Party of One Studio

Back in 2010, then–first lady Michelle Obama launched a nefarious scheme to turn school cafeterias into liberal indoctrination zones. Or at least that’s how Obama’s right-wing opponents portrayed the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act, a law she spearheaded that gave the National School Lunch Program its first nutritional update in more than 15 years. Her treachery included requirements for more fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, and limits on calories in meals. “Here’s Michelle Obama trying to take over the school lunch program,” Rush Limbaugh warned his radio audience. Media outlets flaunted photos of kids dumping their lunches into the trash, supposedly taken after the reforms went into effect. Rep. Steve King (R-Iowa) sponsored a bill to nullify the nutrition rules in 2012, decrying what he called a “misguided nanny state” that “would put every child on a diet.”

The nanny-state rhetoric got attention. Less attention-getting was the fact that Obama’s critics were attacking improvements to a crucial anti-poverty program. Of the nearly 30 million kids who eat school lunches every day, 20 million qualify for free lunch—and another 1.8 million receive it at a reduced price. Altogether, these kids rely on school meals for nearly half their daily calories and 40 percent of their vegetable intake, making the program a “safety net for low-income children,” a 2016 study from Baylor University researchers found.

Hear more about school-cafeteria politics—including another Michele Obama reform that allows high-poverty schools offer universal free lunch—in the latest episode of Bite podcast:

For decades, companies like Tyson Foods and Domino’s have found a prominent market in school cafeterias, wooing administrators with entrees like chicken nuggets and pizza, which please kids, require minimal preparation, and don’t strain tight budgets. The Obama rules didn’t overhaul this paradigm, says Bettina Elias Siegel, author of the forthcoming book Kid Food, but “overall there’s no question that school meals got healthier.”

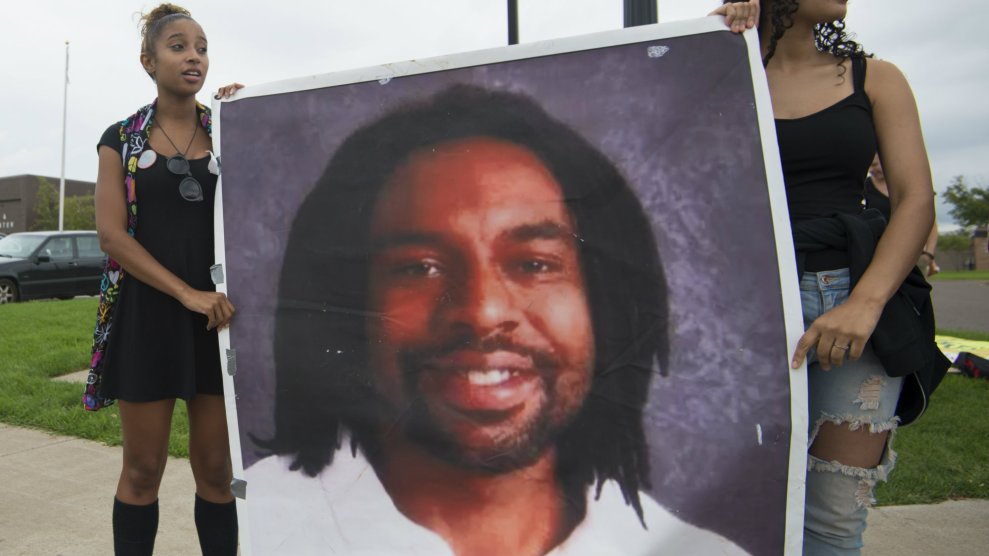

King’s school lunch bill stalled in Congress, but the right-wing zeal for reversing Obama’s agenda stayed on a slow boil. Then, in 2016, a man obsessed with taco bowls and Big Macs claimed the presidency. Just before Donald Trump took office, the far-right House Freedom Caucus released a hit list of more than 300 rules and regulations that urgently needed to be revoked or examined in his first 100 days. First on the list: the Obama lunch reforms.

In May 2017, Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue appeared at an elementary school in Virginia, vowing to “Make School Meals Great Again.” Echoing Freedom Caucus talking points, Perdue announced that “if kids aren’t eating the food, and it’s ending up in the trash, they aren’t getting any nutrition.” He also asserted that procuring whole grain foods like pasta was imposing “problematic” costs on cafeterias. For good measure, he added that “I wouldn’t be as big as I am today without chocolate milk.”

For all the bluster, Perdue’s new rules, put into law in February 2019, represented a fairly modest rollback. The Obama guidelines stipulated that starches like pasta and buns must contain at least 50 percent whole grains and that chocolate milk could contain no fat. Perdue cut the grain requirement in half and allowed flavored 1 percent milk. He weakened a mandate to cut salt levels, but he left calorie limits and requirements for more fruit and vegetables intact.

Meanwhile, researchers contracted by his own department were studying the impact of the Obama-era reforms. The results, quietly released in April, demonstrate that the conservative backlash was based on nonsense. The USDA study compared school years before and after the Obama reforms. It turns out that serving healthier food did not result in significantly higher costs for cafeterias or mean more food going into the garbage. The reforms did, however, result in healthier lunches—more whole grains, greens, and beans, as well as fewer “empty calories” (added sugar and solid fats) and less sodium. And maybe most importantly, the cafeterias that delivered higher healthy-food scores also had significantly higher rates of students choosing to eat the lunches. That same month, attorneys general from six states and the District of Columbia sued the USDA, charging that the rollbacks were made without public input and were “not based on tested nutritional research.”

Cafeteria administrators haven’t had much appetite for Perdue’s alterations, either. Anneliese Tanner is the food services director for the Austin, Texas, school district, where more than half of all students qualify for free or reduced-price lunch. Obama-era reforms, she says, prompted her cafeterias to move to whole grains, and “the kids have gotten used to them, more or less.” For Tanner, school lunches are not a front in a culture war, but an effective way to nourish kids who might not otherwise have access to nutritious food. “Would they eat more white flour tortillas and white pasta? Probably,” she says. “Is that our focus? No. We’re going to stay the course and focus on our kids’ health.”