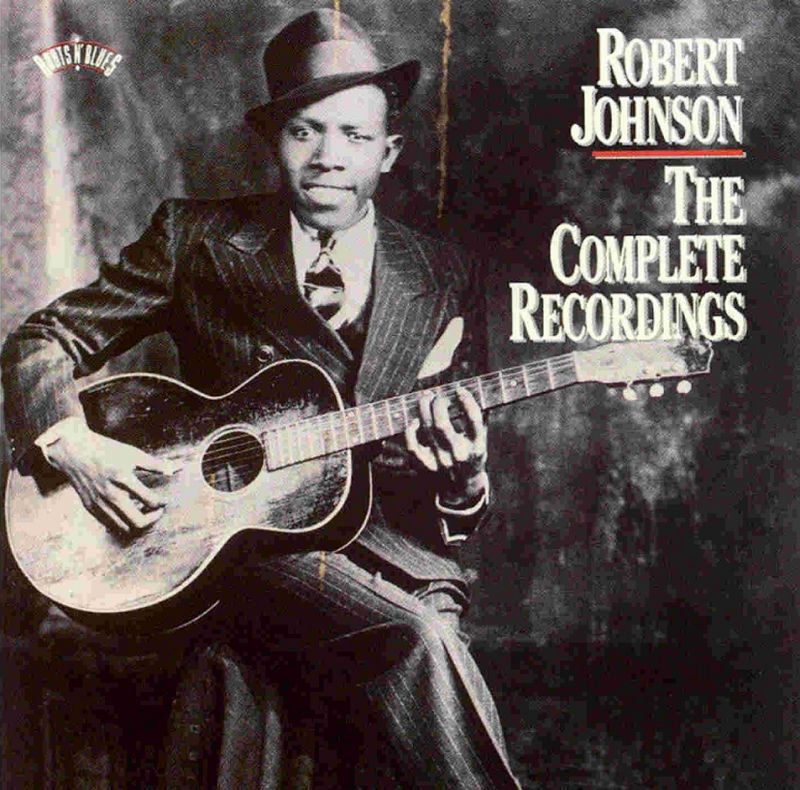

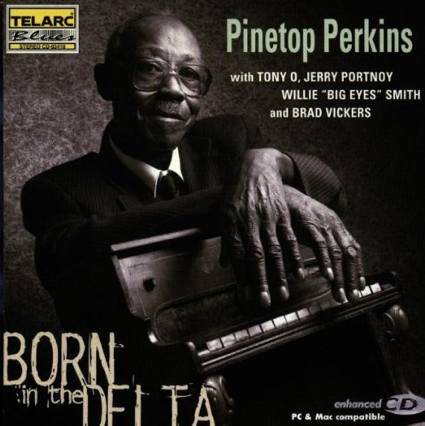

New Orleans is connected to the small city of Wyoming, Minnesota, by 1,400 miles of road known as Highway 61. The highway, which passes through Clarksdale, Mississippi, the heart of Delta blues country in the early 20th century, is central to the stories we tell today about many of the region’s musicians. It is where Robert Johnson is said to have made his deal with the devil, and where Sonny Boy Williamson II played at the King Biscuit Time radio show, the longest running American broadcast in history. Later, musicians like Muddy Waters no doubt took Highway 61 north on their way to Chicago, where they would electrify the delta sound. And this Saturday, Highway 61 will have one more claim to its title as the “Blues Highway” when 97-year-old bluesman Pinetop Perkins, who died on March 21, will be buried alongside it.

Joe Willie Perkins was born in 1913 in Belzoni, Mississippi, an hour and a half south of Clarksdale. His father, a preacher, died when he was young and at 16 he left home. Willie started out playing both guitar and piano in honkey-tonks in the late 1920s, but an injury to his left arm forced him to abandon the guitar. He began backing bluesmen on the piano and was given the name “Pinetop” because of how well he played “Pinetop’s Boogie Woogie,” a song originally written by Clarence “Pinetop” Smith. For most of his career Perkins would play as a sideman for major blues acts including Muddy Waters and BB King. Then, in the 1980s, he began performing as a solo artist. In the last years of his life, Perkins released 15 albums—and in 2005 he received a long-overdue Lifetime Achievement Award at the Grammys.

Until his death last week, Pinetop and 95-year-old bluesman David “Honeyboy” Edwards were likely the only two men alive who understood firsthand the life of a blues singer living in Mississippi in the 1930s. Pinetop was just two years younger than Robert Johnson and was playing the same time as Son House. Names like Sonny Boy Williamson and Charley Patton might sound like they are from a different era, but they were all Pinetop’s peers.

It is sometimes argued that the myths surrounding the patch of Highway 61 passing through Clarksdale—like Johnson’s deal with the devil—were not a product of the Mississippi blues culture in the 1920s and ’30s, but of white record producers trying to sell records. As many of the firsthand accounts gathered from delta bluesmen weren’t collected until after the record companies are accused of having created or exaggerated these myths, it’s hard to imagine there will ever be a definitive answer. But if the “Blues Highway” was once undeserving of its name, it won’t be when they finally lay Pinetop alongside the blacktop.