons and materials on the highway, you create security risks,” says Tom Clements, a nuclear security watchdog for the nonprofit environmental group Friends of the Earth. “The shipments are part of the threat to all of us by the nuclear complex.” To highlight those risks, his and another group, the Georgia-based Nuclear Watch South, have made a pastime of pursuing and photographing OST convoys.

Proponents say that the most efficient and reliable way to transport nuclear weapons and components is via the interstate highway system—a legacy of President Eisenhower, who pushed to build it as a national defense infrastructure during the Cold War in the 1950s. But Dr. Matthew Bunn, a Harvard professor who advised the Clinton White House on how to keep nuclear materials secure, acknowledges that nuclear convoys carry risks. “A transport is inherently harder to defend against a violent, guns-blazing enemy attack than a fixed site is,” he says. Moreover, in recent years the OST’s nuke truckers have had a spotty track record—including spills, problems with drinking on the job, weapons violations, and even criminal activity.

The OST doesn’t employ your typical truck-stop 18-wheeler jockeys; the agency seeks to hire military veterans, particularly ex-special-operations forces. Besides contending with “irregular hours, personal risks, and exposure to inclement weather,” agents “may be called upon to use deadly force if necessary to prevent the theft, sabotage or takeover of protected materials by unauthorized persons.” At a small outpost in Ft. Smith, Arkansas—the Army base where Elvis was inducted and got his famous haircut—the prospective agents are trained in close-quarters battle, tactical shooting, physical fitness, and shifting smoothly through the gears of a tractor-trailer.

In 2010, DOE inspectors were tipped off to alcohol abuse among the truckers. They identified 16 alcohol-related incidents between 2007 and 2009, including one in which agents were detained by local police at a bar after they’d stopped for the night with their atomic payload. After several agents and contractors were caught bringing unauthorized guns on training missions in Nevada between 2001 and 2004, DOE inspectors determined that “firearms policies and procedures were systematically violated.” One OST agent in Texas pled guilty in 2006 after using his position to illegally buy and sell body armor, rifle scopes, machine gun components, and other assault gear.

There have also been accidents. In 1996, a driver flipped his trailer on a two-lane Nebraska hill road after a freak ice storm, sending authorities scrambling to secure its payload of two nuclear bombs and return them to a nearby Air Force base. In 2003, two trucks operated by private contractors had rollover accidents in Montana and Tennessee while hauling uranium hexafluoride, a compound use to enrich reactor and bomb fuel. (DOE apparently uses some contractors for “low-risk” shipments, while all high-security hauling of weapons is done by OST truckers). In June 2004, on I-26 near Asheville, North Carolina, a truck bound for the Savannah River Site leaked “less than a pint” of uranyl nitrate—liquefied yellowcake uranium, which can be used to produce bomb components.

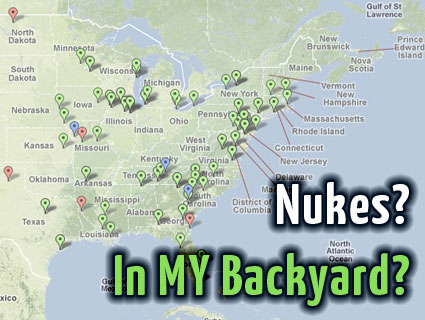

View Mother Jones: America’s Nuclear Facilities in a full-screen map. Source information

None of these incidents resulted in significant danger to locals, according to DOE records. Still, officials in Nevada, raising concerns in 2002 about possible federal shipments of nuclear waste to Yucca Mountain, cited the DOE’s own study stating that a “reasonably foreseeable accident scenario” could cause cancer-related deaths. And a bomb or rocket attack on a truck, DOE had projected, could kill 18,000 people and cost $10 billion to clean up. Such concerns led some activists to dub nuke truckers “the axles of evil.”

Al Stotts, a spokesman for the National Nuclear Security Administration, which oversees OST, declined to comment specifically on any measures taken to increase safety or security. “While we routinely acknowledge that OST’s mission is to transport national security cargoes—nuclear weapons, components and special nuclear materials—we don’t discuss routes, route timing, destinations or specific cargoes of convoys,” he said in an email. “I’m sure you also realize that for national security reasons we do not discuss vehicle tactical roles and capabilities, trailer system details, or operational force numbers and capabilities.”

If a terrorist attempted to attack or take over one of OST’s vehicles (not only 18-wheelers, but also fleet trucks, vans, and even dune buggies), they would have to contend with a lot more than just the specially trained agents manning them. “The trucks have all sorts of goodies, the details of which are mostly secret,” Bunn says. The cabs are fitted with custom composite armor and lightweight armored glass, as well as redundant communications systems that link the convoys to a monitoring center in Albuquerque. A driver has the ability to disable the truck so it can’t be moved or opened, and the truck is designed to defend itself, OST officials claim. How so remains unclear, though its parent agency, the DOE, contracted in 2005 with an Australian weapons company called Metal Storm to develop a robotic 40-millimeter gun that could “distribute large quantities of ammunition over a large area in an extremely short time frame.”

*Correction: The article originally stated that OST employs 600 couriers; it employs 350, among a total staff of 600.

Truck: Aleksandr Volodin/istock; Missile: simplesample/shutterstock

Truck: Aleksandr Volodin/istock; Missile: simplesample/shutterstock

The mystery surrounding nuke truckers has given rise to conspiracy theories. In May 2008, several locals near Needles, California, reported seeing a fiery blue-green UFO crash. Intrigued by the UFO story, Las Vegas investigative TV reporter George Knapp traveled to the alleged crash site—and stumbled upon a convoy of OST agents.

After some wangling, the agents offered Knapp a look at their trucks and operations. “They’re a little bit 007, with maybe a dash of Rambo, but maybe the smarts and technology of a Tom Clancy hero,” he told his viewers. The truckers denied any involvement with a UFO, but they confirmed that they spend a lot of time training in and hauling materials out of DOE’s Nevada Test Site—adjacent to the fabled Area 51.

As sophisticated as the vehicles apparently are, problems have also cropped up with planning and equipment. A 2007 DOE safety report found that the trucks’ emergency checklists in many cases recommended smaller-than-advisable quarantine areas around an accident site, potentially putting bystanders and first responders at risk. In 2002, the DOE approved a plan to haul plutonium parts from Rocky Flats, Colorado, to Savannah River and the Lawrence Livermore nuclear lab in California—using 45-gallon cans that had failed government crush tests. According to internal documents, several DOE engineers worried that if a truck carrying the radioactive cans were “hit by a train” or “hit from behind by a large, heavy vehicle, the crush environment may occur.” The plan was scrapped after California anti-nuclear activists obtained copies of the documents through a FOIA request.

Ellenton monument park Adam Weinstein

Ellenton monument park Adam Weinstein

The stretch of Highway 125 that runs through the middle of the 200,000-acre Savannah River Site is surrounded by a marshy, piney wildlife preserve with periodic gated pull-offs. Occasionally, a massive alien-looking pipeline crosses the roadway, just high enough to let tractor-trailers pass under it. Westbound, beyond the crest of a small hill, steam rises from the site’s network of uranium, plutonium, and tritium plants. A series of roadside signs display terse warnings: NO STOPPING OR STANDING FOR NEXT 17.3 MILES, and DO NOT LEAVE HIGHWAY.

There is one sanctioned place to stop midway through the complex—but only during daylight and just for a few minutes, according to the signs. The tiny park has a historical marker commemorating where Ellenton, South Carolina, once existed, before President Truman ordered the town leveled in 1950 for the nuclear site. If ever there was a place to spot a nuke trucker, this is it. Within a moment of parking our car, a red tractor-trailer with a rust-colored shipping container plows by, trailed by two dark Ford Excursions. On the truck’s door is painted “O.S.T.” It’s quickly gone. “Conducting a truck-spotting operation is a big undertaking from a personnel time standpoint,” Clements, the nuclear watchdog, had told me before I embarked on the recon.

The Ellenton marker is next to the road, so when the next truck cruises by about 20 minutes later, I snap a picture of the monument with the big rig in the background. Shortly thereafter, a tan pickup truck with government plates pulls out of the guard tower area and up to the empty intersection next to the park. The driver idles and watches us for a long moment before turning and heading up the road.

Another five miles or so west, beyond side roads leading to the 3 Rivers Solid Waste Authority complex and the Wackenhut Security headquarters, we reach the other side of the nuclear complex, and Jackson, South Carolina. Highway 125 becomes “Atomic Road” in the middle of town.

At the BP gas station on the corner of Atomic Road and Silverton Street, I ask the twentysomething cash-register attendant if she’s ever seen the nuke truckers or their rigs around town. She sheds her polite smile, giving us and our car out the window a second look. “I wouldn’t know anything about that,” she says, declining to give her name. “Here’s your receipt.”

This story had been updated since initial publication. Map production by Tasneem Raja. Sources: Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists and Federation of American Scientists (PDF), Office of the Deputy Assistant to the Secretary of Defense for Nuclear Matters, Nuclear Energy Institute, United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission, United States Navy.