Rather than offer a narrow list of my own favorite photobooks of the year—lots of documentary and street photography—I turned to some of the awesome photographers who contribute to Mother Jones and asked what caught their eye. The result is this diverse list of great books, a number of which I totally missed and am now scrambling to find. Also contributing to our picks is Jeremy Lybarger, who works on the admin side of Mother Jones but consistently knocks out smart photobook reviews.

It’s worth noting that Carolyn Drake‘s gorgeous Two Rivers proved to be an all around favorite. I included it among my favorites, as did three of the photographers we asked. It’s a beautiful, smart photobook.

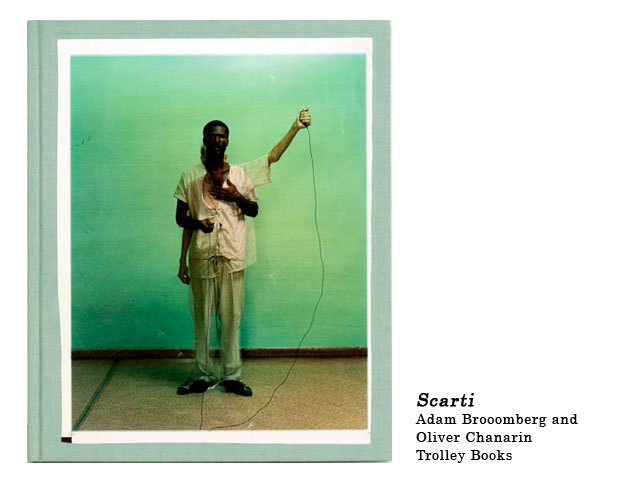

Ten years ago, the dynamic photographic team of Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin published Ghetto, their journey through 12 contemporary gated communities. It is now out of print—if you can find a copy, it will be at least 10 times the original price.

While printing the book, then Trolley Books publisher and creative genius Gigi Giannuzzi, kept the scarti—that’s Italian for “scraps.” Scarti is the paper fed through the printing press to clean the ink drums between runs. Normally these byproducts are thrown away, but Giannuzzi kept them, and they were discovered after his death from cancer last year.

In these scraps, we see a mash-up of the original Ghetto images layered atop one another in combinations and textures, which appear as double exposures and create new meanings in mesmerizing and unexpected ways.

Reviving a photographic classic in this original and astounding way makes Scarti one of the most exciting photo books of the year for me. That this creation was somehow sealed in the mind of a publisher when he picked up scraps from a printing-room floor a decade ago is more than publishing, it’s photographic alchemy. —Contributing photographer Nina Berman (“It Was Kind of Like Slavery,” March/April 2014 print issue)

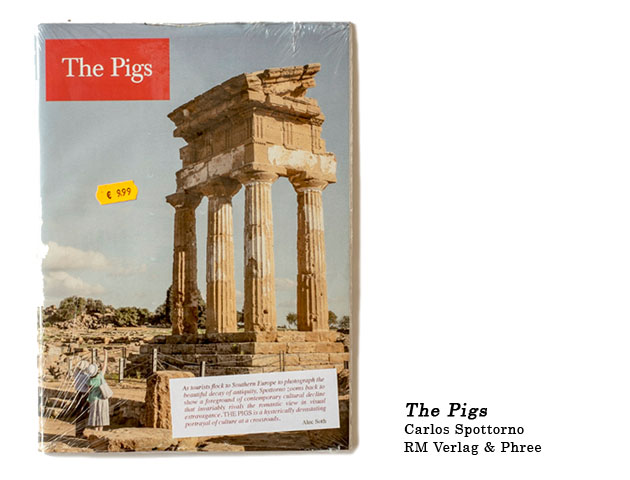

The Pigs, by Carlos Spottorno, isn’t a proper book. It’s a magazine, made to imitate The Economist after that mag used that acronym for Portugal, Italy, Greece, and Spain in reference to their recent economic woes. The fonts, logo, paper, and layout of The PIGS match The Economist‘s—there’s even a fake ad on the back cover. The idea is smart and the photos hyperbolic, an exaggerated showing of the region’s poverty meant to poke fun at over-the-top media coverage. The photos themselves aren’t amazing, but that’s actually one of the book’s strongest points. Spottorno seems more interested in creating a unique document than in having us “ooo and ahh” over his photographs, and I find that admirable. —Peter DiCampo (“Robert Davidson’s Creative Spirit“)

Carolyn Drake’s Two Rivers is one of the more unique objects I’ve acquired this year. The photographs are, of course, beautiful. Stunningly so. After years of having seen her work on computer monitors, I decided that a book would probably be as close as I could come to owning any of her work and being able to spend time with it. Its design, while creative, doesn’t allow for a satisfactory viewing of the images. It shows that everything is connected, and that one image leads to another, though each is truncated in some way, so it feels like the sequences within the book never quite reach a climax. It was a bold risk, but one that ultimately pays off as she reshapes her work for this outlet. —Contributing photographer Matt Eich (“Inside Mississippi’s Last Abortion Clinic“)

Two Rivers is remarkable both in content and design. The truncated images add a lyrical kind of tension to imagery that is beautiful, honest, and revealing of a region rarely seen. Like the sea the two rivers spill into, this book invites you in and intoxicates you and all the while you’ve forgotten you’re holding a book. —Contributing photographer Lana Slezic (“Hidden Half: Women in Afghanistan“)

I love everything about Two Rivers: the painterly, atmospheric images, the sequencing, the overlapping of images from page to page, and the Japanese binding. This book has life—dare I say a soul? It breathes. And I feel like I’m having a conversation that’s almost familiar, although not at all. Perhaps that’s because of Drake’s deep, nuanced understanding of the people and places she’s photographing. Adding to all of this, the book feels like something truly special, an amazing blend of craft and concept as if as much thought went into the delivery of these images as into the photographs themselves. —Tristan Spinski (“One Weird Trick to Fix Farms Forever“)

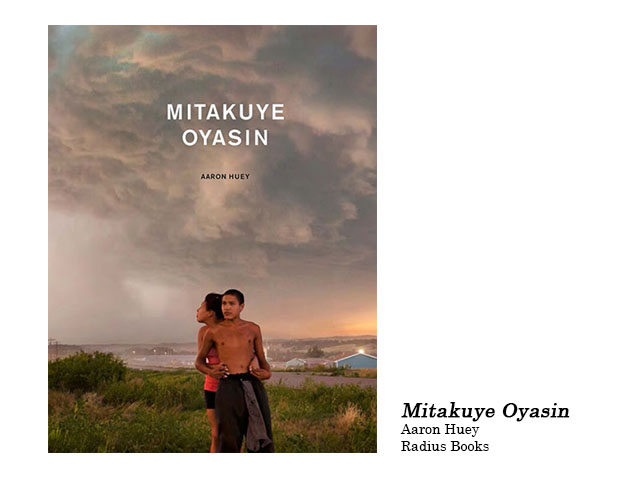

Our favorite book of 2013 is Mitakuye Oyasin, by Aaron Huey. It’s page after page of visual poetry. Many photographers have shot the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, but none with the same intimacy as Huey has, or for a comparable duration. This is more than evident in his photos. They are full of color, life, and moments. He brings us deep into a community, with great respect for the people he is photographing. Most importantly, Huey’s work makes you care about the people and the place—not an easy task in our visually savvy world. Despite its size (208 pages) his book is full of images that leave you wanting another. —Jenn Ackerman and Tim Gruber (“Too Old For Prison?” “Wellstone’s Revenge“)

Instead of the best photography books of 2013, I chose the only photography books I purchased this year. I love them dearly, but don’t think they necessarily qualify as the best. Joseph Cornell’s, Manual of Marvels was published by Thames and Hudson in late 2012. I just bought it a few weeks ago and so I am just going to pretend as though it was published this year. When it arrived, I found myself painfully disinterested in the faux-wooden box packaging. It’s awful. But once I opened the box and dug out the 60-page facsimile of Cornell’s Untitled Book Object: Journal d’Agriculture Pratique et Journal de l’Agriculture, I was lost in a fantastical world of drawings, handwritten, and typewritten text, cut-outs, cut-ups, cut-ins, illustrations, colored paper inserts, transparent overlays, diagrams and photomontages. The facsimile is accompanied by a CD that includes a digital copy of all 844 pages with extensive footnotes that help decode the densely layered assemblages. There is also a softbound book with four essays that I hope to get to someday. —Stacy Kranitz (“Chasing Meth in Laurel County“)

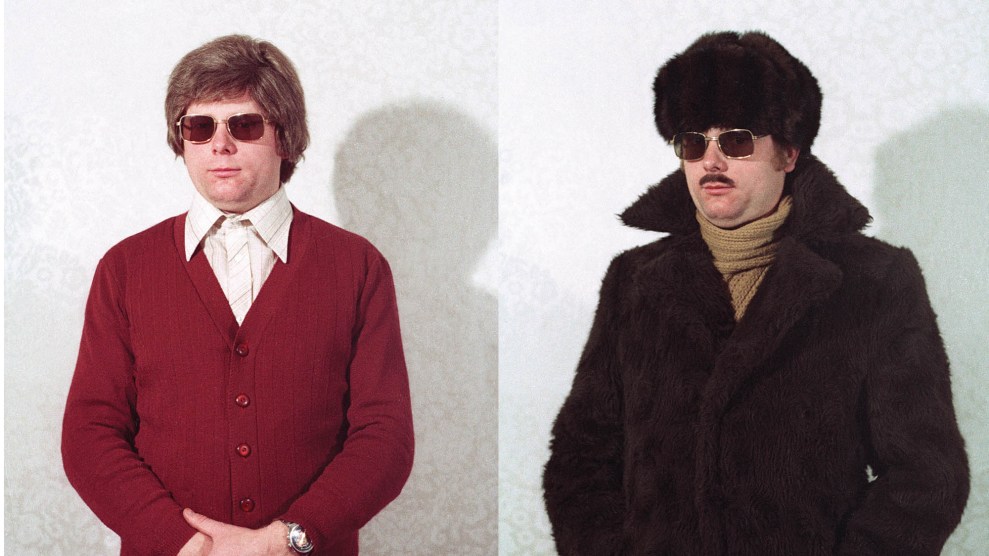

Boris Mikhailov’s Bücher/Books offers a beautiful replication of two previously unpublished maquettes: Structures of Madness, or Why Shepherds Living in the Mountains Often Go Crazy and Photomania in Crimea. It’s maybe not the best Mikhailov book—he has made more than 40, after all—but that doesn’t matter because his work is a constant source of inspiration for me. The first book within the book juxtaposes rough drawings and sketches with craggy rock formations—the forms of each medium overlap in so many pleasurable ways. The second book is comprised of a series of playful, weird, disturbing, and erotic black-and-white images from a trip to the beach. Wedged between the two books are several essays, but the one most worth reading is by Boris and his wife, Vita. It’s beautiful and poetic and ties together the themes of the two books. I had my eye on many books this year. Unfortunately, I also had very little money. So I also wanted to mention two other books that I wish I owned. I think I would have really liked them and hope to one day possess them: Guillaume Simoneau’s Love and War (see below) and Paul Kwiatkowski’s

And Everyday Was Overcast. —Stacy Kranitz

One of the frequently overlooked, and most powerful qualities of the photograph is its ability to reveal the most intimate and personal moments of lives and careers that are so often blurred into anonymity by the steady barrage of headlines in today’s 24-hour news cycle. The best photographs are the ones that allow us to forget ourselves and our surroundings and to be taken on a journey to a world that has been carefully crafted in a selection of fractions of a second—the brief moments of everyday life the photographer has allowed to pass through an open shutter, and then chosen to share with us.

With all of the news stories to follow and all of the photobooks to look through this past year, Guillaume Simoneau’s Love and War and Ben Schonberger’s Beautiful Pig are two of the best, and I am hard pressed to find a better example of the poetry that results in the convergence of art and long form journalism. Love and War offers a glimpse into the personal lives of the selfless and nameless American soldiers fighting abroad, while Beautiful Pig honor the memories and personal archives of Detroit’s unsung public-sector heroes, revealing the faces and identities of the pension-holders who devoted their careers to the impossible job of holding up the pillars of law and order in a crumbling city. Simoneau and Schonberger have provided some of the year’s best visual storytelling. They remind us of the power of the photograph, and its ability to tell a story, open the doors of empathy, allow us to make sense of the unknown, and see ourselves in the lives of strangers. We just have to look. —Will Steacy (“This Newsman Ink That Runs Through My Veins“)

First published in 1980, Seiji Kurata‘s Flash Up is a seminal Japanese photobook and something of a fetish object; used copies often fetch $1,000 or more online. This new slip-cased edition from Tokyo-based Zen Foto Gallery is still pricey ($154 plus shipping) and very limited (750 copies), but it’s a comparative bargain. Kurata studied with Daido Moriyama, and while his work shares a similar high-contrast aesthetic, it also takes a more traditional documentary approach. Kurata basically ricocheted around Tokyo at night, shooting flash-lit portraits of yakuza gangsters, tattooists, transvestites, strippers, samurai, Hells Angels, club-goers, car wrecks, and the various nightwalkers in the Shinjuku vice district. Like any great photobook, Flash Up is a dozen things at once—sleazy, lurid, beautiful, witty, clear-eyed, cold-hearted, tender. —Jeremy Lybarger

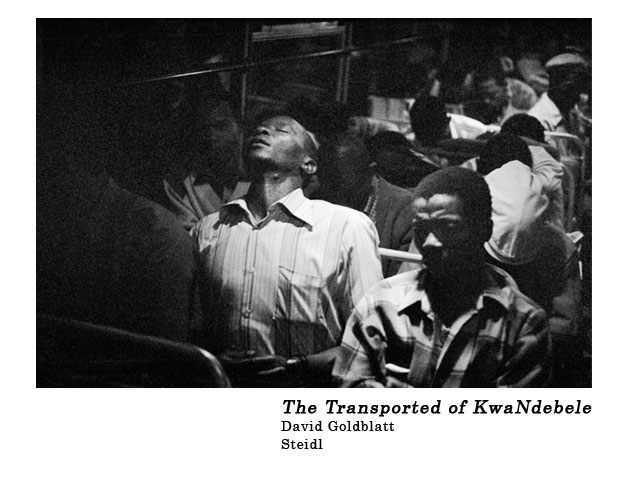

David Goldblatt is one of the world’s great photographers and, arguably, the greatest ever from South Africa. Apartheid is the great moral theme of his work, but it’s only part of a deeper reckoning of the varieties of human suffering and grace. The Transported of KwaNdebele, first published in 1989 and newly reissued in an expanded edition, is a testament to Goldblatt’s unerring vision. The book chronicles the grueling bus ride that workers from KwaNdebele, a semi-independent homeland for poor blacks, took to their jobs in the factories and mines of Pretoria—a roughly 75-mile journey that began well before dawn. Goldblatt’s compositions are immaculate, even when he’s cramped in bus aisles or alongside highways at 5 a.m. There are scenes here—expressions of pain or exhaustion, certain tones of light—that cut to the bone. —Jeremy Lybarger

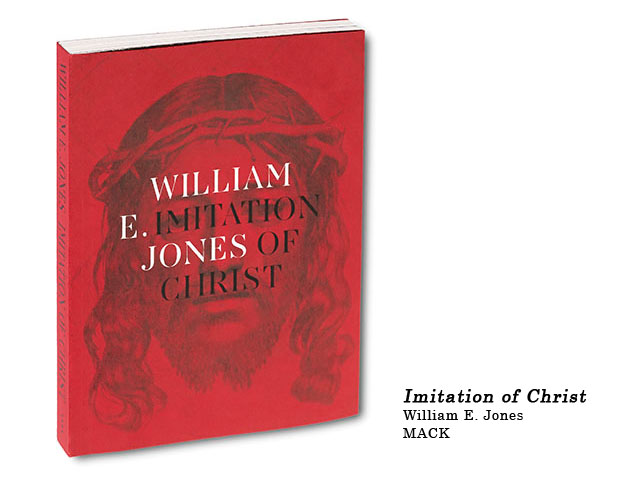

Imitation of Christ by William E. Jones is not, strictly speaking, a photobook. It’s more like an illustrated essay inspired by Pedro Meyer’s photograph of a wounded Nicaraguan soldier. Jones first conceived the project as an exhibition at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, using source material from the Hammer’s archives. His selection of 45 images—everything from contemporary Latin American art to photojournalism to Baroque and Renaissance prints—explores the knotty relationship between salvation and revolution. His text excavates the social, psychological, historical, and sexual subtexts of Pedro Meyer’s photo, offering a vivid riff on the possibilities of trauma. —Jeremy Lybarger

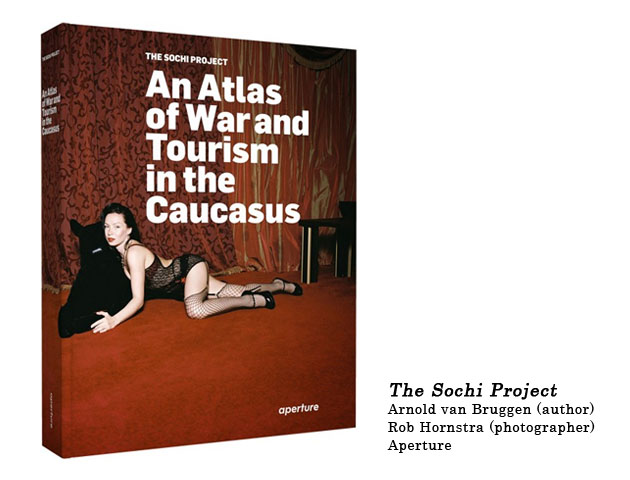

I haven’t been able to pore over the stacks of photobooks released this year—something I really enjoy—but I have come across a few I particularly liked. Among them is The Sochi Project: An Atlas of War and Tourism in the Caucuses. I tend to gravitate toward photography that blends art and sociology and serves as a means of understanding people and culture. That’s the approach taken here by Arnold van Bruggen (author) and Rob Hornstra (photographer). The book, with its idiosyncratic portraits and landscapes, is an invitation into a world unlike my own—and one that may change dramatically when it hosts the 2014 Winter Olympics. —Gregg Segal (“How Dr. Bronner’s Got All Lathered Up About GMOs“)

For a lighthearted twist in documentary photography, I recommend Life’s a Beach by Martin Parr. In this new, colorful and compact edition, Parr gives us a fun look on the globally shared ritual of beachgoing. The documentary images bypass conventional mechanisms of classification and can clearly be understood as a record of behavior. He studies human nature in public places where all have chosen to be vulnerable—a range of absurd moments and interesting characters and sometimes snapshots recording life where the sand and water meet. A nice feature of the book is that its bright cover art and compact size makes it good for sharing at the beach. —Ben Sklar (“Meet Ted Cruz,” “Fracking’s Latest Scandal“)

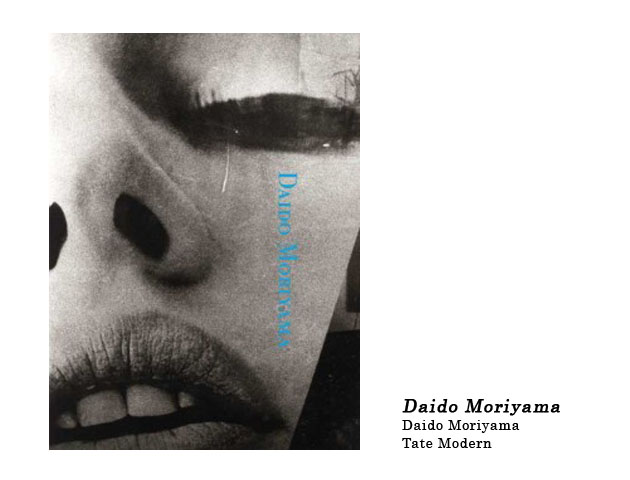

I’d also recommend Daido Moriyama’s self-titled book published by the Tate Modern for a look at daily life, rituals, or personal visual interests that bring a viewer closer to the artist presenting the images. Moriyama’s quick, almost impulsive or reactionary style of point-and-shoot, black-and-white photography shares an unusual vision with the world, and enables viewers to answer their own questions about the work. The high-contrast printing and seemingly random sequence of images bring readers closer to the inner working of the artist, and a greater understanding of a familiar world often overlooked. —Ben Sklar

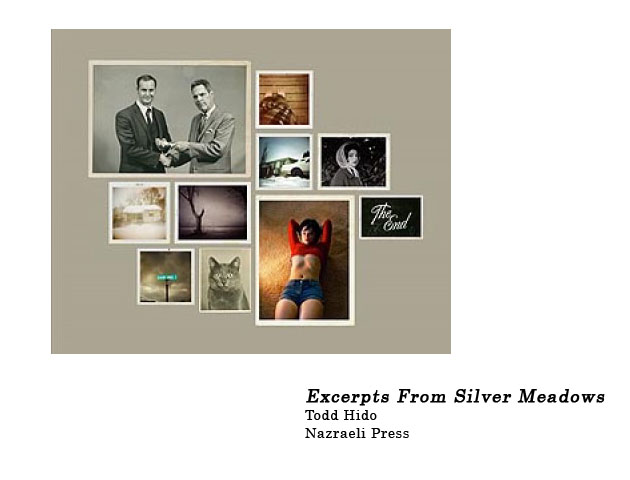

The American Midwest seems a place to run from. It’s also the place (his childhood home) that informs Todd Hido‘s latest book, Excerpts From Silver Meadows. Part reflection, part fiction, part document, it is formed in the murky waters of memory, the photographs existing in the ambiguity also embraced by the likes of Anders Petersen or Takuma Nakahira.

Landscapes that appear throughout the book seem devoid of life, lost in haze and nothingness—the visual equivalent of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, and a place to protect one’s children from, till death. The book’s many portraits bring to view characters that live on the fringes of society, damaged souls that seem lost and mistreated. There are numerous found and archival photographs, which are heightened by the tension of the unknown. Exteriors, as in Hido’s previous work, bring out the desire to see behind drawn curtains, an unsettling emotion that pollutes us all. Beautifully produced and printed, Excerpts… is an honest book that reveals much, but mostly poses questions. —Contributing photographer Danny Wilcox Frazier (“Eulogy For Detroit,” “End of the Line,” “Out of Iowa“)

There is a melancholy and looseness to Todd Hido’s images that make me feel like I’m looking at dreams and memories. And there’s a seduction and rawness to his work that makes me blush a bit. I love looking at it, and feel a bit guilty about it at the same time. Hido created a large book or gorgeous big prints, making it so easy and wonderful to get lost in. —Tristan Spinski

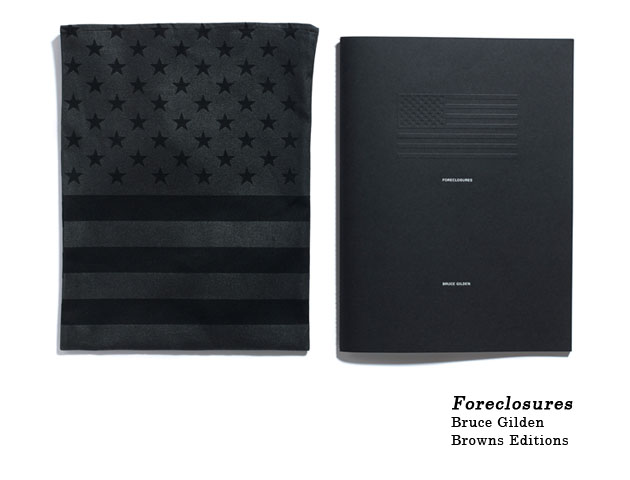

Fort Myers: Broken dreams in the land of the sun. Detroit: The place America’s middle-class crumbles into piles of rubble goes up in flame at the hand of inequity and desperation. Out West: It’s bigger and better. Not too big to fail though. Monuments of Wall Street greed are left like tombstones across this desolate landscape. Auction, lender, ghost…

Amid all this desolation, beauty resides, and each photograph of Bruce Gilden’s Foreclosures conveys the tension of picturesque destruction.

Economists Emmanuel Saez and Thomas Piketty have documented the inequity of wealth in America over the past decade. The new Gilded Age is most exemplified in post-recession income gains. While the middle class has seen almost no recovery from losses during the recession, the top 1 percent has captured most of the nation’s income gains since the recession’s end. The results are presented in Foreclosures. As always, the photographs reflect Gilden’s unflinching approach. —Danny Wilcox Frazier

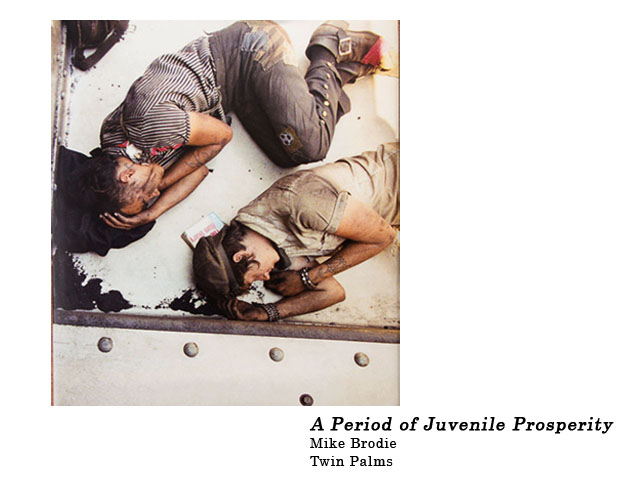

A lot of photographers, including me, have thought of doing a photo story about train hopping. The problem is, 99 percent of us could only ever be tourists. We don’t really understand what it means to live the lifestyle that surrounds the act of catching a ride on a freight train. According to his hauntingly poetic words in the final pages of A Period of Juvenile Prosperity, that lifestyle not only came naturally to Mike Brodie, it formed him into the man he is today.

The American Dream failed Brodie in a dramatic way, just as it has failed countless others. He responded by choosing to explore the fringes of society, and live life simply for the sake of living. His photos show us how grit and danger are intimately entwined with experience and wonder. His photography seems to be more of a visceral reaction to his emotions than a calculated process. This raw urgency and Brodie’s ever-present personal connection to the book’s subjects makes it exceptionally powerful.

When the book first came out, the photography world seemed to ignite for Brodie. He was the instant darling of an industry he apparently wanted nothing to do with. As his train-hopping days came to an end, so did his photography practice. He went on to start his own business, running a mobile diesel engine repair shop, quietly retreating from his prolific contribution to the world of photography. While that may seem crazy to some people, it makes a whole lot of sense for someone who truly lives on his own terms. —Ian Willms

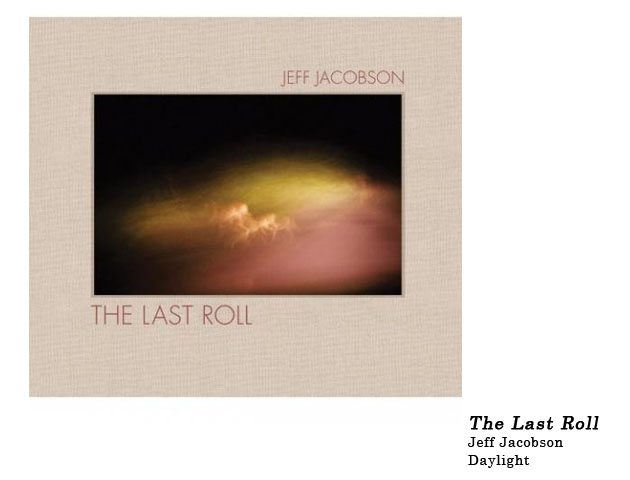

The Last Roll by Jeff Jacobson is a favorite, not just for the beauty and complexity of image, but also for the honest recognition of uncertainty and existence. —Danny Wilcox Frazier

For what it’s worth, most of the photobooks I really liked this year, I wrote about over the past 12 months: Garry Winogrand’s exceptionally awesome retrospective, AP’s photo history of the Vietnam War and Michael Kamber’s exceptional Photojournalists on War, and Joshua Lutz’s Hesitating Beauty. Hard Art, Lucian Perkins‘ look at the early DC punk scene definitely hit a sweet spot for me. Rian Dundon‘s Changsha remains difficult to get, tied up in a messy legal battle, but it’s worth the effort to track down.

Then there were books I never got around to reviewing: Rena Effendi‘s Liquid Land, Robin Hammond‘s double-fisted knockouts: the haunting Condemned and his gorgeous Zimbabwe book. Contributing photographer Chris Buck‘s debut, Presence, surpassed all of our expectations (which were pretty high). Straddling the increasingly blurred line between zine and book and promo, Benjamin Rasumussin‘s Home and the first installment of Matt Eich‘s Seven Cities let those two editorial photographers stretch their legs on personal projects. Nic Dunlop’s dogged coverage of Burma/Myanmar for years resulted in his beautiful book Brave New Burma. And on a tip from another best-of-photobook list, I just picked up Kursat Bayhan’s Away From Home. Recommended by Jason Eskanazi, it echoes the look and feel of Eskanazi own 2008 masterpiece, Wonderland. —Photo editor Mark Murrmann