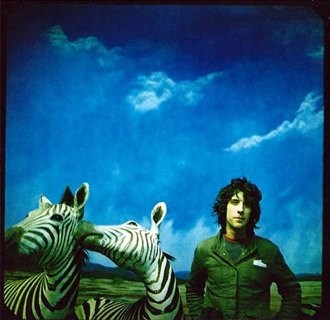

Photo by Emily Loftis

Poetry and Persian music are like needle and thread, the melody acting as a guide for the poetry’s narrative fabric. This marriage of the two art forms is ancient, and so are the instruments used. Consider the ney, a long reed-flute played by Kamran Thunder of Khayyam Ensemble, a San Francisco Bay Area group named after the Sufi poet Omar Khayyam. The instrument is believed to date back up to 5,000 years, which makes it one of the longest continually played instruments known—you’ll find in depicted on the wall of Egyptian pyramids.

Many times during Khayyam’s recent performance at Berkeley’s Freight and Salvage, the ney accompanied vocalist Aryan Rahmanian’s rendition of the great Sufi poets Rumi, Hafez, and Saadi, along with a few lyrics penned by Thunder. The tone of the seven-holed flute can oscillate between the sound of a young girl wailing and the deeper rustle of a whispered lament. The flute’s sorrow is so universally recognized that Rumi wrote about it in the revered Masnavi more than seven centuries ago (as translated by Erkan Turkman):

Listen to this Ney that is complaining

and narrating the story of separation.

Ever since they have plucked me from the reed land,

my laments have driven men and women to deep sorrow.

I want someone with a heart pierced by abandonment

so that I may tell him about the pain of my longing.

He who falls aloof from his origin

seeks an opportunity to find it again

Among those taking in the show was Goodarz Goodarzi, an Iranian who has lived in the States for 25 years. He said he appreciated the chance to reconnect with his homeland through the music and the words of the great poets. “Immigrants have nostalgia of what they have left behind. The use of Persian poetry is very precious. The combination of poetry and music is powerful.”

Vocalist Rahmanian feels similarly. “It’s very easy to mix music and poetry. All Eastern music is related to poetry. And for Persian music it’s pretty strong. It’s a very intertwined relationship.”

Indeed, poetry is central enough to Persian culture that you can even find it it Iranian pop music, like the

But Khayyam’s performance wasn’t just for Persian poetry lovers. Besides the Persian diaspora, the Freight was equally well attended by non-Iranians, many of whom knew little about Persian music. This pleased the musicians, whose goal is to expose Americans to their musical heritage. In fact, bandleader Ashkan Ghafouri founded The Tar School, an institution that aims to spead that heritage through workshops and performances. “This music doesn’t have boundaries, and we’re trying to break boundaries and reach out to other people. Music is the sound of love. It is something that can make our hearts touch each other,” Thunder said.

All five of the artists on stage, four of whom dressed in high-collared, button-down kameez adorned with red and black cashmere scarves, had gentle demeanors, but the performance was anything but reserved. Thunder’s ney bewitched the crowd with a gusty mourning, guiding in Rahmanian’s slow vocal entrance. Rahmanian sat center stage, with a black-and-red embroidered vest, his dark kinky hair haloing his head in a demanding presence. His strong structured face was focused; his eyes closed; his hands clasped over his crossed legs. But then his eyebrows knitted, joined together by a deep crease in his forehead. His voice bellowed—as if he were calling out to something beyond the audience.

In came Gharfouri and Tar School student Clark Meremeyer, with the tar and the bass Persian lute. These are waisted lutes with the quality of a banjo, but added depth from their larger size. The force of Rahmanian’s Persian-styled raga was matched with percussionist Shahin Gorgani’s tombak, or goblet drum—and daf, a large frame drum with steel bangles circling the inside. The daf is also an ancient instrument, dating back to the songs of the early Zoroastrians. Gorgani’s gaf-drumming resembles what elephants would sound like if they could dance gracefully.

The entire performance seemed almost haunting. If I could understand the Farsi lyrics, perhaps they would have matched the mysterious miasma of the hushed music hall and Rumi’s esoteric mood:

Everyone becomes friends with me according to his faculty of

perception, and many do not seek my inner secret.

My secret is not distant from my cries,

but physical eyes and ears do not possess the light (to see it).

(In fact) the body from the spirit and the spirit from the body are

not concealed, yet none (not many) are allowed to see it.

The sound of the Ney is fire and it is not the ordinary wind,

but he who does not have this fire, may he become non-existent.

It is the fire of Divine love that has entered the Ney,

it is the yearning for love that has brought the wine into action.

The Ney is friends with anyone who has been deserted,

and its musical divisions have torn off veils too.