Vdovichenko Denis/Shutterstock

In the wee hours of Wednesday morning, University of Missouri police arrested 19-year-old Hunter M. Park for “making a terrorist threat” on the anonymous messaging app Yik Yak. And later that morning, in a separate incident, police nabbed Connor Stottlemyre, a freshman at Northwest Missouri State University, in connection to a message he allegedly posted on the site: “I’m gonna shoot any black people tomorrow, so be ready.”

Just two days earlier, amid protests over racial inequality at the University of Missouri, “Yakkers” on and around campus took to the app’s hyperlocal message boards to debate the resignations of university president Tim Wolfe and chancellor R. Bowen Loftin and question whether the protests did more harm than good. As the threats of harming black students allegedly linked to Park and Stottlemyre surfaced, concern spread throughout the University of Missouri, Columbia campus. Once bustling spaces were left empty as many students stayed home.

So what exactly is Yik Yak, the app at the center of these cases? Here’s what you need to know:

What is Yik Yak? Yik Yak is a bulletin board-style, location-based social network where users can anonymously post messages to anyone within a five-mile radius. The app, founded in 2013 by two recent college graduates, was meant to be “a place where communities share news, crack jokes, ask questions, offer support, and build camaraderie,” cofounder Brooks Buffington explained in a blog post on Wednesday. The site is limited to users who are 17 or older and has become especially popular on college campuses. The company has built “geofences” to block the app’s use around elementary, middle, and high schools.

In theory, the app operates as a self-policing community. As on sites like Reddit, Yakkers can upvote comments they like and vote down comments they don’t making it harder for them to be seen. Yet the seemingly innocuous banter can devolve into a cesspool of crude and demeaning remarks, blurring the line between free speech and online bullying.

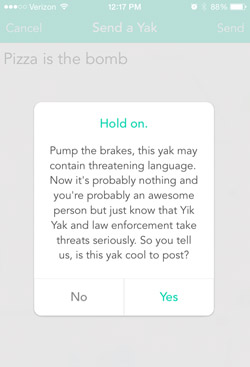

If message contains threatening (but not necessarily racist or abusive) language, the app is supposed to detect it. A pop-up will warn about the consequences of posting that message. “You’re probably an awesome person but just know that Yik Yak and law enforcement take threats seriously,” reads one warning screen. Critics say that these pop-ups are not enough to curb abuse on the social network.

Is it really anonymous? It’s unclear how exactly university police linked Park to the anonymous posts, but a Yik Yak spokesperson confirmed to Mother Jones that authorities need a subpoena to obtain user information unless “a post poses a risk of imminent harm.” That’s what happened three weeks ago, when Texas A&M police obtained an emergency subpoena to arrest and charge Christopher Louis Bolanos-Garza for posting a threat on Yik Yak.

“Yik Yak cooperates with law enforcement and works alongside local authorities to help with investigations,” a Yik Yak spokesman said in a statement. After submitting a detailed request to Yik Yak, authorities can obtain information such as a “user’s IP address, GPS coordinates, message timestamps, telephone number, user-agent string, and/or the contents of other messages from the user’s posting history,” according to the site’s legal provisions. Yik Yak handles these on a “case-by-case basis.”

The company’s statement also says that it “may provide information without a subpoena, warrant, or court order when a post poses a risk of imminent harm.”

What constitutes an imminent threat on Yik Yak? The company may disclose user information to authorities “when we believe that doing so is necessary to prevent death or serious physical harm to someone,” according to its legal fine print. These provisions highlight examples of imminent dangers that include bomb threats, kidnapping, school shootings, or suicide threats. Yakkers can also flag and report posts and file complaints with the company.

In Park’s case, university police received numerous complaints from people about his alleged threat, though it’s unclear if it had been flagged by Yik Yak.

What kinds of problems have cropped up on Yik Yak elsewhere? At colleges and universities throughout the country, threats of mass shootings, racially charged commentary, sexually explicit comments, and even a sex tape have cropped up on the network. The Washington Post has a list of incidents here. The Post reports that at least a dozen universities have tried to banish the app by blocking access to it on campus wi-fi. In May, after seven students filed complaints about feeling threatened on the app, the College of Idaho tried to ban Yik Yak and asked the company to build a geofence around the campus. Yik Yak declined to do so.

What’s next for Yik Yak? Pressure is mounting on the company to step up its efforts to curb harassment and threats. In October, a coalition of 72 feminist and civil rights groups urged the Department of Education to issue guidelines that protect “students from harassment and threats based on sex, race, color, or national origin” on Yik Yak and other anonymous social media platforms. The coalition told the Post they would send a letter to the app’s Silicon Valley investors, urging them to strengthen the company’s policies to combat “hateful targeting and harassment of students on college campuses.”

Buffington, Yik Yak’s cofounder, emphasized in his blog post about the events at the University of Missouri, “Let’s not waste any words here: This sort of misbehavior is NOT what Yik Yak is to be used for. Period.” Part of the Yakker herd, he wrote, means respecting one another: “At its core, Yik Yak is your community; it’s an extension of the real world directly around you.” And like the real world, Yik Yak can get pretty messy.