Imago/ZUMAPRESS.com; Radko Keleman/ZUMAPRESS.com; Maxppp/ZUMAPRESS.com; <a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/cgeorgatou/6247883548/sizes/z/in/photostream/">Carolina Georgatou</a>/Flickr

Months before the first occupiers descended on Zuccotti Park in lower Manhattan, before the news trucks arrived and the unions endorsed, before Michael Bloomberg and Michael Moore and Kanye West made appearances, a group of artists, activists, writers, students, and organizers gathered on the fourth floor of 16 Beaver Street, an artists’ space near Wall Street, to talk about changing the world. There were New Yorkers in the room, but also Egyptians, Spaniards, Japanese, Greeks. Some had played a part in the Arab Spring uprising; others had been involved in the protests catching fire across Europe. But no one at 16 Beaver knew they were about light the fuse on a protest movement that would sweep the United States and fuel similar uprisings around the world.

The group often credited with sparking Occupy Wall Street is Adbusters, the Canadian anti-capitalist magazine that, in July, issued a call to flood lower Manhattan with 90,000 protesters. “Are you ready for a Tahrir moment?” the magazine asked. But that’s not how Occupy Wall Street sprang to life. Without that worldly group that met at 16 Beaver and later created the New York City General Assembly, there might not have been an Occupy Wall Street as we know it today.

The group included local organizers, including some from New Yorkers Against Budget Cuts, but also people who’d taken part in uprisings all over the world. That international spirit would galvanize Occupy Wall Street, connecting it with the protests in Cairo’s Tahrir Square and Madrid’s Puerta del Sol, the heart of Spain’s populist uprising. Just as a comic book about Martin Luther King Jr. and civil disobedience, translated into Arabic, taught Egyptians about the power of peaceful resistance, the lessons of Egypt, Greece, and Spain fused together in downtown Manhattan. “When you have all these people talking about what they did, it opens a world of possibility we might not have been able to imagine before,” says Marina Sitrin, a writer and activist who helped organize Occupy Wall Street.

Around 30 people showed up for those first gatherings at 16 Beaver earlier this summer, recall several people who attended. Some of them had just come from “Bloombergville,” a weeks-long encampment outside New York City Hall to protest deep budget cuts to education and other public services, and now they itched for another occupation. As the group talked politics and the battered economic landscape in the United States and abroad, a question hung in the air: “What comes next?”

Begonia S.C. and Luis M.C., a Spanish couple who attended those 16 Beaver discussions, had an idea. (They asked that their full names not be used to avoid looking like publicity seekers.) In the spring, they had returned to Spain for the protests sweeping the country in reaction to staggering unemployment, a stagnant economy, and hapless politicians. On May 15, 20,000 indignados, or the outraged, had poured into Madrid’s Puerta del Sol, transforming the grand plaza into their own version of Tahrir Square. Despite police bans against demonstrations, the plaza soon became the focal point of Spain’s social media-fueled “15-M Movement” (named for May 15th), which spread to hundreds of cities in Spain and Italy. When they returned to the United States, Begonia and Luis brought the lessons of 15-M with them. At 16 Beaver, they suggested replicating a core part of the movement in the US: the general assembly.

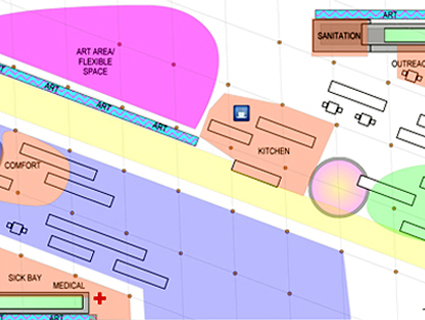

In America, we march, we chant, we protest, we picket, we sit in. But the notion of a people’s general assembly is a bit foreign. Put simply, it’s a leaderless group of people who get together to discuss pressing issues and make decisions by pure consensus. The term “horizontal” gets tossed around to describe general assemblies, which simply means there’s no hierarchy: Everyone stands on equal footing. Occupy Wall Street’s daily assemblies shape how the occupation is run, tackling issues such as cleaning the park, public safety, and keeping the kitchen running. Smaller working groups handle media relations, outreach, sanitation, and more. In Spain, general assemblies are hugely popular, forming not just in the cities but in individual neighborhoods, bringing a few hundred people together each week. In some cases, Spanish assemblies have been formed to stop home evictions or immigrant raids.

Why not bring the general assembly to Manhattan, Begonia and Luis suggested. Some said general assemblies were too time-consuming and tedious, but in the end, the idea took hold.

On August 2, the deadline for President Obama and congressional Republicans to cut a debt ceiling deal before the country tipped into default, a small group—some from 16 Beaver, others not—held a general assembly next to the iconic bronze bull in Bowling Green Park, blocks south of Wall Street. Except what was meant to be an assembly became just another rally with speakers and microphones exhorting a mostly passive crowd.

Georgia Sagri, a Greek artist based in New York who was in the crowd that day, watched with dismay. She had also supported forming an assembly, having watched them take shape back in her native Greece. Sagri was tired of the same old rally with a single focus—the death penalty, jobless benefits, immigration reform, you name it. The general assembly, on the other hand, promised a discussion without fixating on an issue or a person. In an assembly, labels or affiliations didn’t matter. There in Bowling Green Park, Sagri couldn’t wait any longer, and so she and a few others “hijacked,” in her words, the August 2 gathering, wrestling it away from your average protest and back in the direction of a real general assembly.

It took some time for the group to get the hang of it—Sitrin describes the early assemblies as “quite awkward”—but when they did the New York City General Assembly, the Big Apple’s own experiment in direct democracy, was born. When the assembly hit a snag, members would refer to a document titled “How to cook a pacific #revolution,” a how-to guide for general assemblies written by the Spanish and translated into more than a half-dozen languages. The NYCGA met on Saturdays in Tompkins Square Park in the East Village at 5:30 p.m. and lasted as long as 5 1/2 hours. Afterward, people would regroup at Odessa, Sitrin recalls, a popular diner among the activist set where, over pierogis and potato pancakes, the talk of politics and economics carried on deep into the night.

By that time, Adbusters’ rallying cry was in the air. Ricocheting around the web was the magazine’s Occupy Wall Street poster, depicting a ballerina pirouetting atop Wall Street’s charging bull, while behind her riot police emerged from the mist. Adbusters picked September 17 as its day of action. The New York City General Assembly had talked with members of Adbusters and made the decision to set its sights on the 17th as well. Buzz was forming around that date, and the NYCGA wanted to make a splash.

In other words, if Adbusters provided the inspiration, the NYCGA and other community groups provided the ground game that made Occupy Wall Street a reality. As the appointed day inched closer, the NYCGA settled on an ideal location for Occupy Wall Street: One Chase Manhattan Plaza, the former site of JPMorgan Chase’s headquarters just north of Wall Street. Then, on the eve of the big day, the New York Police Department fenced off the plaza. Organizers went back to their list of eight potential locations in Manhattan, ultimately settling on Zuccotti Park. Zuccotti wasn’t ideal, but it was close to Wall Street.

No one in the NYCGA anticipated a monthlong protest emerging out of the events of September 17. It just…happened. The occupiers really occupied. A small patch of land in the shadow of Ground Zero’s Freedom Tower was transformed into a living, breathing community. The heavy-handed tactics of the NYPD helped, attracting coverage from the TV networks and landing Occupy Wall Street on the front pages of the New York Times and New York Post. The outpouring surprised even the most seasoned activists. “The conversations we were having were about what happened on September 17th,” Sitrin says. “We never talked about what might happen three weeks after that.”

As the protest wore on, the NYCGA became Occupy Wall Street’s daily “people’s assembly,” which meets each night at 7 p.m. What’s more, the idea for an assembly, which grew out of those 16 Beaver discussions, spread to Occupy protests from Boston to Los Angeles. In the eyes of Georgia Sagri, Luis M.C., and Begonia S.C., the widespread use of assemblies here in the US connects the uprisings in America with those Europe and the Middle East like never before. “The real strength of the general assembly comes from the Arab Spring, from Tahrir Square, from Greece and from Spain,” Luis says.

Begonia adds: “The people are not here for the American economic crisis. They’re here for the crisis of the world.”

Just as in those early discussions this summer, the world has come to Occupy Wall Street. In Washington Square Park two Saturdays ago, a band of Egyptians marched through the lively crowd, the Egyptian flag dancing in the breeze. The Egyptians’ signs supported Occupy Wall Street and demanded voting rights for Egyptians living abroad. Mayssa Sultan, an Egyptian American who was among the group, says her compatriots decided to support the occupation after hearing that Occupy Wall Street had taken inspiration from the Tahrir Square revolution. “The voices being heard at Occupy Wall Street and all the other occupied cities around the country are very similar to Tahrir,” she says, “in that people who don’t have work, don’t have health care, are seeing education being pulled back, they are trying to make their voices heard.”

On Saturday, Occupy Wall Street truly went global. In 951 cities in 82 countries around the world, people marching under the banner of “October 15th” and #GlobalChange protested income inequality, corrupt politicians, and economies rigged to benefit a wealthy few at the expense of everyone else. The #GlobalChange protests were mostly peaceful, though they gave way to rioting in Rome. The same issues fueling #GlobalChange animated the thousands allied with Occupy Wall Street who, on the same day, poured into Times Square, Washington Square Park, and the streets of Manhattan, not to mention the hundreds more Occupy spin-off protests from Berkeley to Boston. It truly was a global day of action, one lifted by the momentum of those never-say-die occupiers hunkered down in Zuccotti Park, who, if not for that early group of activists thinking about the world and how to change it, might not be where they are today.