Germ: Shutterstock; Bull: Shutterstock; Hat: Shutterstock

Nearly 80 percent of antibiotics consumed in the United States go to livestock farms. Meanwhile, antibiotic-resistant pathogens affecting people are on the rise. Is there a connection here? No need for alarm, insists the National Pork Producers Council. Existing regulations “provide adequate safeguards against antibiotic resistance,” the group insists on its site. It even enlists the Centers for Disease Control in its effort to show that “animal antibiotic use is safe for everyone,” claiming that the CDC has found “no proven link to antibiotic treatment failure in humans due to antibiotic use in animals.”

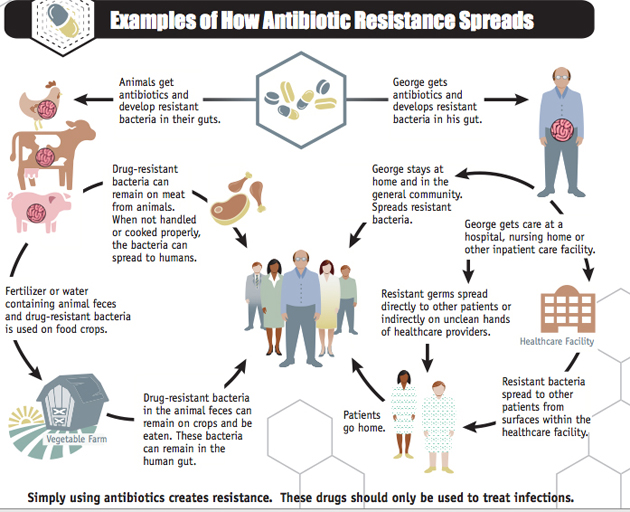

So move along, nothing to see here, right? Not so fast. On Monday, the CDC came out with a new report called “Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013,” available here. And far from exonerating the meat industry and its voracious appetite for drugs, the report spotlights it as a driver of resistance. Check out the left side of this infographic drawn from the report:

Note the text on the bottom: “These drugs should be only used to treat infections.” Compare that to the National Pork Producers Council’s much more expansive conception of proper uses of antibiotics in livestock facilities: “treatment of illness, prevention of disease, control of disease, and nutritional efficiency of animals.” Dosing animals with daily hits of antibiotics to prevent disease only makes sense, of course, if you’re keeping animals on an industrial scale.

The CDC report lays out a couple of specific pathogens whose spread among people is driven by farm practices. Drug-resistant campylobacter causes 310,000 infections per year, resulting in 28 deaths, the report states. The agency’s recommendations for reducing those numbers is blunt:

• Avoiding inappropriate antibiotic use in food animals.

• Tracking antibiotic use in different types of food animals.

• Stopping spread of Campylobacter among animals on farms.

• Improving food production and processing to reduce contamination.

• Educating consumers and food workers about safe food handling

practices.

Then there’s drug-resistant salmonella, which infects 100,000 people each year and kills 38, CDC reports. The agency lists a similar set of regulations—including “Avoiding inappropriate antibiotic use in food animals”—for reversing the rising trend of resistance in salmonella.

Finally, there’s Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, or MRSA, which racks up 80,461 “severe” cases per year and kills a mind-numbing 11,285 people annually. The CDC report doesn’t link MRSA to livestock production, but it does note that the number of cases of MRSA caught during hospital stays has plunged in recent years, while “rates of MRSA infections have increased rapidly among the general population (people who have not recently received care in a healthcare setting).”

Why are so many people coming down with MRSA who have not had recent contact with hospitals? Increasing evidence points to factory-scale hog facilities as a source. In a recent study, a team of researchers led by University of Iowa’s Tara Smith found MRSA in 8.5 percent of pigs on conventional farms and no pigs on antibiotic-free farms. Meanwhile, a study just released by the journal JAMA Internal Medicine found that people who live near hog farms or places where hog manure is applied as fertilizer have a much greater risk of contracting MRSA. Former Mother Jones writer Sarah Zhang summed up the study like this for Nature:

The team analyzed cases of two different types of MRSA — community-associated MRSA (CA-MRSA), which affected 1,539 patients, and health-care-associated MRSA (HA-MRSA), which affected 1,335 patients. (The two categories refer to where patients acquire the infection as well as the bacteria’s genetic lineages, but the distinction has grown fuzzier as more patients bring MRSA in and out of the hospital.) Then the researchers examined whether infected people lived near pig farms or agricultural land where pig manure was spread. They found that people who had the highest exposure to manure—calculated on the basis of how close they lived to farms, how large the farms were and how much manure was used—were 38% more likely to get CA-MRSA and 30% more likely to get HA-MRSA.

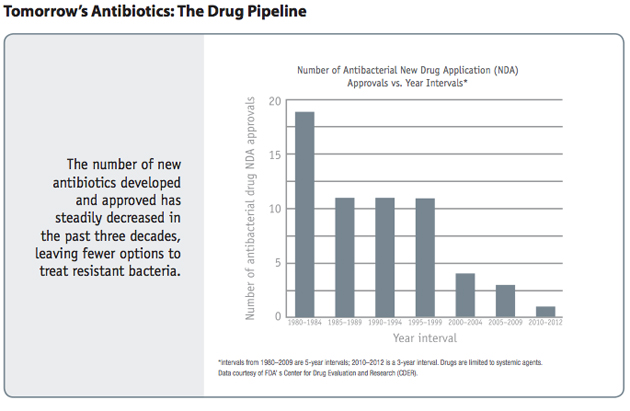

In short, the meat industry’s protestations aside, livestock production is emerging as a vital engine for the rising threat of antibiotic resistance. Perhaps the scariest chart in the whole report is this one—showing that once we generate pathogens that can withstand all the antibiotics currently on the market, there are very few new antibiotics on the horizon that can fill the breach—the pharma industry just isn’t investing in R&D for new ones.

Last year, the Food and Drug Administration rolled out proposed new rules for antibiotic uses on farms. At the time I found them wanting, because they include a massive loophole: They would phase out growth promotion as a legitimate use for antibiotics, but still accept disease prevention as a worthy reason for feeding them to animals. As I wrote at the time, “The industry can simply claim it’s using antibiotics preventively and go on about its business—continuing to reap the benefits of growth promotion and continuing to menace public health by breeding resistance.” To repeat the CDC’s phrase from its new report, “These drugs should be only used to treat infections.” Worse, the FDA’s new rules would be purely voluntary, relying on the pharma and meat industries to self-regulate.

Nearly a year and a half later, the FDA still hasn’t moved to initiate even that timid step in the right direction. Perhaps the CDC’s blunt reckoning will provide sufficient motivation.