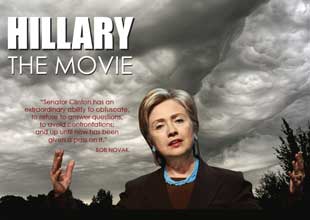

It’s hard to believe that such a bad movie could cause so much trouble. When the right-wing advocacy group Citizens United tried to distribute its 90-minute “documentary” Hillary: The Movie in January 2008, it was hoping to prevent Hillary Clinton from becoming president. In that regard, the movie was irrelevant, as Clinton didn’t make it out of the primaries alive. But the group and its film may succeed wildly in another, unintended goal: destroying any semblance of restrictions on corporate money in federal elections.

On Wednesday morning, the US Supreme Court heard arguments in Citizens United v. FEC—again—to consider whether the McCain-Feingold campaign finance law violated Citizens United’s rights to air its corporate-funded film on pay-for-view cable during the election season. It seems like a fairly simple question, and most of the justices appear to agree that the government has no business preventing Americans from watching Citizens United’s dreadful movie. But the law is rarely that simple. Instead of sticking with the issues presented by Citizens United during arguments before the court in March, the justices asked the parties to re-argue issues not raised in the initial litigation, such as: do corporations have a free speech right to spend unlimited amounts of money on advertising to support or oppose a political candidate?

For nearly a hundred years, the answer to that question has been no. Corporations cannot pour money without restrictions into political races. But the Roberts court looks as if it is chomping at the bit not just to undo those limits (and potentially open up the floodgates for corporate political money) but to deal yet another blow to members of Congress, whose work it has regarded with disdain. In previous cases, this court has often refused to acknowledge thousands of pages of legislative record that in the past would have usually given the justices pause before trampling the work-product of the democratic process. That hostility imbues the Citizens United case, with Chief Justice John Roberts as its most prominent source.

The last time the court considered similar campaign finance issues, Roberts voted to uphold the old precedents and generally to preserve federal bans on corporate spending in elections. But during Wednesday’s arguments in Citizens United, he looked ready for a change. He dominated the questioning of President Obama’s new Solicitor General, Elena Kagan, who made her first argument at the court, representing the Federal Election Commission (Kagan wore a black suit, ending speculation about whether the first woman to hold the job would appear in the SG’s traditional morning coat). Roberts and Kagan sparred over whether bans on corporate campaign contributions served a compelling public interest. Kagan argued the value of protecting corporate shareholders from having their money used for unapproved political purposes. Roberts suggested that shareholders were smart enough that they didn’t need the government to protect them; Kagan smartly replied that she herself had trouble keeping track of her corporate investments, a problem most Americans with mutual funds suffer from.

Roberts’ corporate defense was dramatically challenged by the court’s newest member. Making her debut, Justice Sonia Sotomayor quickly proved that there’s a lot more fire to her than is evident in her pedestrian written opinions. She jumped into the fray with pointed questions that were almost shockingly liberal, in stark contrast to her muted performance during this summer’s confirmation hearings. In one instance, she made the surprising suggestion that the problems in this case had arisen because the court had previously erred in imbuing a corporation with human characteristics and granting it rights equal to those of individuals. Along with Justice Stephen Breyer, a former staffer to the late Ted Kennedy, Sotomayor mounted a passionate defense of the legislative process. This suggested a respect for Congress that contrasted with the sentiments of several of her fellow justices, who seemed to agree with attorney Ted Olson’s argument that “you always have to second-guess Congress when it comes to the First Amendment.” Sotomayor asked whether, if the court struck down the McCain-Feingold provisions that were crafted through many years of congressional deliberations, “would we be cutting off that future democratic process?”

Sotomayor’s spunky performance foreshadowed future fireworks between her and Justice Antonin Scalia. While Sotomayor was questioning the wisdom of treating corporations like people, the conservative icon countered with the concerns of the “local hairdresser,” a single-share corporation that he seemed to believe was most at risk of having its free speech rights violated by McCain Feingold. Scalia repeatedly insisted that most corporations are mom-and-pop operations rather than the “mega-corporations” described by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who noted that many of the corporations restricted by McCain-Feingold were comprised largely of foreign investors. Returning to his hairdresser, Scalia thundered, “There is no distinction between the individual interest and the corporate interest….Yet this law freezes all of them out.”

Despite arguments over the nature of corporations, it was clear that many of the justices were struggling to find an acceptable way to accommodate the likes of Hillary: the Movie without completely gutting a century of court precedent. Justice John Paul Stevens often sounded like the president appealing to Republican moderates for a Third Way.

Perhaps the most persuasive argument against blowing up McCain-Feingold and its predecessors came from attorney Seth Waxman, representing Sen. John McCain. He finished the hearing by noting that no corporation had ever actually challenged the campaign finance law. Waxman’s poignant observation spoke volumes about the chief justice, who seemed to be crusading for corporate rights that even corporations themselves haven’t been seeking.

A decision in this case could come by the end of the year.