Flickr/<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/aresauburnphotos/2678453389/">aresauburn</a> (<a href="http://www.creativecommons.org">Creative Commons</a>).

Just when liberals thought their week couldn’t get any worse, the Supreme Court decided to gut campaign finance restrictions. The Court’s 5-4 decision in Citizens United v. FEC., issued Thursday morning, opens the floodgates for unlimited corporate spending in elections. The ruling is just as bad for campaign finance reformers as they have long feared. Until Thursday, corporations and unions were prohibited from getting directly involved in elections. Now ExxonMobil can theoretically run ads urging voters to support Sarah Palin’s 2012 presidential campaign, and the AFL-CIO can run ads urging people to re-elect Barack Obama. “It’s like 100 years of precedent being overruled,” CNN’s senior legal analyst, Jeffrey Toobin, said on air shortly after the decision came out.

The decision follows the basic argument that has dogged most campaign finance laws that have faced court review: since longstanding court precedent says that corporations are legally people, deserving equal protection under the 14th Amendment, they must be accorded the right to free speech. The Court’s conservatives also believe that spending money in elections is a fundamental free speech right; thus, the government cannot restrict corporate spending in elections.

In the first paragraph of his 90-page dissent (joined in part by Sonia Sotomayor, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and Stephen Breyer), Justice John Paul Stevens accuses the conservative majority of going out of its way to “rewrite the law relating to campaign expenditures by for-profit corporations and unions.” Stevens goes on to directly challenge “the conceit that corporations must be treated identically to natural persons in the political sphere,” calling it “not only inaccurate but also inadequate to justify the Court’s disposition of this case.”

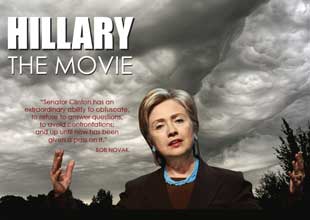

Stevens’ move to challenge the notion of corporate personhood—even indirectly—is radical. The entire edifice of American business law rests on the presumption that corporations deserve equal protection under the laws. But the majority’s decision is also groundbreaking. While it follows the contours of previous decisions, it is a far cry from the “judicial modesty” that Chief Justice John Roberts promised when he first took his place on the Court. The liberal justices on the court would almost certainly have been happy to join in a narrow decision on just the issue at hand—whether Citizens United, a political action committee, could spend its funds to televise an anti-Hillary Clinton screed, “Hillary: The Movie,” in the 30 days before last years’ primary election. The conservatives decided not to go that route. As David points out, this means that Roberts and the conservatives can no longer avoid the label of “activist” judges. They’ve turned the political system upside-down.