<a href="http://nah.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C4%AAxiptli:Ako_fish_market.jpg">Gregg Tit con ! from Tel Aviv</a>/Wikipedia

Trust salmon, maybe red snapper, but not tuna. These are the lessons a nervous seafood eater could glean from a new study by the marine-life advocacy group Oceana. A whopping 87 percent of red snapper and 84 percent of “white” tuna tested was found to be mislabeled, the study found.*

But only seven percent of salmon—one of the most commonly consumed fish in the US—was mislabeled, making it a somewhat bright spot in a sketchy fish market.

More than 300 volunteers served as food detectives for the study, purchasing more than 1,200 samples of seafood from 674 restaurants, sushi bars, and grocery stores in in major cities between 2010 and 2012. Oceana then DNA-tested the fish to catch imposters.

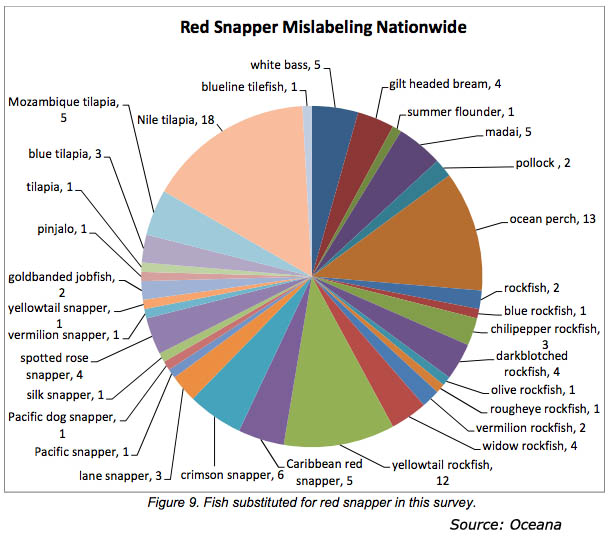

So what are you eating, really? For example: The report found a hodgepodge of fish masquerading as snapper, some more palatable than others:

The best chances of finding actual red snapper were in Miami, New York, and in Boston, where several samples of red snapper ironically turned up in a grocery store mislabeled as a different fish. In samples from out west, including San Francisco, Portland, Seattle and Los Angeles, all of the red snapper was mislabeled, according to USDA standards.

As Oceana notes, red-snapper mislabeling (and fish mislabeling in general) is nothing new: Studies have been finding similar trends since the ’90s. The reason: Red snapper became so popular in the 1970s and 1980s that the government put restrictions on catching it to prevent overfishing, so demand has remained high while the supply is kept relatively low.

Tuna marketed as “white tuna” was another big culprit in Oceana’s study: 94 percent of all white tuna samples were actually escolar, also known as “the ex-lax fish,” which is banned in Italy and Japan.

Oceana notes that “it is difficult to identify if fraud is occurring on the boat, during processing, at the retail counter or somewhere along the way.” In other words, it’s nearly impossible to figure out who is responsible for the mislabeling, especially in an increasingly global fish market.

Correction: An earlier version of this article stated that 94 percent of canned tuna was mislabeled. 94 percent of white tuna in the study was mislabeled. The sentence has since been fixed.