Beyza Durmuş

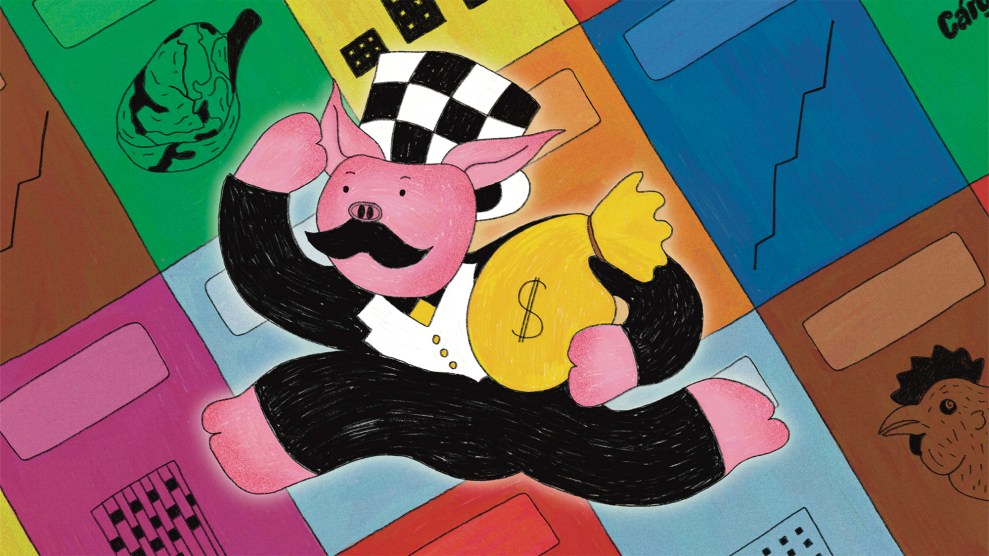

The bacon in your BLT now costs nearly twice as much as it did 15 years ago, but inflation is only part of the reason. Broadly speaking, food and drink prices only grew by about 50 percent during that time. So, what’s up with the meat?

The answer may have to do with Agri Stats, a small data venture based in Indiana. In 2023, the Department of Justice, backed by a coalition of state attorneys general, sued the company, accusing it of violating the Sherman Antitrust Act by enabling the exchange of anticompetitive information, leading to artificially high meat prices. (Agri Stats has denied wrongdoing.)

The exchange works like this: For two decades, Agri Stats has been collecting metrics from the country’s largest meat processors on all kinds of things—pork and chicken-thigh inventories, production speeds, meatpacking wages. It analyzes the intel and creates reports that it distributes back to its members—dominant players that can afford to pay millions for a subscription—which use the info to set prices. Agri Stats had been running this exchange within Federal Trade Commission antitrust “safety zones” guidelines that permitted “reasonable” sharing of information between rivals in a given sector.

Those guidelines were rescinded in 2023, which opened the door for the DOJ to claim the information exchanges harm competition, in part because Agri Stats focuses on boosting the industry’s profitability—in some cases, it allegedly encouraged companies to restrict output, thereby reducing supply, and jack up their prices. (Agri Stats argues that it helps protein producers identify ways to keep production costs, and prices, low.)

“Consumers have very little choice for where to purchase meat, and farmers have very little choice for where to sell it.”

Agri Stats isn’t solely to blame, of course. Just four conglomerates—JBS Foods, Tyson Foods, Cargill, and Marfrig—control up to 85 percent of the meat industry’s supply chain. For many years, Agri Stats’ member firms accounted for more than 90 percent of broiler chicken, 80 percent of pork, and 90 percent of turkey sold in the United States. As long as the giants all raised their prices, the DOJ argues, there was little competitive risk in doing so.

This is not the first time the big meatpackers have faced scrutiny for monopolistic behavior. In the early 20th century, a federal investigation concluded that the era’s five biggest players were colluding, which threatened competition. The resulting Packers and Stockyards Act of 1921 aimed to end such behavior by prohibiting unfair pricing, manipulation of supply chains, and other noncompetitive activities.

But in the 1980s, a shift in the courts and the election of President Ronald Reagan led the DOJ to abandon aspects of antitrust enforcement as the new administration embraced conservative economist Milton Friedman’s belief that markets will self-correct. A flurry of mergers followed. And tech advancements allowed large slaughterhouses to process meat faster and more cheaply than the smaller plants.

Consolidation, combined with sophisticated data tools, has created an environment ripe for manipulation, according to antitrust scholar Austin Frerick, author of the 2024 book Barons: Money, Power, and the Corruption of America’s Food Industry. As companies amass power, he told me, “data brokers become more effective,” thereby encouraging more consolidation: “It’s a system that reinforces itself.

“This isn’t rocket science—it’s really just a question of political courage.”

As a result, “consumers have very little choice for where to purchase meat, and farmers have very little choice for where to sell it,” says Jennifer Curtis, co-founder of North Carolina’s Firsthand Foods, which buys animals from local farmers, coordinates processing, and sells the meat to restaurants and grocers. With the right support, regional supply chains could loosen Big Meat’s grip on the market. Curtis says her state is making headway on boosting the little guys: A recent program, for instance, tapped into Covid relief funds to provide grants for small-scale meat processors that help them serve more farmers and get more of their products to market.

Reining in Big Meat will require bolder federal action. On the campaign trail, Kamala Harris proposed a federal ban on price gouging that could provide a legal framework to challenge market manipulators. But the most important move, Frerick says, is simply to en-force existing laws: “In the meat industry, we already did this all a century ago. This isn’t rocket science—it’s really just a question of political courage.”