Irrigation pipes on Southern California farmland. <a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-191969807/stock-photo-the-water-irrigation-pipes-in-the-dry-southern-california-farmland.html?src=pd-same_artist-191969795-JqNUbW07QeUElABFL5pa-g-4">Eddie J. Rodriquez</a>/Shutterstock

Late-summer 2014 has brought uncomfortable news for residents of the US Southwest—and I’m not talking about 109-degree heat in population centers like Phoenix.

A new study by Cornell University, the University of Arizona, and the US Geological Survey researchers looked at the deep historical record (tree rings, etc.) and the latest climate change models to estimate the likelihood of major droughts in the Southwest over the next century. The results are as soothing as a thick wool sweater on a midsummer desert hike.

The researchers concluded that odds of a decadelong drought are “at least 80 percent.” The chances of a “megadrought,” one lasting 35 or more years, stands at somewhere between 20 percent and 50 percent, depending on how severe climate change turns out to be. And the prospects for an “unprecedented 50-year megadrought”—one “worse than anything seen during the last 2000 years”—checks in at a nontrivial 5 to 10 percent.

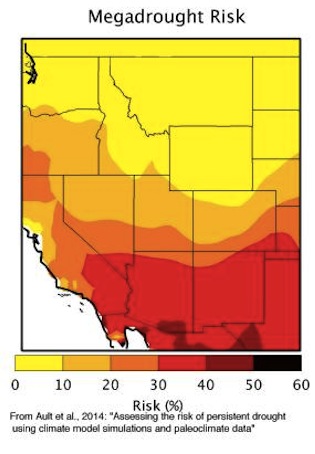

To the right there’s a map, pulled from the study, showing that the swath of land in question and its risk of a 35-year drought. It extends from Southern California clear to West Texas, encompassing population centers like San Diego, Phoenix, Tucson, and Albuquerque, along with a large chunk of the troubled US-Mexico border. (Note that in northern Mexico, drought prospects are even higher.)

This (paradoxically) chilling assessment comes on the heels of another study (study; my summary), this one released in early August by University of California-Irvine and NASA researchers, on the Colorado River, the lifeblood of a vast chunk of the Southwest. As many as 40 million people rely on the Colorado for drinking water, including residents of Las Vegas, Los Angeles, Phoenix, Tucson, and San Diego. It also irrigates the highly productive winter farms of California’s Imperial Valley and Arizona’s Yuma County, which produce upwards of 80 percent of the nation’s winter vegetables.

The researchers analyzed satellite measurements of the Earth’s mass and found that the region’s aquifers had undergone a much-larger-than-expected drawdown over the past decade—the region’s farms and municipalities responded to drought-reduced flows from the Colorado River by dropping wells and tapping almost 53 million acre-feet of underground water between December 2004 and November 2013—equal to about 1.5 full Lake Meads drained off in just nine years, a rate the study’s lead researcher, Jay Famiglietti, calls “alarming.”

Considering how much of the Colorado River Basin, which encompasses swaths of Utah, Colorado, California, Arizona, and New Mexico, are desert, it’s probably not wise to rapidly drain aquifers, since there’s little prospect that they’ll refill anytime soon. And when you consider that that the region faces high odds of a coming megadrought, the results are even more frightening. (Just before Labor Day, over fierce opposition from farm interests, the California Legislature passed legislation that would regulate groundwater pumping—something that has never been done on a statewide basis in California before. Gov. Jerry Brown is expected to sign it into law.)

Yet another study, this one released in mid-August by researchers from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography and the US Geological Survey and covered by my colleague Julia Lurie here, found that the drought now gripping most of California has been so severe that it has caused the state’s mountain ranges to rise by as much as a half inch since 2013 alone. That’s because water, in the form of snow on mountain peaks and flow in streams, weighs down on the tectonic plate upon which the mountains rest. When it’s not replaced, as happens during a drought, the plate rises “like an uncoiled spring,” as the Scripps Institution of Oceanography put it in a press release. Scripps added, thankfully, that the “uplift has virtually no effect on the San Andreas fault and therefore does not increase the risk of earthquakes.” Whew.

But the “uplift effect” doesn’t just happen in mountain areas. The researchers estimate that across the West, loss of surface water has caused the land to rise 0.15 of an inch since 2013. Such a tangible change over so short a time illustrates the “the dire hydrological state of the West,” the Scripps press release states.