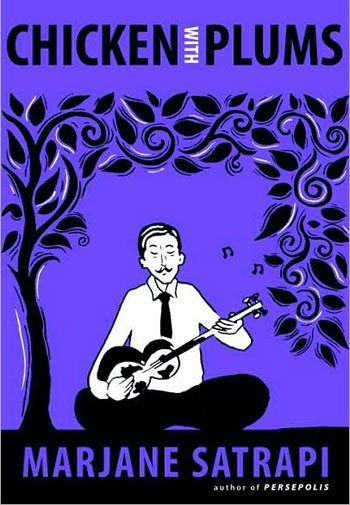

Marjane Satrapi

Opening Friday, the live-action film adaptation of Marjane Satrapi’s graphic novel Chicken With Plums tells the story of Nasser-Ali Khan, a master violinist so heartbroken by his unattainable love, Irane, that he decides to stay in bed and wait for death to come and claim him. Codirected by Satrapi and French comic artist Vincent Paronnaud, it’s an artfully rendered romanti-tragic fantasy full of dark humor and surreal tangents—think Woody Allen and Jean-Pierre Jeunet (Amélie, The City of Lost Children). But the story doubles as an allegory of lost homeland for Satrapi, whose debut, Persepolis, told of her upbringing in (and eventual flight to Paris from) Iran and its increasingly repressive regimes. During 2010’s post-election uprising in Tehran, she says, “I was just in front of my computer crying day in and day out”—over the flight of democracy from Iran and her distant hope that it might one day return. During a rare break between cigarettes at her San Francisco hotel suite, the multitalented Satrapi ruminated on everything from the futility of war to Janet Jackson’s “cute” nipple. Watch the trailer below, and then we’ll proceed to the interview.

Mother Jones: Persepolis was mostly autobiographical. Chicken with Plums is mostly fictional. Which story was harder to tell?

Marjane Satrapi: Persepolis. I had to remember many things that were extremely painful. Seeing my grandmother, who is dead, even in animation, walking—it’s really something. So from a psychological point of view it was much more difficult to make Persepolis. And it takes much longer. You have to be resistant.

MJ: In Chicken With Plums, the unattainable love of Nasser-Ali, your protagonist, is named Irane. Is that a reflection of your feelings toward your homeland?

MS: It is not by coincidence. In the ’50s the whole of the democracy flew from my country because of the American-British coup d’état against [Mohammad] Mosaddegh. Irane is actually a real name; it’s like being called France in France. It’s an allegory—the thing that you wanted the most that is lost. And then we have a second layer that is actually very realistic: a guy who is depressed who decides to die. You don’t have any notion of redemption. He does not like his kids at the beginning; he does not like them more at the end. Today, in all the films, all the parents they love their kids. But somebody has to explain to me where do they come from, all these miserable kids who later on will become miserable adults? So some kids are not loved by their parents. And you don’t have good or bad people. Each person has his moment of glory. But that is a boring story. How to make it interesting is to have this person die at the beginning—so to be able to use the death to celebrate his life for 1 hour and 22 minutes.

MJ: Over the past few years, Iran has undergone all kinds of turmoil—notably the post-election protests. What was going through your mind at that time?

MS: What was extremely interesting to me in this revolution was we had as many women as men—it was women and men hand-in-hand. And that shows a big change. When you say revolution when you have only men outside, you know that something is going wrong. I’m not like a hardcore feminist, but I think that one of the things that makes the society advanced is equality between men and women. If half of the society is oppressed by the other half, it’s not fine. You cannot go towards democracy because you don’t use half of your intellectual, scientific, artistic, whatever, forces. So it’s an evolution that has happened in Iran. That gives me hope, because changes never come by the revolutions. Revolutions just spread blood. Evolution—this is something that changes in the long term. Because history is long term. But today, we don’t talk about history. The past is two weeks ago, and the future is two weeks after.

MJ: Two minutes!

MS: Even two minutes. I mean, I have not seen one politician today that has a vision for the 10 coming years, for the 20 coming years. It’s today we want to win the election. It’s for today, for today, for today.

MJ: Speaking of elections, over the past six months our Republican presidential candidates have been walking suggesting the US should attack Iran. Does this worry you?

MS: It doesn’t worry me because they have already messed up one war in Iraq, and Afghanistan is not very good either, so, you know, there is no more money. If there was not the background of Afghanistan and Iraq, I would be very much worried.

MJ: It’s just that the recent rhetoric is so similar to pre-Iraq. In the book, Nasser-Ali plays the tar. Knopf Doubleday

In the book, Nasser-Ali plays the tar. Knopf Doubleday

MS: Absolutely. But they must be idiots if they do that. You just have to see the changes that they did in Iraq. And Iran is not Iraq. Iraq was an exiled country; it was completely destroyed. Iran is a much bigger country. It’s completely stupid—I mean, someone has to tell me when in the life of the human being has war solved the problem, that we should continue making wars.

MJ: I gather you still have relatives in Iran.

MS: My parents, for example.

MJ: Both Persepolis and Chicken With Plums portray relatives of yours. What do they think of your work?

MS: Well, when I’m nice to people I always use their real name and when I’m not nice to them, it’s not them—I mean, nobody will know that’s them. As for the second story, really the only truth about it is that I saw a picture of my mother’s uncle and they told me that he was a great musician. That when he was playing in his garden they would stop in the street listening to his music. And I saw some sort of melancholy and something in his eyes. And that was really a moment in my life that I had all these questions and I was completely obsessed by the idea of death. So I chose this story, but then the rest is my story—things that I have heard, things that I have made up. I think that all stories—if you make movies about zombies and aliens—it has always to do with your personal story. If not directly, it is about your fears, your obsessions, things like that.

MJ: So in short, your relatives dig your stuff?

MS: Yeah, they do.

MJ: But the Iranian regime does not dig your stuff. Didn’t they try to ban Persepolis?

MS: Yes. It was part of the black market. But you know, everything else is part of the black market. Listen, I buy books of Iranian crosswords in a shop in Paris because I love to do crosswords, okay? You have this crossword with the image of an actor and you have to know everything [about him]. These crossword journals are official, because everything goes through censorship in Iran. Nothing of Brad Pitt is shown in the cinema, and here you have a photo of Brad Pitt and you have to know the name of his first wife, second wife—that means that officially they know that everybody sees all the films of Brad Pitt.

MJ: It’s like they’re inviting you to be subversive.

MS: In all the dictatorships, there’s such a non-understanding of what human beings are. I mean, if you believe in the Bible, you have the story of Adam and Eve and God tells them, “Do whatever you want. The only thing you shouldn’t do is eat the apple.” What do they do the first thing? They eat the apple. So if you know a little bit the psychology of human beings, you have to understand that if you say something you should not do, then everybody wants to do it.

The unattainable Irane (Golshifteh Farahani).Sony Pictures Classics

The unattainable Irane (Golshifteh Farahani).Sony Pictures Classics

MJ: I’ll need to remember that with my kids.

MS: [Laughs.]

MJ: So would you be in trouble if you tried to go back to Iran?

MS: I know that I can go there, but I’m not sure if I can come back. This is the problem. And that’s why I don’t go. I have not gone for 12 years now.

MJ: For the Persepolis film, you stuck pretty close to the book. With the new one, you adapted your graphic novel into a live-action film. Contrast the two experiences.

MS: With animation, if something does not fit, you always have the time to change it. When you make a live-action movie—I didn’t have a big studio behind me—so when my 46 days of shooting were over, they were over forever. You have seen the movie: It’s like a puzzle; there is not one scene you can miss, because if you don’t have it then the whole construction doesn’t work. So you had a big, big pressure. And at the same time, it is like living three years of life in three months. Everything is extremely intense. And every feeling you have is exaggerated by 12. It’s really living extremely densely a moment of life. So the experiences are very different. The question is to know if you are a marathon man or you are a 100-meter sprinter.

MJ: This was your first time directing real actors on set—and you had some well-known actors like Isabella Rosellini and Mathieu Amalric. Was that intimidating?

MS: Not really, because they were very nice people. I called, for example, Isabella Rosellini, whom I didn’t know at all, and she told me right away, “I’m in.” And I say, “Well, maybe you want to read the script?” And she said, “I never choose the film because of the script, I just like to work with some people and I like to work with you, so I am in.”

MJ: And she hadn’t even met you?

MS: No, but she knew my work. I called Mathieu Amalric. I had met him like two times before, and I didn’t know that he was in love with the book Chicken with Plums. I told him, “I want you to play this role.” And he told me, “How do you want me to refuse a project like that?” So it went very well. Maybe it would not be the same if I didn’t have these actors, but, you know, you smell people. I saw other actors, and when I feel that they are difficult, I don’t feel like working with them. Because making a film should be a joy. The things that I do today are the things I did as a child. When I was a child, either I was drawing or I was taking all the kids off my street and I wanted to make shows—I was all the time making! The only thing is, now I know how to do it better, and now they give me money for it.

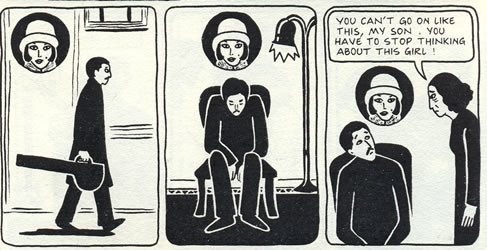

Nasser-Ali dreams of Irane in the graphic novel version. Knopf DoubledayMJ: You must be very happy!

Nasser-Ali dreams of Irane in the graphic novel version. Knopf DoubledayMJ: You must be very happy!

MS: Very happy.

MJ: Excellent. So what filmmakers most inspired you in the making of this film?

MS: For the aesthetic, we watched lots of the ’50s movies of [Michael] Powell and [Emeric] Pressburger. They made The Red Shoes and The Black Narcissus. Because it’s incredible—the images of these films is just unreal. I like the melodrama of Douglas Sirk. But in Douglas Sirk movies, you never have a moment [as in Chicken With Plums] when the father wants to give the last word and the kid farts, you know?

MJ: That was funny. It could easily have come straight out of Persepolis.

MS: Exactly, because this kind of thing actually happens in life. You never have these moments that, you know, are always perfect. Always something happens.

MJ: Back in 2007, you told this magazine that you had sexual fantasies about Darth Vader. In this film, the Angel of Death makes a memorable appearance—

MS: Well, it’s the same thing.

MJ: What attracts you to these dark characters?

MS: As a child reading comics I was always bored by Superman with his curled hair, because he was all nice and tidy. I was in love with Batman because he was full of hate and he was in his tower in Gotham City and he had this Batmobile and he had some kind of bizarre relationship with Robin but nobody would say it. I have my dark side. You have your dark side. From the second that we have a brain, there are things that are not right—we are human beings with all these illusions and complexes and everything. That’s attractive to me. So the sexual dream about Darth Vader and the Angel of Death is not so far away. I like these characters because they resemble what a human being is. The really, really nice guy? I’m sure they’re hiding some perversity somewhere. You cannot be completely nice. It’s impossible. Who is it? Who is the perfect guy? Show him to me! It doesn’t exist. And thank god.

MJ: Changing gears, you’re certainly not the first writer to explore the plight of the artist in society—Kafka comes to mind. In what ways would you say you relate to your protagonist Nasser-Ali?

MS: Very much so. When I described him, I didn’t have this automatic, unconscious censorship that I make to myself. As soon as I draw a female, I know everybody is going to relate it to me. So even unconsciously there are things that I won’t say. When I create a male character, they wouldn’t know it’s me, so I could just say much more. And yeah, just like him, I’m extremely unbearable. You know, I’m narcissistic and at the same time I’m very charming—I think.

MJ: He really struggles with the strictures of society. Et tu?

MS: There is a problem in many societies that I don’t quite understand what is this problem. I remember many years ago for the Super Bowl, Janet Jackson, suddenly her breast jumped out. And everybody went, you know, Wow! And I was like: What is the problem with the nipple? It’s just a nipple. It’s round, it’s cute, it doesn’t bite, it’s warm, it’s soft. All of us have eaten the nipple of our mothers, so all of us have seen nipples. What is the big deal? At the same time they were bombing Iraq and people they were dying. No problem. Nobody was furious against it. But then just one breast? When you don’t make any harm to others, I don’t understand why it should be restricted. What the hell is the problem? So yes, I have that. Forever! Maria de Medeiros and Mathieu Amalric as the miserable couple, Faringuisse and Nasser-Ali. Sony Pictures Classics

Maria de Medeiros and Mathieu Amalric as the miserable couple, Faringuisse and Nasser-Ali. Sony Pictures Classics

MJ: So, I couldn’t help but feel sorry for Nasser-Ali’s wife, who is also unbearable, but mainly because she loves him and he loathes her.

MS: She has missed his love. He meets another woman, but he misses her too. Everybody is missing everybody. But, you know, this is also in the ’30s. Do you think a girl from a bourgeois family could go to say to her father, “I’m going to marry this musician,” and everybody would applaud you? It was not like that. But this film is also saying that we have only this life. He misses his life first by missing his love, then by missing his wife. Of course you feel sorry for her. I felt so sorry for her! And that’s why I wanted Maria de Medeiros to do it, because she’s such a graceful actress, and she plays this ugly, harsh woman, and little by little you understand that no, she is beautiful, and at the end you feel sorry for her. That is what I wanted.

MJ: The notion of star-crossed lovers is an age-old theme. You could go either the tragedy route or the fairy tale. You chose tragedy. Do you think our quest for romantic love is futile?

MS: I think that no subject is more serious than the subject of love. And I think that if we are really honest to ourselves, we cannot survive a broken heart. It’s extremely difficult. We tell ourselves stories: He was not as good as I thought. He was this, he was that, nah nah nah. But in reality, when our heart is broken, there’s nothing to do. And Nasser-Ali is honest. At one point, he is like, “Okay, I will die because of my love.” So it’s a happy end. And, you know, love is the only subject in front of which we are all in equality. We always say we are equal in front of death, but when you are rich, for example, and you have everybody taking care of you, I think that you suffer much less. It must be much more painful to die when you are poor than when you are rich. But when your heart is broken, you can be rich, poor, whatever—a broken heart, we are all equal in front of it. And I think there is no subject more serious.